THREE PARADOXES OF CONTEMPORARY MUSIC

The notion of music installations is an oxymoron. It combines ideas that normally exclude each other: music and installation; that is, a performative art of sonic time structures and a post-medium art of spatial assemblages. The artworks shown under this title in Nuremberg in July 2022 tried to overcome this opposition. They were driven by a desire to combine artforms that seem to contradict each other. This desire led them into the field of paradoxes. In what follows, I will identify three of these paradoxes: the paradox of creating situations, the paradox of static sound and the paradox of a musical performance art. These paradoxes characterize many contemporary productions in music and art in general. I would like to argue that this tendency is more than a mere fashion; rather, the fact that contemporary art is driven by paradoxical intentions and desires stems from the basic structure of artistic production. Thus, before I describe the three paradoxes, I will try to clarify this underlying connection between artistic production and paradoxical intentions.

I Art and the paradox

In what follows, I will presuppose a certain conception of art which establishes a necessary relation between artworks and aesthetic judgment. Artworks are artefacts that are aesthetically convincing; the aesthetic judgment is primarily the judgment by which one claims something to be art. In contrast to scientific assertions and theories, artworks are not primarily supposed to show what is the case; and in contrast to the actions and deeds of moral subjects, artworks are not primarily supposed to realize something good or useful. There is no doubt that artworks are related to facts and values in manifold ways, but they are not reducible to these relations. An artwork sets out to be convincing in another way.

The aesthetic or art-critical judgment differs from a statement of fact or an evaluation by its very structure: it does not identify conceptually what it judges. To identify here means to recognize what kind of thing the thing in question is. The art critic judges an object without presupposing what kind of thing the object is: she does not apply the concept of the thing as the measure of her critical judgment. An artwork is appreciated independently from its being an object of a certain kind; it is convincing even though – and to a certain extend because – one does not finish wondering what exactly it is.

If this is true, then artistic production faces a particular difficulty. For its task is to produce things of which one does not know what they are. Artistic production is the production of something unidentified. However, it is obvious that the artist must know what they are doing. Their efforts and operations are necessarily guided by plans, concepts and intentions which they must have identified if they want to follow them. So how is it possible that the artistic production is led by conceptually identified intentions and yet produces something that cannot be fully grasped?

The performance piece Rewriting and Science Fiction by Jonathan Burrows and Matteo Fargion performed in Nuremberg draws exactly on this problem. During the performance, Burrows reads out texts written on cards by enacting a rigidly but incomprehensibly structured set of gestures. The text consists of preparatory notes and work intentions for a performance piece that turn around the failure and vanity of artistic efforts, the glaring discrepancy between the seriousness in act of producing art and the strange senselessness in its product.

One possible answer to the problem of artistic production is the paradox. The gap between the identified intention of production and the non-identified product can succeed if the conceptual intention which governs the working process is a paradoxical one. In this way, the old idea of artists longing for the impossible can be freed from the obscurities of the cult of genius and reveal a true kernel: the impossibility that guides artistic production is the paradoxical intention to generate something of which one does not know what it is.

But what is a paradox? A first approximation could be: a paradox is intelligible nonsense. A paradoxical idea is one which seems, at first sight, to be perfectly understandable, but which upon reflection reveals itself to be contradictory. The idea finishes in disintegration, it ends up negating itself. This kind of idea is quite common. An example one often encounters is the well-intentioned remark: don’t follow any advice! At first, this counsel seems perfectly clear. Upon reflection one realizes that the advice not to follow any advice leads into a contradictory series of thoughts: if you follow the advice not to follow any advice you end up going against it. But if you don’t follow it in the first place, you actually do follow it and thereby again contravene it; and so on. The intention of artistic production might have a similar structure: paradoxical, self-negating conceptions of what has to be done in order to generate an artwork. That’s why the idea that contemporary art is driven by paradoxes does not necessarily imply a refusal of such intentions: they could be legitimate means to produce art. The art critical discourse, however, would be well advised to see clearly that the intentions are intelligible nonsense.

II The paradox of creating situations

Such a paradoxical intention lies at the very heart of the artistic current of situationism. Situationist strategies have recently become influential again after a short-lived existence in the 1950s and 60s. Their leading artistic intention is to create art as situations and encounters rather than as objects and spectacles. The historical background of this strategy is the diagnosis of capitalist reification. The capitalist social formation generates a form of subjectivity to which social and intersubjective relations appear to be properties and relations of things. The paradigm of reification is the commodity which appears to possess its value as a property whereas, in fact, its value is the outcome of the social organization of production and distribution. The same goes for art – says the situationist. In art as well, things and spectacles are taken to be the bearers of some mysterious quality of artfulness whereas, in fact, art is nothing but a social, intersubjective relation. As long as artistic production is conceived as a production of things and events, art continues to be reified. The situationist negates this reification of art into art objects and artistic performances, into commodities and spectacles, by conceiving artistic production as the generation of social situations and inter-subjective encounters.

But how does one create a situation? How does one generate an encounter? Two strategies suggest themselves. First, the artist can create an indeterminate and open frame in which situations and encounters between the participants of the artistic gathering might happen. The idea of eating and conversing with each other at exhibitions has, for example, become a widespread way of doing situationist art today. In Nuremberg, the project Hausen by Leo Hofmann and Benjamin van Bebber were partly inspired by this idea: Over the course of four days, they invited the public to join them in a town house for having tea, dinner and drinks, and occasionally for attending a performance. If the diagnosis of reification is true, however, this will not do the work. For the participants of such events are subjects that are formed and deformed by the capitalist society. They are subjects who reify each other and themselves. If you leave it to these subjects to make encounters and generate situations of real intersubjectivity, they will immediately reproduce their reifying and reified modes of thinking and behaving within the framework of art.

This problem leads some artists to opt for a second strategy. This consists in imposing certain norms of behaviour – like the rules of a game – upon the participants of the art situation. Only in this way (so goes the reasoning) can the participants be liberated from their normal, reifying behaviour and be pushed into a real situation of encounter between human beings. The highly choreographed yet participative work DREAMS* by Heinrich Horwitz and the Decoder Ensemble that was shown in Nuremberg somehow opted for this strategy. But again, there is a problem. For those who participate in such pre-structured interactions by submitting themselves under given rules can precisely not understand their behaviour as the manifestation of self-determined subjectivity. The participants appear – to others and to themselves – as variables in a heteronomous succession of events, as functions of a game they do not determine. In short, they are themselves reified by the art situation that appears to them as a thing-like mechanism to which they must adapt.

The paradox of creating situations can be put as follows: the situationist’s intention to ban reification from art generates in itself ever new forms of reification. This strange formulation expresses the simple insight that situations and encounters – in the emphatic sense – cannot be created: they can only happen. The paradoxical intention of situationism is akin to the plan to bump into someone or the wish to be surprised. Whether or not this kind of intention might produce convincing artworks depends on the consequence with which the nonsensical nature of this artistic endeavor is thought through.

III The paradox of static sound

The expression music installation is a modification of the established notion of sound installation. The latter notion designates artworks that organize sound spatially instead of presenting sound as something temporal, that is, a musical performance. It goes without saying that installations, just like every other spatial object, only exist in time and that their reception by the visitor, too, happens as a temporal occurrence. This is not the point. A sound installation is usually taken to be distinct from a work of music insofar as it is indifferent to its necessarily temporal existence and reception.

The ontological distinction between a state and an event might clarify this difference. A thing can be said to be in a certain state at a certain point of time. We say, for example, that this or that piano is currently out of tune or that it weighs 400 kilograms. The state – being out of tune or weighing 400 kilograms – does not contain any temporal determination. The temporal determination that this piano is currently in this state is an external determination, not an internal feature of the state. The information when the thing is in that state doesn’t make any difference to our understanding of the state itself. When we think about events, however, things are different. An event is something that happens to a thing or a situation; it designates a change or modification of the states in which the things are. When we talk about such a change in the states of affairs, the temporal determination becomes an essential, internal feature of what we are talking about: if the same states were to occur in a different temporal order or in a different rate of time, we would not be talking about the same event. An explosion, a turning point or an approximation are events, and not states, insofar as they are what they are only by virtue of their particular temporal development or shape.

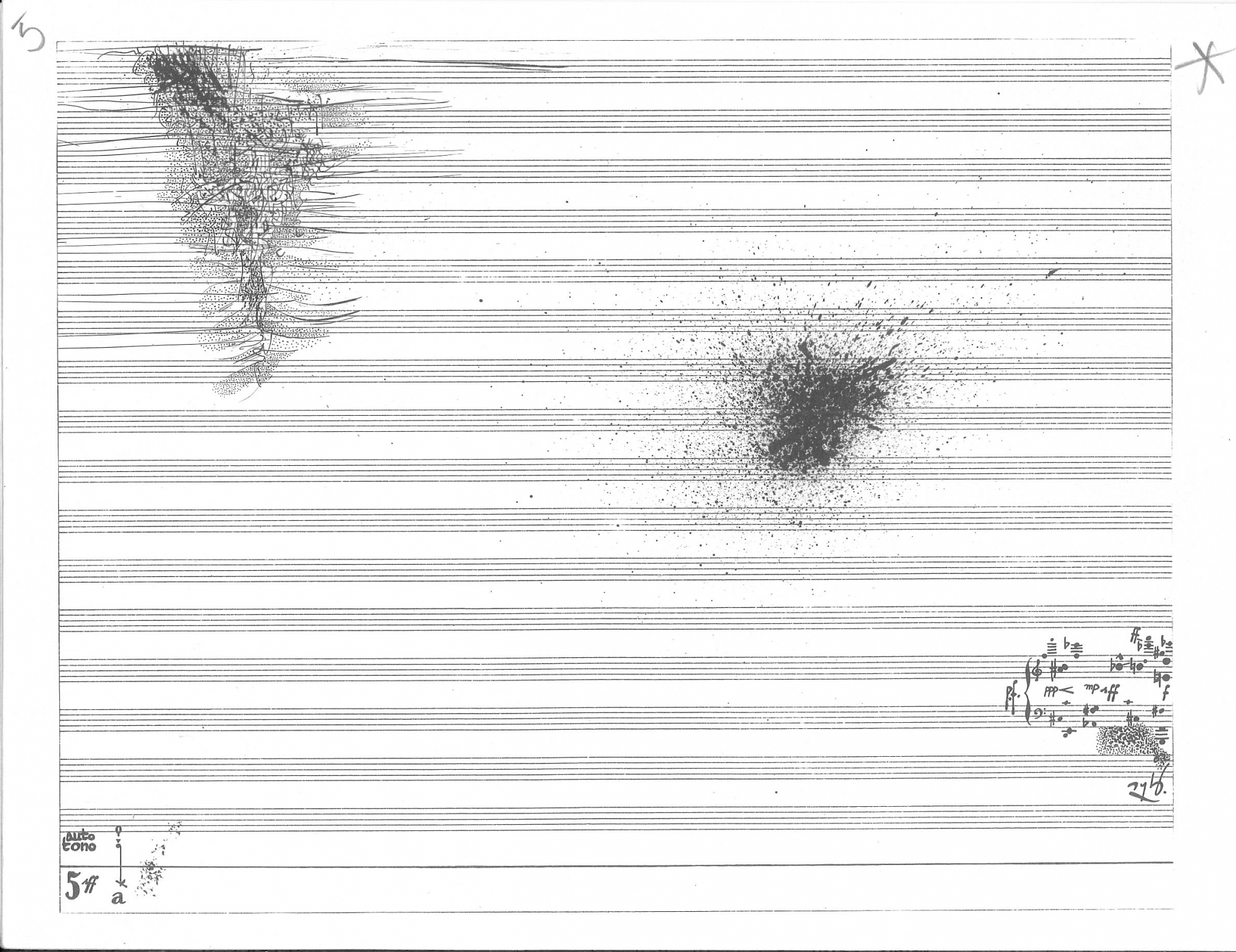

The distinction between states and events helps to clarify the paradoxical kernel of the idea of a sound installation. A sound is not a state, but an event: the temporal development and shape is not an external feature of a sound but an essential determination of what the sound is. A sound that develops differently in time is not the same sound. Sounds are not conceived as states in which things would be at certain points of time. They are no static properties of things. This is exactly what the artistic intention of sound installation puts into question: the sound installation is an attempt to work with sounds in such a way that they appear to be the features of a space. The artistic intention is to produce sonic shapes of time which are indifferent to their temporal development; shapes of time that suspend time. In Nuremberg, this idea was at the center of the very diverse sound works by 14 composers that were presented in the surreal waiting room Space Between conceived by Nile Koetting.

Among the works that elaborate this idea, three strategies prevail. The first is the literal repetition, the loop. Time is suspended insofar as one and the same temporal form appears identically all over again. It does not matter at which point in time one enters or leaves such an installation: one cannot miss a beginning or an end, because time is running in circles anyway. But problems immediately arise. If the loop is long, the temporal sequence within one turn of the loop will dominate the experience. Time is not suspended, but a temporal development is interrupted and starts again from the beginning. If, on the other hand, the loop is rather short, the repeated fragment of time will not suspend time either but will function as a measure of homogenous time. The looped bit of sound will be heard as a time unit like a beat or the ticking of a clock. The eternal repetition of the same then does not suspend but rather accentuates the ongoing and empty progression of time. In both cases, the suspension of time in space turns into an experience of temporal shapes of sounds.

A second strategy can be seen as an answer to this problem. Instead of repeating sound fragments, one single sound is stretched to the extreme. The paradigm would be the composition of drones. Here, sounds appear as states insofar as a single sonic event is never accomplished but is slowed down to the point of stasis. But this solution brings its own complications. In fact, the drone typically is not static at all, but appears as a continuous metamorphosis. Far from suspending time, such eventless processes are heard as a sonic image of the pure temporal flux. It is maybe the perception that comes closest to the objectless, undisturbed time consciousness: time without anything temporal.

A third solution is offered by the dissociation of time in what Stockhausen labelled the moment form. This is the strategy to elaborate a constellation of separated sonic events – independent moments – that appear in such a way that their order of appearance seems to be unimportant. Each sound complex is an independent moment among a multitude of moments appearing hazardously in continuous time. A moment form suspends time insofar as it does not matter when the moments appear. Not a sequence, nor a repetition, nor a stretch of temporal shapes, but a dissociation and particularization of unrelated time fragments. But again, time comes in through the back door. For it is obviously of the uttermost importance how these moments are arranged in time. Only in a certain constellation and in a certain order will a set of sonic events appear as dissociated moments whose temporal order is indifferent. The strategy consists not in abandoning the temporal organization of sounds, but in finding a very specific temporal order in which sounds appear not to be temporally ordered; a musical unorder of time.

The three strategies reveal themselves to be paradoxical: they long for the creation of an event that negates itself.

IV The paradox of a musical performance art

The ideal of a music installation would be an artworks in which musical forms of presentation intervene in an already spatially organized sound. They would introduce a performative element into the art of installation or transform the setting of the traditional concert by the means of installation art. The concert would be enfranchised from its traditional place in the bourgeois setting of the stage and enter the messy concretion of artistically determined environments. The model for this intervention is what we know as performance art. From its beginnings in the historical avantgardes, performance art has been understood as a disturbing intervention into social spaces. The idea of music installations would, in this sense, transform the traditional musical performance into a musical performance art.

The notion of performance art should not be confused with the loose idea of performative artforms such as theater, dance or music. In contrast to these established performative artforms, performance art is characterized by its anti-fictional impulse. A performance, in this narrow sense, disrupts the tissue of artistic semblances; it destabilizes the distinction between the fictional role and the real actor; and it blocks the well-established mechanisms by which the public and the performers disappear behind the staged world of illusions. In an artistic performance, the artist and the audience remain consciously present, here and now, with all their bodily, social, biographic and affective conditions and limitations.

This impetus of performance art can be transposed into the realm of musical performance. What it attacks then, is the establishment of musical fictions. A musical performance art would break with the seeming independent sonic world the bourgeois concert celebrates. It would tear apart the appearance of sound-relational coherence, of musical functions and narratives, of a tonal scenery behind which the real act of production is concealed. It would be a music of disillusion.

The paradoxical nature of this seemingly simple intention appears when one reflects on what there is to replace the artistic fiction. The answer seems straightforward: a performance performs not fictive acts but real actions in real social contexts. However, the theory of action and speech-acts has analysed the conditions that must be in place if a real action is to take place. The intention to really do something is not enough. Roughly put, one can say that, among those who are implied by the action, there must be a shared understanding of what kind of action is to be performed, what it means for such an action to succeed, whether the person is in a position to perform this action and whether the relevant context of such an action is actually given. For everyone concerned, it must be more or less clear what someone is trying to do, what it would normally mean to get it done and whether the present situation is one that allows for such an action to occur. Without a shared knowledge about the norms of action and the situation of its application, no real action takes place. To put it in a nutshell: real action is normalized, collectively intelligible behaviour in commonly known contexts. I can of course try to open a trial, declare war on a foreign country, buy a car or make a promise – but if those who are implied do not share my understanding of what it means to perform these actions and if they don’t accept that I am in the right position and situation to do what I’m trying to do, then no real action will occur. I will utter words and move my body without accomplishing anything.

These conditions are precisely not fulfilled by artistic performances. Or, even stronger: the strange beauty of artistic performances lies in the refusal to comply with these demands. For the very point of this kind of intervention is to disrupt normalized behaviour and to destabilize the common knowledge we take for granted in our everyday life. The Queer Magick Intervention by Wojtek Blecharz and Vala T. Foltyn that was performed as a strange sort of ritual in the ancient Reichsparteitagsgelände in Nuremberg manifested this unreal nature of artistic performances in many ways. The art performance displays elements of action and discourse not in a normal context, but in a situation where no one already knows what kind of situation and action is supposed to happen. The information about context and the norms of action which can be taken for granted in normal action is deliberately suspended or at least disturbed. This is also the reason why, for most of the time, actions that happen within an art performance do not have immediate consequences. When a performer humiliates the public, when she makes a promise, when she leads a ritual of initiation or makes a political declaration, all these actions are not actually performed, but merely displayed. For someone to actually humiliate, promise, initiate or declare, there must be a more or less clear and common understanding of who is addressing themselves to whom, in whose name and with what purpose. All this is far from evident within the suspension of normality at which an artistic performance aims.

The logical place of art performance is therefore a space in between. On the one hand, the performance breaks up and steps out of the traditional, theatrical construction of a coherent fiction. On the other hand, it does not enter the realm of real actions either. An illusionary character sticks to the words and gestures a performance displays as long as they do not subsume themselves under the norms and conditions of normal behaviour. Hence the broken bits of fiction that haunt the acts of a performance like a shadow.

The same can be said regarding musical performance art. For musical expression is, on a very basic level, necessarily bound up with fictionality. To express something musically always means somehow to fictionalize what is expressed. If someone just wanted to get something communicated to someone else, it would be ridiculous to express this content musically. To use the means of musical expression always means to refuse the most pragmatic and well-established way of transmitting information, to negate normalized communication and to say something precisely by not saying anything, to make something clear without drawing on shared understandings, to articulate a firm and obliging thought by the very act of suspending the form of propositional judgments. Hence, if music takes up the anti-fictional impetus of performance art and tears apart the veil of musical coherence, it cannot get rid of its fictional character either. The break with its fictions happens itself fictionally. The paradoxical intention of musical performance art can therefore be put as follows: it is the intention to create the fiction of a musical non-fiction.

The oxymoron of music installations seems to contain all three of these paradoxes that haunt contemporary music. To create situations, to compose sonic states and to tear apart the veil of musical fiction are paradoxical intentions that might be reunited under this new genre concept. It is possible that these intentions are just what they seem to be: incoherent artistic programs that will predictably produce well-known nonsense. However, in taking up these challenges, future artworks might also show that these intentions bear the potential to push the musical art beyond itself and generate something of which we don’t know what it is.