I hereby resign from New Music

by Michael Rebhahn

(transl. Wieland Hoban)

This text originally was a lecture held in Darmstadt at the Summer Course 2012, it was then published in the Darmstädter Beiträge 22 (2014). After this text came up in the roundtable discussion on „Critique in Darmstadt“, put together by Elaine Fitz Gibbon and Steven Takasugi at the Summer Course 2025, we republish it here to suggest it for reconsideration — with friendly permission by the author.

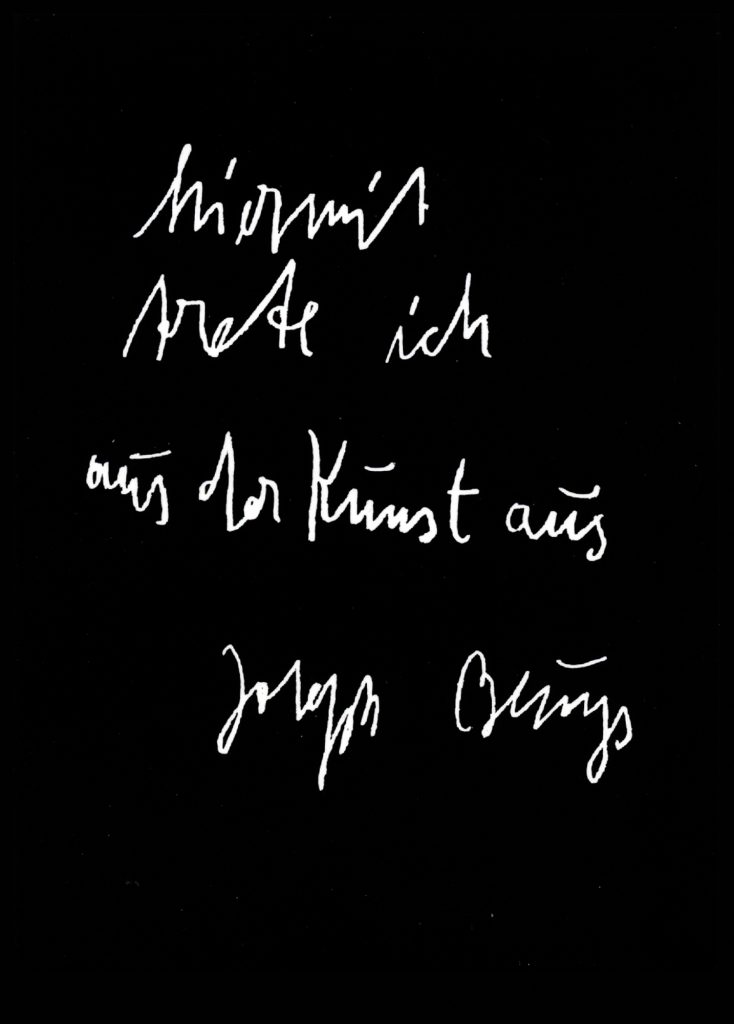

The rejection of collective descriptions has always been a matter of honour for artists. Applying a label to oneself voluntarily goes against the ideal of originality, lessens individual achievement and increases the danger of hasty interpretations and classifications. In almost all cases, it is the imaginatively conceived markings of apocryphal sub-genres that arouse the greatest displeasure among the labelled (the ominous »New Simplicity« of the late 1970s is a prominent example). For an artist to negate their allegiance to an art form entirely — and more still: to the sphere of art as such — is a less common phenomenon. One of the few such »deserters« was Joseph Beuys, who declared on a multiple postcard in 1985: »I hereby resign from art.« A stance that has recently begun to appear in the realm of art music, however, suggests that Beuys’s initiative might experience an unexpected revival.

»Essentially, what I do is not New Music«. — In conversations with a not inconsiderable number of composers of the younger and youngest generation, it does not usually take long for these words to be spoken. The emphasis on deviating from a label, from a conceptually and terminologically fixed genre, seems an inalienable part of their self-image. »New Music is what other people do«! A definition of precisely what they are distancing themselves from is not immediately clear, however. If anything, one tendency can be recognised: the aversion is directed at musical exhibits that content themselves with demonstrating a specialised knowledge of decorative material application without reflecting on the originality or, teleologically speaking, the necessity of what is formulated. It applies to compositions whose polished surfaces give an overly strong impression of arts and crafts, a music that has fallen prey to a self-referential sonic fetishism.

Taking up this argument, one can certainly say that a substantial number of contemporary compositions do not go beyond craftsmanship — beyond the demonstration of how they are made. The focus is on the effort to demonstrate a »state of the art«, conveyed in the varyingly skilled application of a material currently considered »progressive«. Often enough, one finds no more than a manifestation of this ability: as long as the product maintains an intactness of the external appearance, as long as it has an overlap of at least 75 % with the culture-historical topos of New Music, the composer has achieved their class goal. This form of box-ticking aesthetic is supported by an equally common and abstruse reception behaviour in which the essentially pejorative assessment »well made« is reinterpreted as a positive one: if one listens to the conversations in the intervals at New Music concerts, one encounters this somewhat peculiar form of quality judgement with notable regularity. Even listeners with a completely negative opinion of a composition still feel obliged to acknowledge certain details; they then tend to speak of »well-placed sounds« or a »subtly-judged instrumentation«. This mode of partial appreciation must be an exclusively music-related phenomenon. (At least, I have never attended a vernissage where someone said, »The pictures are ghastly, but the use of colour is brilliant«!) In music, by contrast, it seems that people are already impressed if the artist shows a grasp of certain tools of the trade. The quality of a work of art is thus confused in uncritical willingness with the quantity of technically competent details.

This mode of reception fixated on the way works are made ultimately has a fatal effect: a consensus ensues that composition is nothing more than the ability to »carry out« acquired techniques according to established standards of fabrication. As a result, New Music forfeits its claim to the status of art. It enters the realm of basic craftsmanship with an elevating prefix — rather like the »art of cooking«. And it is probably this tinkering in the haute cuisine of carefully prepared delicacies that makes some young composers resent being subsumed under the label of New Music. Instead of buying into the competitive logic of continuous material refinement or referring to the stringing-together of catalogues patterns as »composition«, the focus of artistic interest is shifting from the how of construction to the why of aesthetic substance — the question of a composition’s significance outside of an esoteric system of reference.

Pointedly put, the goal is to break out of the circle of the abetters of an escapist salon avant-garde that sees its duty fulfilled in the discreet rearrangement of sonic doilies, whether sewn in a complexist, algorithmic, spectralist or whatever other manner. In the younger generation of composers, the number of those who are content to have occasional success with »well-made« works and thus secure a com-fortable place in the committee of New Music trustees seems to be in noticeable decline. This distancing is expressed in the need to adopt a critical stance towards to the transmitted conventions, to exceed the familiar structure of commonplaces and question any consensus, instead of constantly varying those aspects of the materials that have already been identified. At the same time, it is the vital interest in the effects and perception of musical works outside of the scene’s shel-tered spaces, which have lost all connection with the cultural discourse.

Being a composer means being able to endure isolation. For an artist gambling on the relevance of their work for the aesthetic discourse, New Music is as inhospitable a terrain as one could imagine. Choosing the career of composer ultimately means choosing to work without having any effects to speak of. Reception outside of the time-honoured areas is virtually non-existent — not least because people there have become too fond of the image of arcane avant-garde circles, where being out of touch with the world is the foremost duty. On top of this, the cultivated ignoring of New Music has long since become accepted; the typical exponent of the species »people interested in art and culture« can safely feel up to date without having the slightest knowledge of current developments in music. Being a composer thus also means having to explain to everyone that one is not a »twelve-note musician« who produces »something like that Stockhausen«. Who or what the New Music composer is, however, cannot in fact be summed up so easily. In the following cursory »taxonomy«, I shall attempt to pinpoint at least a few facets of this little-known species.

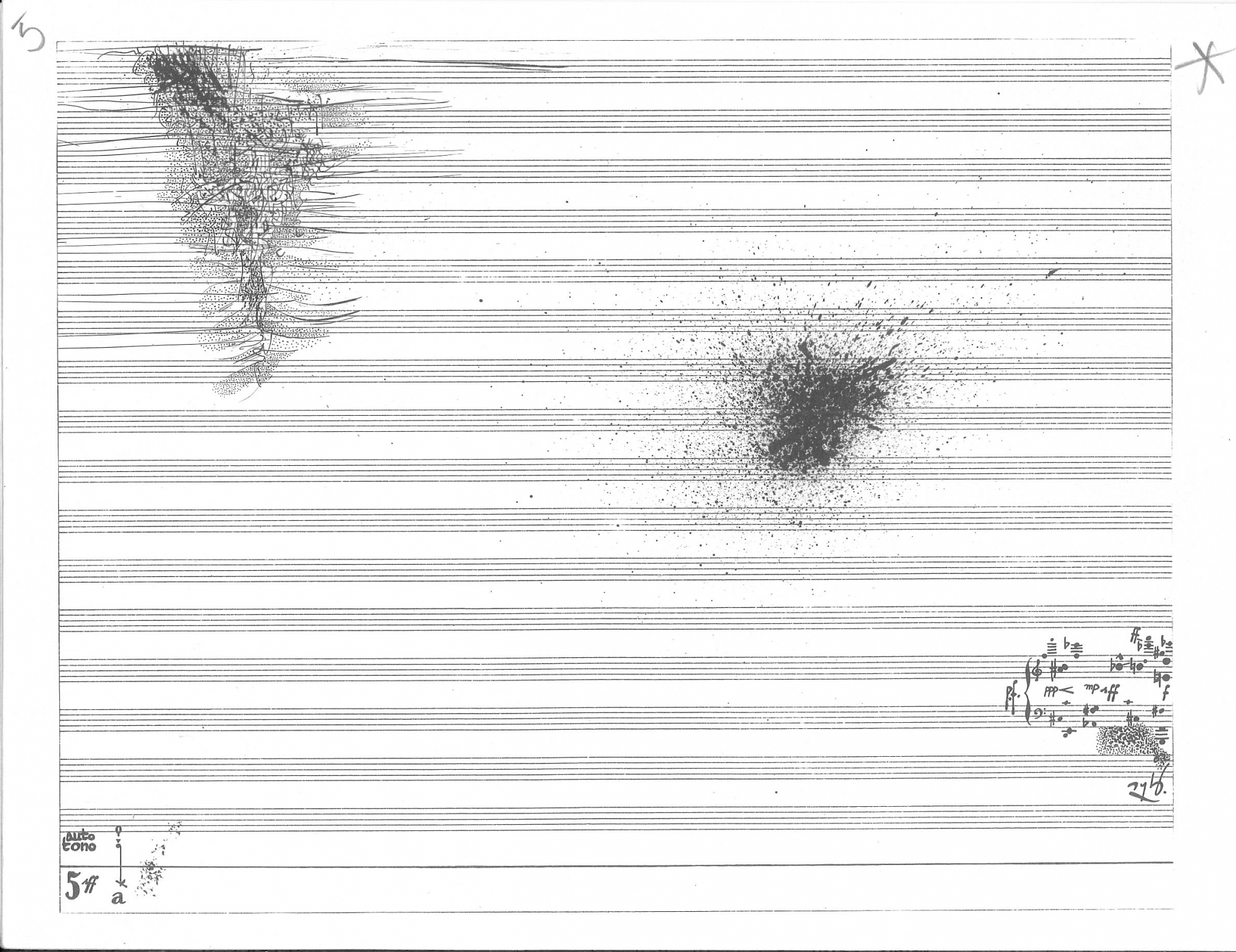

The conservator

The weighty name of this genre already expresses the equally diffuse and utopian task which the composer feels rests on their shoulders: their music must be new — and anew every time: nowhere is the Romantic ideal of the original genius as untouched as in the sphere of the musical. But permanent innovation is an especially precarious task, all the more so because the traditional resources still offered to the composer ultimately go against the edict of continuous renewal, as the development of most acoustic instruments was complete by the early twentieth century, if not before. In New Music, this stagnation has a lasting effect on the requirements generally associated with musical innovation. After the experimental structural games of the serial era, with all their ramifications and negations, had been absorbed into the body of a canonised repertoire of crafting means, the composer advanced to a strategist of outwitting: it became the royal road of compositional innovation to go against the grain of the historical apparatuses and establish a microcosm of sonic differentiation that ensured the survival of the artefacts of instrument-building on the one hand, and not infrequently exhausted compositional ambition in the routine montage of material variants on the other hand.

In time, however, the relationship came to be significantly reversed, and now the composers themselves seem to have been conserved by their reproductive media; the stubbornly perpetuated »progress of material« proves a dead end, and the technical limitations of instruments, along with the stylistic preferences of the ensembles, dictate the setting in which compositional work takes place. The commissioning system, which is controlled in substantial part by the ensembles, take care of the rest: composing for such instrumental combinations as bassoon, accordion and harp may correspond with the creative will of composers in individual cases, but more often than not, helplessness is successively compounded with compromises whose sum is subsequently premiered. In the youngest generation of composers, on the other hand, clear resistance to the role of the conservator and the conserved is becoming visible: the resigned acceptance of a historically dictated set of instruments is increasingly understood as a forced symbiosis that threatens to turn composers into cleaner fishes, useful parasites of an institutionally regulated food chain.

The brand

Surviving as a composer means making a name for oneself, establishing a brand. Names are metadata — they supply objects with supplementary information directed at authorities beyond the object: institutions and markets, a network of historically-grown conventions whose rules and constraints are so well-rehearsed that they are scarcely perceived as such anymore. Names thus reflect structures to which objects are allocated; contexts into which it is integrated and functions that it has to fulfil. Establishing themselves as a brand first of all brings the composer into an almost irresolvable dilemma: on the one hand, recognisability is a prerequisite for successfully launching one’s product as a »must-have« with a secure place on the programmes of festivals and repertoire lists of ensembles (at least temporarily); on the other hand, this can rapidly create the danger of being accused of lack of ideas: the label is compromised into a »trick«.

Membership in the circle of »indispensables« can certainly be extended through a clever creation of variants, and in some cases the recipients are placed in a state where lack of ideas is taken for personal style. Such tolerance is shown more to the traditional »firms« among composers, however, of whom there is no longer any expectation to constantly re-launch their product range. From those who cannot yet claim the status of established figures, however, permanent agility is expected: every work is, first and foremost, a recommendation for the next — the goal is to serve the determinants of the market. And before they know it, composers are trapped in a net of demands and conventions that largely marginalise the fact that their activity has any function beyond serving an industry based on intrinsic regularities.

The tinkerer

No artist works in an ahistorical vacuum; the path to independence necessarily passes through an engagement with tradition, and the aspect of internalising a canon of sanctioned materials plays a substantial part in this. During their training, composers usually spend their time appropriating different musical procedures and taking instruction in the existing conceptions and techniques. In this sense, an engagement with earlier models automatically influences any attempts to embark on a new one. The creative production of something new from the existing aesthetic material is due to an ultimately unquantifiable ars combinatoria. It breaks the available signs out of their accustomed surroundings and puts them together for as long as necessary until a new, unknown dimension becomes visible in them. The existing elements are taken off their course, reinterpreted, and brought into new constellations.

The epigonal modus operandi here is the securing imitation or variation of what is found, the restorative gathering of sufficiently tried and tested things; the originary, by contrast, is the striving to adopt a critical position towards established conventions, to the equally power-ful and alterable norms and agreements. »The creative artist executes things that exceed what is positively learnt«. [»Der schöpferische Künstler setzt Dinge ins Werk, die das positiv Gelernte übersteigen.« Peter Sloterdijk: Der Ästhetische Imperativ. Schriften zur Kunst, Hamburg 2007, p. 408.] That is how Peter Sloterdijk formulates it in his text The Aesthetic Imperative. One can find in this art of combination a variant of »wild thought«, that mythopoetical construction procedure described by Claude Lévi-Strauss as bricolage. It is not supported by rules or techniques that can be learnt and then simply applied; rather, in the ideal case, the composer is an »ignorant« who bravely steps onto the hazardous terrain of the experiment that is open to the future. The certainties that might subsequently develop are not preconstituted in the form of a learned system of task fulfilment, but come from a permanent interplay between attempt and reflection. Every placing, every choice of a position, a context or a correspondence changes the starting situation and demands new consequences. With the increase of conclusiveness, the sketch gains stability: while the material can still mean many things at the start of this process, there are many things it no longer means by the end.

The consumer

In so far as the composer does not want to limit themselves to the aforementioned role of the conservator, an engagement with the social reality of the musical outside of the New Music microstructure is inescapable. Ignoring the change in the conditions of music’s production, dissemination and perception would amount to an aesthetic oath of manifestation, and could only be in the interests of composers who enjoy being gravediggers of their genre. The position of the attentive, critical consumer who observes the mechanisms of medial conditions, judging their significance for the state of the material in New Music, is one of the central prerequisites for the conception of a maintainable way of composing.

For some years, efforts have been undertaken with impressive energy and monetary input to prove that New Music is not an elitist »art for experts«, and that it can delight even the »untrained« listener with unsuspected sonic experiences. Often enough, however, such admirable attempts only reveal the divide between idealistic spokespersons and potential recipients. One cannot blame an unsuspecting commuter who suddenly finds themselves being subjected to some form of proselytic address for asking, »What does this have to do with me«? Ultimately, this is the same question that an increasing number of composing »experts« are asking, and thus seeking to undermine the tacitly internalized reliance on hermetic credit systems. »What does this have to do with me«? The desideratum is to overcome the discrepancy between compositional work and aesthetic reality, and thus disavow a habit of production and reception where it is denied from the outset that even the composer is capable of proposing different models of world-experience.

For the composer, this means no longer being able to live in lovely Late Romantic coziness »alone in his song«. A music that claims social significance cannot dispense with detailed knowledge of that »outside«. In this sense, a further persona of the composer manifests itself in the role of the empiricist, who does not exclude insights from the outset as »inadequate« or »illegitimate«, and whose aesthetic bricolage is not influenced by categories of prohibition. Alternatively, of course, they still have the possibility of conceding at the next helpless enquiry that essentially, they do actually do »something like that Stockhausen«.

If the latent willingness of young composers to »resign« from New Music is more than a mere fashion, one of the most urgent questions for the genre in the immediate future will be how far the supposedly exotic activity of composition can justify its function in earthly life. What is needed is a music that asserts a perceptible and effective position in the line of artistic disciplines; without abandoning its distance from the interchangeable daily media noise, without affirming that equally utopian and unattractive formula of generalisation (»art = life«) and without pandering to the advocates of a smoothed-out wellness avant-garde through regressive trivialisation. The distance of young composers from their own profession holds the real opportunity to free contemporary music from its isolation. The willingness to react to the changes in music’s conditions of production, dissemination and perception, and no longer to tolerate the respective indifferences of the genre, promises outlines of a compositional approach connected to the present: a timely New Music.

Published in German as »Hiermit trete ich aus der Neuen Musik aus.« In Darmstädter Beiträge zur Neuen Musik, vol. 22, edited by Michael Rebhahn and Thomas Schäfer, Mainz 2014, p. 89–95.

Michael Rebhahn is editor for contemporary music at Südwestrundfunk (Southwest German Public Broadcasting). He studied musicology, art history, and philosophy (PhD dissertation on the musical aesthetics of John Cage). From 1997 to 2000, he worked on the editorial staff of the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik and as an author for the TV magazines Kulturzeit (3sat) and Kulturweltspiegel (WDR/Das Erste). Since 2000, he has produced numerous radio features on contemporary music. As an author, he publishes in German and international music magazines as well as for institutions such as the Biennale di Venezia, the Goethe-Institut, and the Ernst von Siemens Music Foundation. Teaching assignments and guest lectures have taken him to the University of Music and Performing Arts Graz, the Folkwang University of the Arts Essen, the University of Fine Arts Hamburg, and Harvard University, among others. He has been jury member for the World New Music Days, the Villa Aurora Fellowship Los Angeles, and the artist-in-residence program of the Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics. Since 2012, he has curated the lecture and discourse programs at the Darmstadt Summer Courses and is co-editor of the series Darmstädter Beiträge zur Neuen Musik. Since 2021, he has been a member of the board of trustees of the SWR Experimentalstudio Freiburg.

Copyright holders who could not be reached are requested to contact us for legal settlement.