Allusions to Music, Sexuality and Skin Color. In Conversation with Georg Friedrich Haas

by Jim Igor Kallenberg

This text was originally published in Musik-Konzepte 199: Georg Friedrich Haas (2023), edited by Ulrich Tadday and translated by the author with the friendly permission of the publisher edition text+kritik.

JIK: Sex is not music, and music is not sex. Music and sexuality are not identical. They relate to each other. I would like to ask you about their relationship.

GFH: Why are you asking this question of me? Because I have come out as a member of a sexual minority? I have no idea if and how my sexuality is connected to my music. I only know one thing: I feel a deep, spiritual, asexual love when I compose – which I feel in a very similar way when I caress my wife’s face.

JIK: Since, regarding your music and person, the relationship between sexuality and harmony is so often discussed in a vulgar way, I would like to discuss critically rather than polemically – even if I don’t want to spoil anyone’s fun. This applies to both parts: both sexuality and harmony are often treated polemically and one-sidedly, as if microtonality, for example, simply extends the tonal range by a good many tones. In this way, tone ratios could be subdivided infinitely, and we would have ‘infinite progress’ – but not at all infinite pleasure because that is not what music is about. The superficial exploitation of these questions comes at the expense of a critical discussion of the connection between sex and music. Sexuality is a driving force of our actions, thoughts and lives and, therefore, also of our composing. Music, on the other hand, not only has personal significance, but a work initially stands for itself. Sexuality and music are each independent expressions of human activity and forms of human life with their own dynamics. They articulate their respective emancipation in their own forms and cannot be completely translated into one another. And yet, they are interrelated. The questions we could address would be how nineteenth-century sexuality relates to today’s sexuality and how nineteenth-century harmony relates to contemporary harmony. And then, we could ask about the connection or relationship between the two.

GFH: Of course, you are free to discuss the relationship between harmonics and sexuality as productively as you like. But I would ask the question: What are we talking about? Are we talking about sexuality itself – or about the image we have of it? Of the harmonics themselves (oscillations, mergings, frictions etc.) – or of the image we form of them (i.e., the notation and verbal nomenclature of the harmonies)?

JIK: Aren’t both music and sexuality precisely connected here, concerning, for example, form, melody and harmony? Certain relations provoke tensions, climaxes, as you say: oscillations, mergings, frictions. A different harmony would have to take on a different form. And in the same way, the sexuality that was reflected in and shaped this other musical structure would be a different sexuality. Allow me to articulate it simplistically: it could be a kind of music that was not dependent on climaxes – although sexuality without tension and at least projected climaxes may contradict the very concept of sexuality. But just as the overcoming of tonality is a utopia, so may be the overcoming of sexuality.

GFH: Susan McClary pointed out the strong connection between sexual and musical climaxes in nineteenth-century art music decades ago. I remember a lecture she gave in Darmstadt where she spoke at length about the differences between male and female orgasms and transferred that to music. Orchestral musicians also know this and make their crude jokes about it.

I firmly reject your formulation: ‘But just as the overcoming of tonality is a utopia, so may be the overcoming of sexuality’. The equation it contains between overcoming tonality and overcoming sexuality is wrong. Sexuality is an innate natural phenomenon. Tonality is not.

The ‘overcoming of sexuality’ is not a utopia but a dehumanization. Tonality has not been ‘overcome’, it has been lost.

The loss of tonality is painful.

Schoenberg could still believe that tonality was dispensable while retaining everything else. But unfortunately – and it is really painful – this is not the case. Everything is lost: the classifications of chords, the relation between harmony and melody, the metrical system, the traditional principles of form …

Instead, an infinite wealth of new possibilities in sound and time has been gained. I am stunned by this wealth and know that my life is too short to navigate this new confusing beauty. In my opinion, there is a parallel to the ars nova of the fourteenth century: at that time, music was subtly sensing the resonations of a new space that was only later explored by Ockeghem and Dufay.

Today, I am only able to take the first steps in this new world. The next generations of composers will move on. What I try to do as a composition professor is to teach people to think in music. Not about music.

JIK: When you mentioned Schoenberg, I thought of the octave question: the identity of the octave is the cornerstone of traditional harmony. Wouldn’t the microtonal approach also have to break with this, insofar as the octave has its own value?

GFH: Not should, but must. That is one of the basic tenets of my lecture at Columbia University in New York, ‘Music beyond the 12-tone system’. Allow me to give you a few examples.

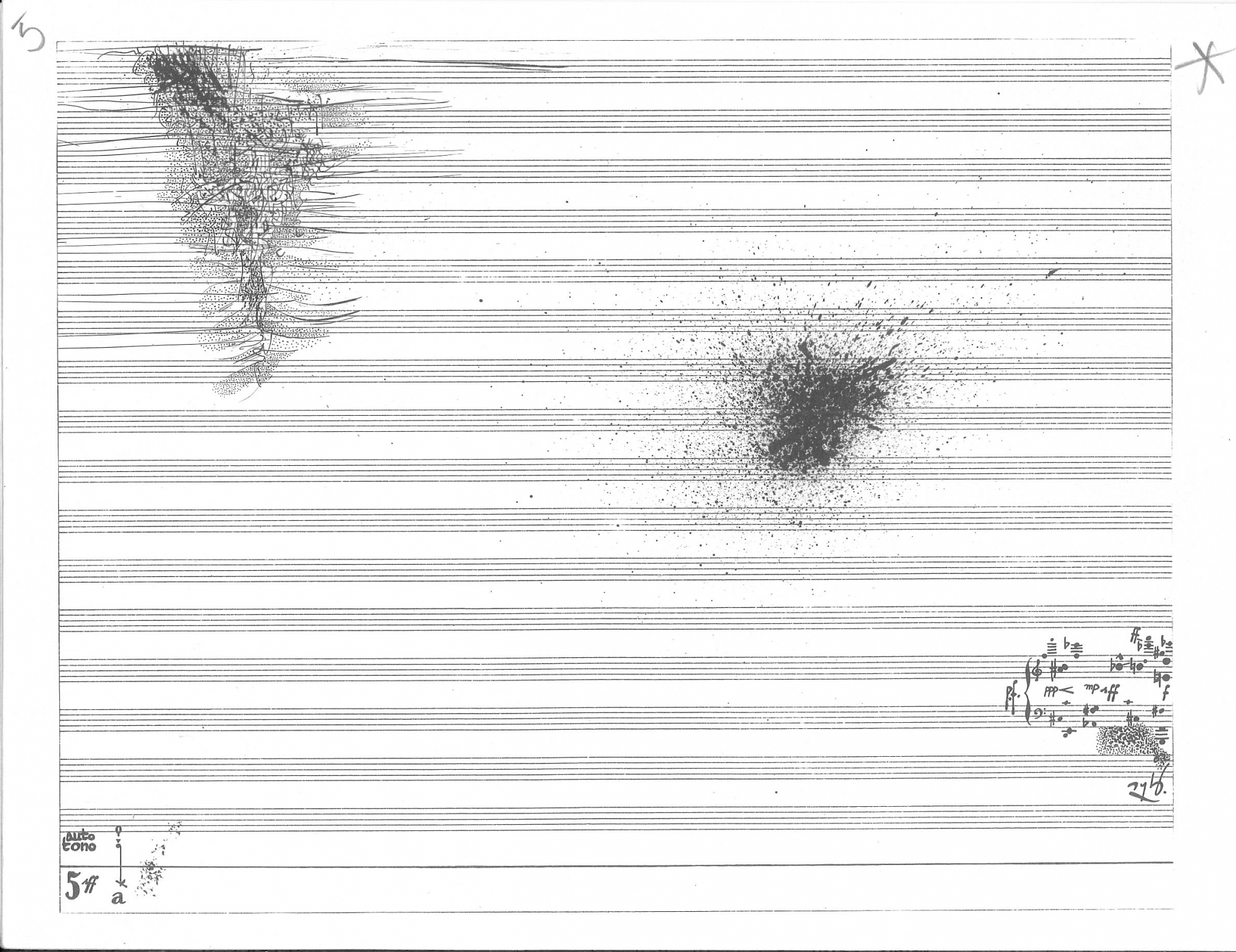

A C-major chord remains a C-major chord even in its first inversion; a little different (a sixth chord), but basically the same (fig. 1a).

The triad d’-a’-quarter-tone lowered c” sounds almost like a quarter-tone approximation to the overtone series (4:6:7). If we raise the d’ an octave higher, it becomes an abstract sound consisting of two intervals of equal range (whole tone + quarter tone each), a mathematically exact half of a pure fourth. There is no recognizable tonal relationship between these two chords (fig. 1b).

An overtone chord up to the eleventh partial sounds homogeneous; in this register, the progressively narrowing [kleiner werdenden] major seconds merge. If we transpose the eleventh partial an octave down, we hear an unpleasantly dense cluster of tones between e’ and g’; the original almost consonant chord becomes very oblique (fig. 1c).

The same interval changes its meaning in different octaves. The difference between the tempered minor seventh and the overtone seventh 4:7 is very large in the middle register. Two octaves lower, the difference between these two intervals is barely perceptible (fig. 1d).

In my ‘office’ at Columbia University, there are three differently tuned pianos. Here, I can demonstrate these examples (and many more) acoustically.

In the past, the octave position was hardly part of music theory, but in the great works, you can sense the careful attention with which these positions were set. In Beethoven’s piano sonatas, for example, the registers are structural. In Mendelssohn’s Klangfarben compositions, the octave positions (and their instrumentation) are musically constitutive. There is a fragment of a horn concerto by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, which was completed by his disciple Franz Xaver Süssmayr. In Mozart’s instrumentation, the D major chord has the position of the overtone chord, and in Süssmayr’s instrumentation, only D, F sharp and A are in different octave positions – here, the difference between a master and a non-master can be measured.

JIK: I consider this to be an essential aspect of the emancipation of dissonance insofar as it emphasizes the primacy of the particular over the whole. The subordination of the individual tone to a function in the basic key corresponds to the subordination of the part drives [Partialtriebe] as a function under the genital primate in sexuality. This may be where sexual and tonal emancipation meet. If we consider the music of modern societies as an expression of a specific modern freedom, then it may be here that artistic taboos and sexual taboos are analogous. Or, if you will, sexuality and music encounter common obstacles and accordingly, the emancipation of the dissonance and sexual emancipation act in association without being identical.

GFH: ‘Emancipation of the dissonance’ – what a terribly Eurocentric term. Listen to gamelan music. Or gagaku. There are no ‘dissonances’ that have to ‘emancipate’ themselves. On the contrary, the oscillations (‘dissonance’ in traditional European thinking) create a sense of spirituality. This is, by the way, also the case in European music. It is the so-called ‘dissonances’ that give us intense musical sensations. In J. S. Bach’s St Matthew Passion ‘… voll Schmerz und voller Hohn!’ it is the dissonant e’ in the tenor that makes us shudder with sheer horror (fig. 2). The same chord can be found in Schubert’s Winterreise: ‘Fremd bin ich…’ – followed by an even sharper dissonance in the prelude (fig. 3).

Even microtonal ‘dissonances’ can be found in traditional European music – but they are not notated. For physical reasons, mechanical organs cannot produce pure intonation – no one can control the inevitable spontaneous intonation fluctuations of the pipes. The reverberation of the church interior covers the sound with a velvety cloak, creating pleasant microtonal clusters that (as with gamelan and gagaku) evoke feelings of spirituality. Opera singers often intonate a little too high to be heard more clearly – the microtonal intervals that are created with the orchestra touch the audience deeply. Or they use wide pitch vibratos that achieve microtonal tensions with beautiful regularity.

‘Emancipation of sexuality’ – I can’t compete with the bisexual orgy that Mozart and da Ponte put on stage at the end of Act 1 of Don Giovanni. Especially as there is a social undertone (the imbroglio of three dances representing different social classes), which is even more radical than the erotic allusions. Sexuality on stage – that’s really not new. It has always been there. I consider the seventeenth scene of my opera Nacht to be the most beautiful depiction of sexuality in my operas: old Hölderlin appears on stage in three different scenes. First, he writes poetry in the fourth scene. Then, he eats and drinks silently in the tenth scene. Finally, in the seventeenth scene, he masturbates. There is nothing provocative. Just existence as it really was.

JIK: Let me put it the other way around. If certain people are tempted to exploit your personal sexuality conversationally, perhaps they have a good reason to do so. This intuition might be on the right path, leading beyond gossip concerning the music itself. One could certainly argue that your music does not necessarily lean toward the harmonic dynamics of the sonata form, nor does it function like the dissolution of tonality in the Schoenberg school, nor does it function like serialism. The utopia of a liberated sexuality could be articulated as a form-dynamic component of the music itself. So, if we’re already talking about it, then let’s talk about it properly.

GFH: Utopia of liberation – yes. But not only in sexuality. I had to liberate myself from many things in my life.

I grew up in a Nazi family. I liberated myself from that.

I liberated myself from the German nationalist Protestantism of my parents’ home and converted to Catholicism.

Then, I liberated myself from Christianity in general.

I liberated myself from the shame of my sexual orientation.

I liberated myself from the constraint of having to organize my compositions according to notational laws.

I was vegan for a while.

I had a small garden set in woods and meadows. At some point, I realized that I had to kill 20 voles, 200 slugs and 2000 aphids, just to harvest a few broad beans. It’s better, I thought, to kill a single pig and feed 20 people. I then also liberated myself from veganism.

JIK: Forgive me for insisting: I am concerned with an objective dimension of sexuality, that is, the extent to which it is reflected in music as a spiritual and physical sediment of human activity. Plato already thought that without the pleasurable, quasi-erotic appeal of things, we cannot entertain any intellectual relationship with anything at all. The understanding of music as a moment in this dynamic is obscured by the taboo which is expressed in sniggering and the moral judgment of individual preferences and practices. Of course, music is also – if not only! – one of the forms for cultivating sexuality, in the form of love and violence – and of many other things: of dominance, powerlessness, curiosity, submission and, not least, of freedom as well as of barbarism. This can be articulated in the material, in the way it is treated, in forms of progression, formal dynamics of the unfolding of a musical work, harmonic constellations, internal tensions and structures. Without, as I said, being reducible to them.

GFH: You said that very well. I do not need to add anything to it.

However, I would like to emphasize that, for me, addressing racism is central here. This directly affects me personally in two ways: on the one hand, there is my wife, who belongs to the African diaspora, and on the other, my younger daughter, who is between Europe and Japan.

JIK: I can hardly conceive of it as a musical theme.

GFH: Then you probably also find it difficult to conceive of the revolution in Poland in 1830 as a musical theme. Or Wellington’s victory. Or the Passion of Jesus Christ.

Are you familiar with my works I Can’t Breathe (2014), Hyena (2016) and Sycorax (2022)?

JIK: In a very mediated way, sure. I know the works you mention. However, I find it difficult to introduce differences in skin colour where they don’t actually exist, namely in the world of tones.

GFH: Well, you are wrong. Difference in skin colour also exists there. For the three strings of c’ in a piano, it doesn’t matter what skin colour the finger that presses the key has. But the colour of the skin does play a role in whether or not the person who wants to press this key has had access to this instrument. Whether he or she was able to learn it or not. Whether he or she had access to the concert hall or not. The colour of someone’s skin also determines whether they are perceived as a composer or not.

If we compare the two composers, Julius Eastman and Harry Partch, they have things in common. One difference is that Partch was discovered and promoted by Guggenheim. That was a good thing. But Julius Eastman was neither discovered nor promoted. When I listen to his great music, I am overcome with anger: what could this brilliant man have given us if he had been given the same opportunities as John Adams, or like me – or at least like Harry Partch! Eastman was African American. That’s why he was ‘invisible’.

I didn’t choose for the issue of racism to come into my life. My third wife was from Japan. And suddenly, I was confronted with day-to-day racism. Now, I am lucky enough to be with the love of my life: Mollena Lee Williams-Haas. Her ancestors were deported from Africa, and for centuries, they were not considered human beings in the eyes of the law but objects. My wife doesn’t know where they came from. A DNA analysis pointed to Kenya and West Africa. About 18 per cent of her ancestors were white: slave owners who had raped their property. When she was five years old, she realized for the first time what racism meant. She had been playing with a girl of the same age who was suddenly called out by her mother. Then the little girl came to her once again and said sadly: ‘I must not play with you because you are a nigger.’ When she sits next to a white man on the subway in New York, they both know: his great-great-great-grandfathers had the right to whip their great-great-great-grandfathers and rape their great-great-great-grandmothers. I’ve witnessed my wife sitting at the wheel of our just-parked car, trembling with fear, not daring to get out – we had pulled off the highway to get a coffee at Starbucks, with a police car behind us. No, it wasn’t dangerous this time, the cops just wanted to have a coffee, too.

And as a child back in Austria, I myself played a game, the name of which translates to ‘Who’s Afraid of the Black Man’ and sang a German song called ‘Ten Little Negroes’, we ate so-called Negro Kisses (chocolate marshmallows) and grew up in a Nazi family that tried to instill in me the lie that dark-skinned people were ‘inferior’. All of this resonates when I write my music. The pain of it. But also the certainty that healing is possible.

JIK: I can well imagine that the way in which ‘race’ is imaginatively dynamized creates obstacles for white people to identify with a black lead role; in other words, that unconscious racism is a big problem in art. But in the field of contemporary music, you’ll hardly find anyone who would explicitly describe themselves as racists. But, to stay with opera, there are also people, for example Jessye Norman, where it was obviously possible to identify with her without the colour of her skin preventing the recognition of her art.

GFH: Yes, Leontyne Price and Jessye Norman made their way in a world that was not built for them. That is admirable and proves their great artistic abilities. When they were on stage, many people identified with them. What everyday life was like for them is written on another page.

You mention ‘unconscious racism’. I have to be very careful now not to get emotional – as I said, I have been confronted with racism in my daily life since 2005. It is almost always supposedly unconscious. And it also comes from people from whom I would never have expected it. I have learnt to be strict. When someone I had worked with for decades told me in a conversation that people of different ‘races’ emitted smells that were perceived as unpleasant by each other, I broke off contact. I told him sarcastically that I couldn’t put him through the scent of my wife. It wasn’t just once that we discussed blackfacing with friends. Mollena explained that it hurt her deeply – and the people we spoke to showed no empathy with her, didn’t ask her questions, didn’t want to know about these injuries, but simply told her in her face, cold as ice, that the ‘freedom of art’ was more important than her pain. Anyone who does that must expect to be labelled a racist.

At this point, I have a request to all people reading this text. Don’t ask, ‘Who were the pigs that behaved like that?’ Because there are millions of these pigs in Central Europe. Please ask yourself whether you cannot find traces of these piglets in your own thinking. Because this – and only this – is how racism disappears.