Visite Critique Donaueschingen: Nika Schmitt

The following text was written in the context of the visite critique during the Next Generation workshop at the Donaueschinger Musiktage 2025.

On Abweichungsversuche by Nika Schmitt

A text by Julia Krabes

Nika Schmitt filled the Orangerie’s enfilade on the upper floor with what the program called an “electro-mechanical chain reaction“. On paper that sounds almost theatrical. In practise, Abweichungsversuche was closer to an experiment that had started before anyone arrived and would probably continue after they left — part kinetic study, part stubborn noise.

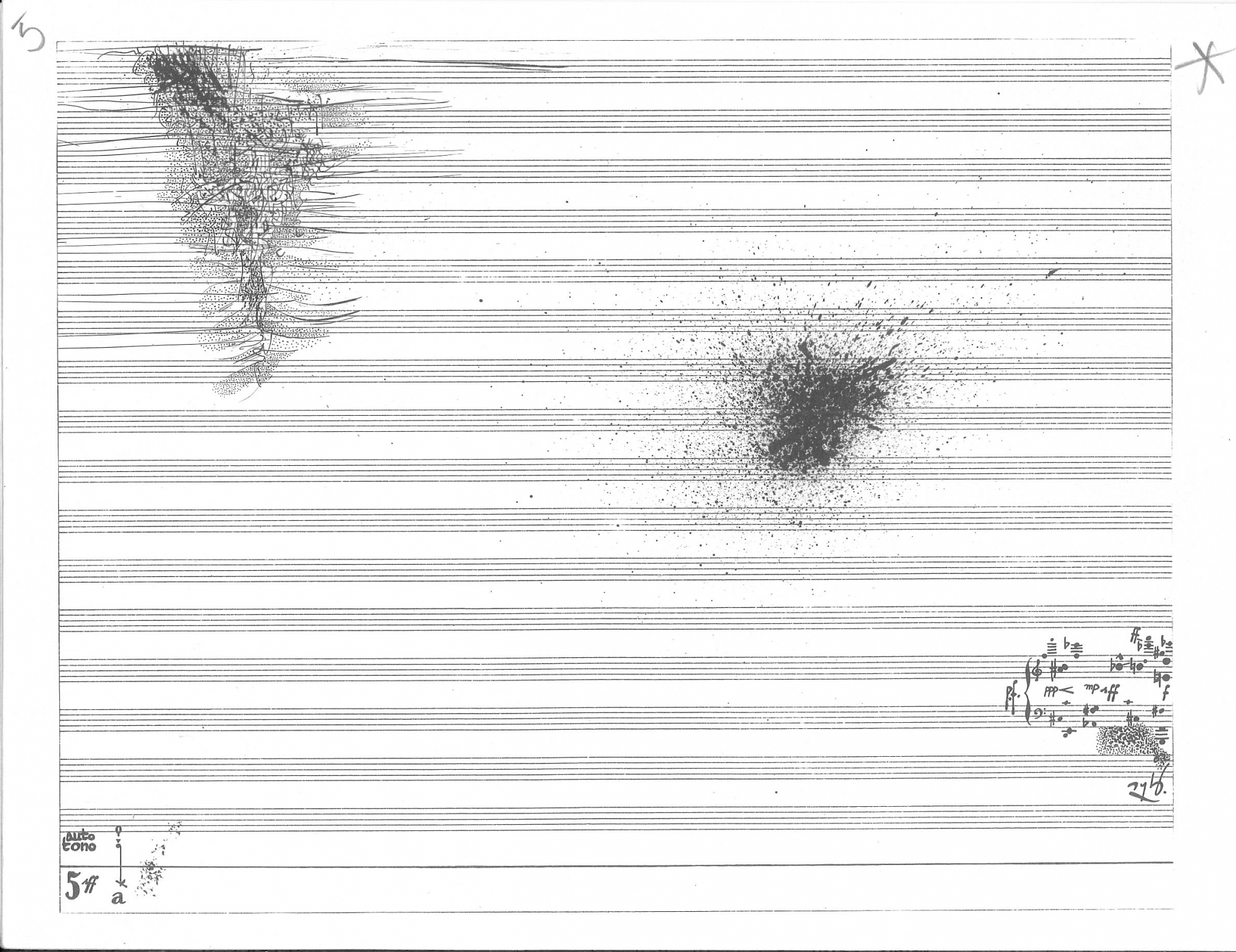

Two to three large metal plates hung in each of the connected rooms, each suspended by one thread of wire on each side and attended by a microphone pointing at it like a question mark. Smaller plates rested on the floor or were attached to the wall with no discernible logic. In the artist talk afterwards, Schmitt was clear about at least, one thing: the small plates had no meaning.

The sound was not so much composed as endured. A high, uneven vibration ran through the rooms, textured with harsh overtones that recalled a drill whose motor has begun to dull. Every few minutes, a collective rumble dragged the system briefly into order before it slipped apart again. It was less music than fatigue in audible form — a system rehearsing its own decline.

The rooms were open to one another, separated only by shallow thresholds. Crossing from one to the next meant stepping through invisible membranes of sound – thicker near the plates, thinner in the gaps. Standing close, the vibration turned tactile, at distance it dissolved into the air. The work’s real movement was not sonic but spatial: it made listening a kind of slow erosion, where attention corroded the longer one lingered.

The openness of the installation — no limits, no fixed beginning or end — meant the work existed in a constant state of entropy. Visitors came and went, exchanging, photographing, almost wanting to touch the metal. The Orangerie became a study in collective decay, not of objects but of focus: How long can a shared act of listening survive before it collapses back into ordinary noise?

Somewhere behind the hum were traces of another “world“. The recordings, Schmitt mentioned, were made elsewhere — at a previous place the installation took place in where there was a construction at that time. That processed into this network of feedback loops. This knowledge shifted the works tone; the metallic grind began to resemble labour, the sharp pulses like a mechanical breath. Occasionally a faint conversation leaked through, the ghost of work embedded in art. The corridor seemed to hold two kinds of time at once — the clean stillness of an exhibition space and the rough, ongoing duration of the recording. The sounds moved through the rooms like traces of work still in progress. Each echo carried a small difference, as if the past version of the sound never quite aligned with the present one. Listening became a slow recognition of how things fall slightly out of sync over time.

The audience also shaped the piece because there was no limit to how many people could enter at the same time, the atmosphere changed constantly. When the corridor filled up, the air became dense, the metallic tones duller, and the low rumbles seemed to have spread unevenly. When only a few visitors were present, the sound felt sharper, more directed. In both cases, the installation seemed to adapt to the bodies in the space. It was not only a technical system; it was also social, testing how much focus or distraction a collective experience could sustain.

In that instability, there was something very fragile. The work never demanded silence, but it also never competed for attention. It just kept going, repeating its own small gestures, like a mechanism running until it forgets why it started. Schmitt’s refusal to provide interpretation in the artist talk felt consistent. Rather than guiding the audience she left the installation to explain itself — or not. That restraint might have seemed detached, but it also respected the work’s uncertainty.

In the end, Abweichungsversuche was less abut the beauty of sound than about its erosion. It shows what happens when control starts to fade and repetition turns into fatigue. The piece did not collapse, it slowed, drifted, persisted. Maybe that was its real meaning: decay not as a failure, but as a way of continuing.