Critique in Darmstadt. Roundtable discussion

with Steven Kazuo Takasugi, Elaine Fitz Gibbon, Martin Iddon, Patrick Becker and Jim Igor Kallenberg

The following is a transcript of the the roundtable discussion in response to the brochure “Specters of Kranichstein: What was the Darmstadt School“ by Jim Igor Kallenberg. It was held on July 22, 2025, 2pm during the Darmstadt Summer Course at Lichtenbergschule, in Takasugi’s teaching room 313, and transcribed by Lucian Spohr and Christian Gregori; for the opening statements we used the speakers‘ written notes if provided; speakers who have not authorized the use of their names have been anonymized.

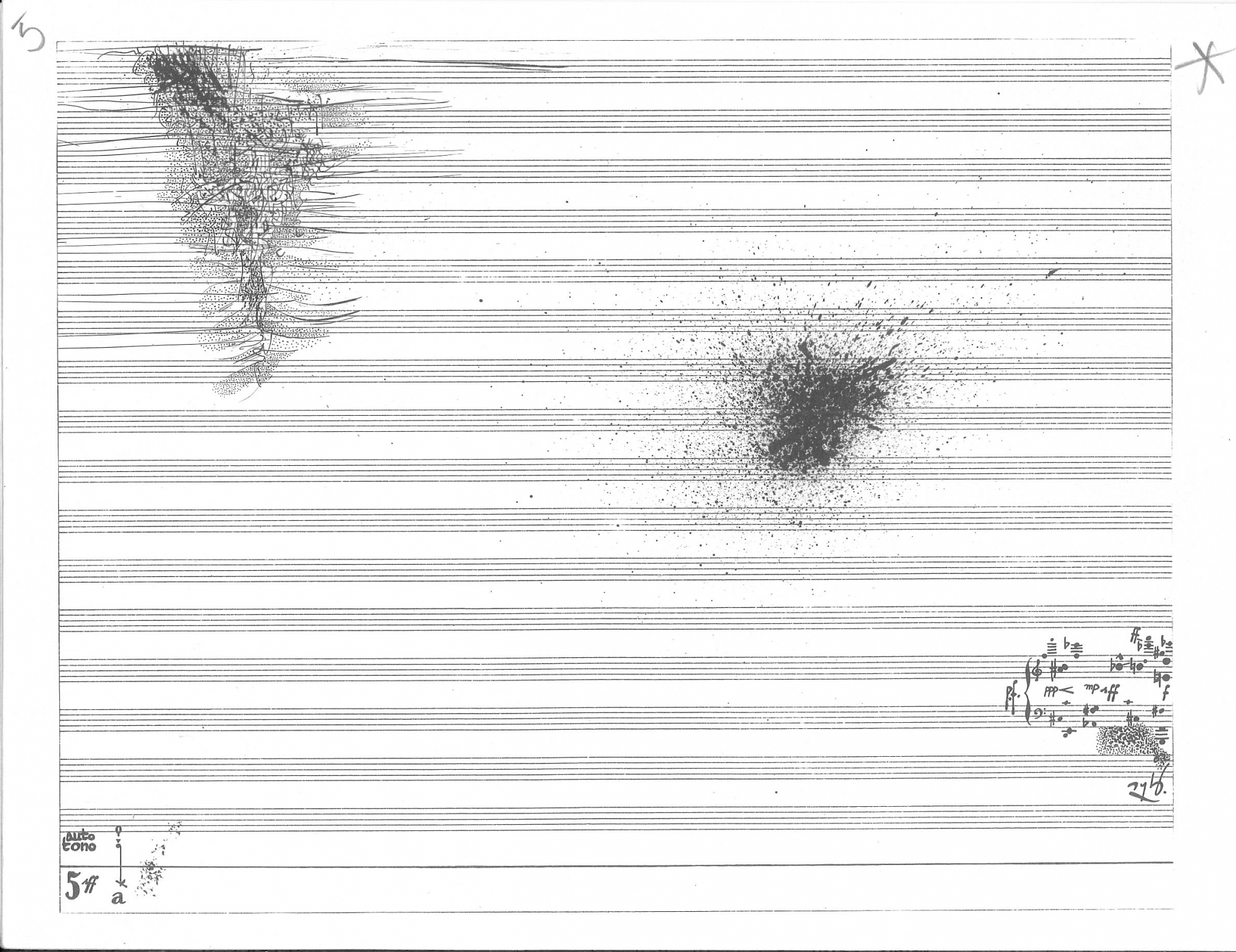

(photo: IMD and Kristof Lemp)

Introduction

Thank you all very much for being here today at this mini-workshop, “Critique in Darmstadt.” My name is Elaine Fitz Gibbon; I am a historical musicologist who works on avant-garde music, in particular experimental music theater and instrumental theater, from the mid-twentieth century until today. Currently I hold the position of Valentine Visiting Assistant Professor of Music at Amherst College in Western Massachusetts. I’m thrilled to be here as the moderator and respondent for this panel, and would like to thank Steven Takasugi for organizing and providing the space for this workshop!

So the format for today, as Steve mentioned earlier this morning, will be in two parts, each lasting 90 minutes. For the first part, the roundtable, each of our four participants, whom I’ll introduce shortly, will present an approximately 10-minute position paper. Following the four papers, I will provide a brief response and some questions for the panel to discuss, for about 15 minutes. Thereafter, we will open the conversation up to all of you and invite you to ask questions and contribute to the discussion, for which we will have approximately 25 minutes. That will bring us to 3:30pm, at which point we’ll have a slight change of format, and I will present a compilation of a 90-minute selection of films by Mauricio Kagel, Alfred Feussner, and others, which relate to some of the themes we’ll be discussing this afternoon, posing questions about sound, music, history, and the listening body.

So I’ll go ahead and introduce our panelists!

First, we will hear from: Jim Kallenberg, author of the brochure “Specters of Kranichstein: What was the Darmstadt school?” which you can purchase a copy of, as of this morning, in the Book Store thanks to Wolke Verlag! Kallenberg is a research assistant at the musicology department of the Goethe Universität in Frankfurt, where he is completing a doctoral thesis on Richard Wagner and avant-garde music; he has also been a visiting scholar at Columbia University with Lydia Goehr. Kallenberg is on the board of the Frankfurter Gesellschaft für Neue Musik; he is the co-founder of the platform for criticism partisan-notes.com, which has hosted a Visite Critique at several festivals since 2022—for which you should look out next week! –; and he works as critic and dramaturge in both institutional and underground music scenes (of old and new varieties).

Following Jim’s contribution, we’ll hear from: Martin Iddon, who is a composer and musicologist. His books, New Music at Darmstadt, John Cage and David Tudor, John Cage and Peter Yates, and The Cambridge Companion to Serialism all appear with Cambridge University Press, while his book John Cage’s Concert for Piano and Orchestra (co-authored with Philip Thomas) appears with Oxford University Press. His music has been released on four portrait CDs, pneuma, Sapindales, and Naiads (all on Another Timbre) and Hesperides (on NMC). In 2021, his solo tuba piece, Lampades, won the Ivor Novello Award for solo composition.

Following Martin’s contribution, we’ll hear from Patrick Becker, who is the director of the Wolke Verlag publishing house. He received his PhD from Berlin’s UdK (University of the Arts) in 2021. Prior to this, Becker studied musicology, German literature, and philosophy at the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. Following his PhD, Becker held a postdoc position at Leipzig University from 2021 to 2023. He is the recipient of many prizes, including the Humboldt Prize for his masters thesis in 2019, the Forum for Young Authors of MusikTexte, likewise in 2019, and most recently, with the Reinhard Schultz Preis für zeitgenössische Musikpublizistik 2024, for which he will be honored tomorrow evening! Beginning in 2019 Becker began work as an editorial advisory board member at Positionen: Texte zur aktuellen Musik, and since 2024 has also served as co-editor of that publication.

And last but not least, I’d like to introduce Steven Kazuo Takasugi, who is a composer of electro-acoustic concert music. He received his doctorate in music composition at the University of California, San Diego. He is currently an Associate of the Harvard University Music Department and lives and works in the Boston area. He has created masterclasses in New York City, Singapore, Stuttgart, Tel Aviv, Darmstadt, Bludenz, Dublin, Melbourne, and Cambridge, Massachusetts and has taught at the University of California, San Diego, Harvard University, California Institute for the Arts, and the Kunitachi College of Music in Tokyo. Takasugi is also an essayist on music and was one of the founding editors of Search Journal for New Music and Culture. He has organized numerous discussion panels and fora on New Music including colloquia and conferences at Harvard’s Music Department and the Darmstadt Forum.

Please join me in welcoming our panelists!

Jim Igor Kallenberg:

Thanks for inviting me to this, Steven and Elaine. It is only thanks to you that I’ve been invited here and am speaking here, because I cannot reject an invitation from Steven Takasugi, the music and personality of whom I admire so much and so profoundly to not want to live up to anything that he thinks makes sense. I’m grateful that my little brochure gave impulse to initiate this exchange, but for me, writing it felt not like an initiation, not like a beginning, but like an ending – an ending to 10 years of trying to organize criticism in Darmstadt, which made me the party spoiler and really the persona non grata of Darmstadt and was met with all measures of authority by that institution that fears nothing more than people exchanging ideas that are not curated. I think they have good reasons why this conversation does not appear in the online announcements of the Open Space. Neither does the Visite Critique [the Visite Critique sessions were announced in the Open Space schedule after this event]. All of that is very unpleasant, frustrating and hurtful. That is why it felt like an ending to my activism in Darmstadt, like my gravestone in Darmstadt.

But Steven reminded me of something that I have to admit: A gravestone is at the same time the place from where the ghosts, the specters arise. So, if the industry will succeed in banning the specters of criticism or if their haunting voices will be heard, is up for the future. Criticism is to be organized for the death of criticism in Darmstadt to be turned into its new life, its afterlife – or otherwise, with me will have been executed the last critic in Darmstadt.

In partisan notes which was an attempt to organize criticism in new music we opened our statement of purpose with a claim: There is no art without criticism. What does this mean? Adorno illuminates it saying that to produce an artwork is to produce an object of which we don’t know what it is. If there’s no prefabricated function in the art object, the question what it means and that is, how it is to be experienced, is not self-evident. This lack of self-evidence, that is, that impossibility to identify the object with a predetermined purpose, function and experience, makes it possible and necessary to make sense of it through critical interrogation, to explore the forms of experience it produces, to even transform the conditions of subjective experience at all. Susan Buck-Morss, co-editor of Adorno’s collected writings, put it this way: The task of the artists „is to sustain the critical moment of aesthetic experience. Our task as critics is to recognize it.“

So, without critique, the possibility of aesthetic experience just passes unheard. Under the condition of the culture industry this experience is repressed in an organized way. The form of organization of experience of new music ties it to the very rigid functions of marketing, funding, promotion, and seeking one of the very few jobs, commissions, gigs. This also and especially accounts to the state protected pity craft of new music. The horizon of experience narrows. Artists either, as Buck-Morss said, and Steven Takasugi suggested on his lecture this morning, „opt to go underground,“ or spend most of their time, creativity and productive capacities in writing applications, cheering their colleagues, begging for state or private funding in claiming what functions their project fulfils for society and the state. Festivals do the same, promoting new music as a whole. New music thus is the object of promotion, not of critique. Its function and thus the ways to experience it aren’t interrogated but determined. We produce only objects of which we know what they are. On the level of experience that is boring and embarrassing.

There’s a psychologic-ideological mechanism that then projects the embarrassing unfreedom of experience in the present to the past: if we can’t be free, freedom is just not possible, so we have to reject the idea that freedom was considered an opportunity in the past. My essay tried to dissociate that identification of the past with the present.

So, what do people say about the past of Darmstadt, given the name of the Darmstadt school? I reduce harshly: Either people want to promote their own work to the industry by legitimizing it as continuation to the Darmstadt school by which they mean serialism as a style of composition. Or people feel intimidated by the authority of this style and claim there never was such a thing as the Darmstadt school, but Darmstadt was always pluralistic, and so it should be, and so am I. The common ground both sides share, though, is that they take as criteria for the existence of a Darmstadt school a positive composition method or style, serialism, the existence and authority of which they either affirm or reject.

What I show in my brochure is that this has nothing to do with what the protagonists of the Darmstadt school thought of when they proclaimed it. Karlheinz Stockhausen, Luigi Nono, Pierre Boulez, Darmstadt founder and first director Wolfgang Steinecke and critic Theodor Adorno – when they talked about their Darmstadt school, they didn’t think of its content to be any positive style of composition, but in the opposite, the critique of any positive style of composition. The school they proclaimed was to negatively relate different ideas of music composition to each other in theory and practice to make sense of their own activity through critical self-reflection. They thought of Darmstadt as the organized self-criticism of music history.

This idea is repressed today. And this is how this question of the past – what was the Darmstadt school? – can turn to the present. We can imagine the past only with the categories of the present, so if today new music is only about marketing, power structures and jobs, we think the past must have also been about that, and these guys were just pushing their careers. That’s how the present represses the possibilities of the past and thus blocks potentials in the present.

Darmstadt was an attempt to organize criticism against the organization of music in the culture industry. In the course of its history up to the present, Darmstadt itself became the institutionalized liquidation of critique. This can only be met by organized criticism, by building up contexts in which critical exchange is cultivated between producers, critics and audiences about their aesthetic experience, independent of the administration of musical experience by the institutions of culture industry. Only thus can the empty commodities of culture production be transformed into art and sustain the critical moment of aesthetic experience.

Martin Iddon:

It’s first worth rehearsing briefly the thesis that there was no Darmstadt School.

Musically, the Darmstadt School’s key figures—Pierre Boulez, Luigi Nono, Karlheinz Stockhausen—share only superficial similarities: their processes bear little relationship to one another; when they talk about one another’s music, it’s clear that they’re more or less guessing. Each does have a sort of ‘year zero’ piece or two, a sort of pure process piece, but not at the same time: Boulez and Stockhausen are doing it right at the beginning of the 1950s; Nono doesn’t get there until about half a decade later, and for very different reasons. Those reasons don’t proceed from Webern: when Stockhausen does it, he probably only knows one piece by Webern; Nono does know Webern, but he’s not interested in the number counting and, honestly, what he’s doing comes from Varèse, Dallapiccola, and fifteenth-century polyphony.

There was no dominance of serial music in any of the early years of the 1950s when people who advocated for the existence of a Darmstadt School speak of a serial hegemony: four pieces at most in 1954 and probably only two that seem anything like the strict sort of serialism. In any case, institutionally, none of them had a central position until the second half of the 1950s. Boulez essentially didn’t go to Darmstadt: apart from 1956, it was the 1960s before he really took a central role, by which time Nono was gone (and, actually, so was Stockhausen until the second half of the decade).

Importantly, the thesis that there is no Darmstadt School opposes those who insisted on its existence, either to criticise the inhumanity and facelessness of an imagined uniform modernist monolith (largely critics and musicologists, but also composers like Hans Werner Henze, whose pastel-painted Nachtstücke und Arien (1957), Boulez, Nono, and Stockhausen pointedly walked out of), or to say ‘of course, everyone else was writing these strict, number-counting pieces, but I went my own way’ (largely composers, like Luciano Berio, Mauricio Kagel, and György Ligeti). The Darmstadt School was, on this view, the invention of senior critics and administrators, with a wide variety of motivations, from curiosity to cynicism.

Jim insists, rightly, that the fact that the Darmstadt School didn’t exist in one sense doesn’t mean that it didn’t in another, and that that other sense is, itself, meaningful. At least one of the central things he posits as a unifying force is what, at heart, I regard as the dialectical engine of new music as such, a self-conception without which twentieth-century new music would not exist. This idea is simply expressed. It involves a sort of progress by dialectical nihilation: the future—and new music is committed to futurity, to this ideal as an ideal of progress—is reached by the dialectical negation of what already exists. This sort of dialectical overturning isn’t, on its own, the privileged territory of new music: up until the mid-1980s, popular music progressed through nihilation too; the reason why punk is punk is because it isn’t progressive rock.

The important difference is that punk overturns prog to become punk, while new music overturns new music to remain new music. The idea that there is a path that might be cut toward the future, that that path might be found via oppositional overturning of the known, in a forum comprised of dissenting voices, both is the dialectic of new music and is the institutional form of that idea that is (or at least was) Darmstadt.

Institutionalisation produces its own effects, though, and those effects tend to be of the form of ‘this is what we do around here’. Being part of an institution often means knowing, as second nature, what it is that ‘we do’. This has practical consequences in the Darmstadt case.

At the 1974 and 1976 courses, there were multiple pieces that performed, prominently, the sorts of institutional critique that, according to such a model, might be expected to play an important role in leveraging the future of new music. There was Moya Henderson’s Clearing the Air (1974) which featured, on stage, the massive loudspeakers of electronic music, which, on this occasion concealed real players within who cut their way out with scissors, before advancing, threateningly, on the live, visible double bassist. Henderson won the Kranichsteiner Musikpreis in 1974, returning in 1976 with Stubble, which foregrounds the female protagonist’s fruitless attempts at depilation before a date, dedicated to “all those women emancipated in the Year of the Woman 1975”. In Davide Mosconi’s Quartetto (1974–76) an accordionist is slowly wrapped in Scotch tape, and a harpist and harp covered in a single piece of close-fitting purple knitwear, making performance by turns extremely difficult and impossible. Christina Kubisch’s Identikit (1974) parodied the “precise demands of new music” by asking five pianists, at the same instrument, to play the same musical patterns at different tempi given by in-ear click tracks.

These feel to me like prescient critiques, ones which were urgent even then and yet I’d wager that they’re unknown to most of you: these weren’t the critiques the Darmstadt institution chose to support. From the point of view of the present, these pieces feel to me strikingly recognisable, like I’ve seen versions of them, or pieces performing the same sort of critique within the past ten years. One reason why that’s possible is because the institutionalisation of critique blunts, normalises the critique: when the critique which is new music becomes institution it becomes, in the same breath, ‘what we do’.

The critiques that did succeed are notable. The strongest and most potent was Wolfgang Rihm’s 1978 critique of new music’s repudiation of the tonal, a refusal which meant, Rihm argued, that new music became restricted to musical materials which used to be new: new music required the oppositional force of tonality to continue to progress. Helmut Lachenmann’s blacked-out tonalities are, in a way, the reverse face of this, a tonality which is present because it—and specifically it and nothing else—is what is refused. Brian Ferneyhough’s complexity both looked like super-saturated Stockhausen—the Klavierstücke of the early 1950s, to be precise—but also to critique them, by amplifying what happens in the friction between their seeming demands and what bodies can actually do. These three, along with Gérard Grisey, were the central figures of 1980s Darmstadt: their critiques were recognisably ‘our’ critiques. Rihm repeats Henze’s criticism of Darmstadt; Ferneyhough takes the place of Stockhausen, while criticising him; Lachenmann takes the place of Nono, while criticising him; Grisey, to be honest, is closer to Stockhausen than he is to Boulez, but as metonymised, with Tristan Murail, in the institution of Ircam, they seem, in the Darmstadt context, to be his emissaries. These 1980s factions were as entrenched as their forebears: spectralists booed complexity; neo-romantics were scathing about musica negativa; Ferneyhough complained about tribal warfare while engaging in it. And yet, the endgame was already known: once institutionalised, because new music is critique, the critique is institutionalised too, and some critiques are the sorts of critiques which ‘we do around here‘ and some aren’t. What happened in the 1980s was, on one level, not a revitalisation, but a re-run of new music’s greatest bust-ups.

In the 1970s, the institutionalisation of new music at, and as, Darmstadt meant that the sorts of critique which seem now most potent, most urgent were the ones that were ejected and it took another forty years or so for new music to get back to them. Worse, by the time it did, those composers—those allies—weren’t around anymore. New music is critique, yes; Darmstadt is the institutionalised form of that critique too, yes. But when critique is institutionalised, it becomes easy for the institution to favour ‘critics like us’. New music requires new critique.

Patrick Becker:

It’s a pleasure to be here today, not just as a publisher, but as someone whose previous life—before ISBNs and warehousing—was immersed in precisely this kind of discussion. In that sense, returning to Darmstadt for this panel feels less like a marketing obligation and more like a minor resurrection—though, I should add, without a gravestone.

We at Wolke are delighted that Jim’s book arrived just in time—literally at eleven o’clock this morning. It means that we can speak about it not just as an abstract idea, but as a tangible contribution to the ongoing conversation about critique, history, and the role of Darmstadt itself.

The title, What Was the Darmstadt School?, already raises a host of questions. Did such a school exist? If so, what defined it? The temptation is to reduce it to serialism or to a certain aesthetic orthodoxy. But this view seems difficult to sustain—especially in light of the intense individuality that characterized so many of the musical works created in the 1950s. It becomes problematic even to speak of a unified “style.”

If the Darmstadt School ever existed, I’d suggest its true character lay not in compositional technique but in social practice. Darmstadt was—and in some ways still is—a place of convergence, a space of encounter. Here, people behave differently. Discussions emerge. Creative labor is laid bare. There is a kind of grassroots openness that remains unique—where the simple act of engaging in dialogue can serve as a beginning, a “first stone” cast into the pond to watch what ripples might emerge.

One of the striking claims in Jim’s text is the extent to which today’s musical institutions—Darmstadt included—have become entangled in the mechanisms of the culture industry. Applications, commissions, and reputational economies increasingly define what can be done, who gets heard, and which kinds of critique are permissible. But I hesitate to frame Darmstadt as simply another outpost of this machinery. Between Darmstadt and what we typically mean by “industry” lies a vast expanse—miles and genres wide.

Of course, there is an ecosystem here, one with its own hierarchies and gatekeepers. But I would argue it is still a distinct one. Unlike the wider industry, where criticism is largely subordinated to promotional logic, here we still occasionally catch glimpses of friction, contradiction, and—yes—hope. That we are having this conversation in an unadvertised panel, yet in a full room, is proof that word of mouth and genuine interest still matter. No algorithms required.

For me, the most generative dimension of this book is not the historical analysis alone, but the insistence that the question of the Darmstadt School has bearing on the present. The histories we inherit are already interpretations—layered decisions about what to highlight, what to omit, what to mythologize. It’s worth reminding ourselves that even “factual” history is shaped by the narratives we choose to believe.

And that brings me to a central point: If we continue to frame the Darmstadt School as something that was, then when exactly did it end? When did it “die”? And who decided? Why do we presume it belongs to the past, rather than seeing it—perhaps uncomfortably—as part of our present? If the question is no longer “What was the Darmstadt School?” but “What is it?”—then that becomes a call to action. Because we can still choose what kind of institution we want this to be.

Finally, one concern I’d like to raise is the disappearance of aesthetic critique from public discourse. There was a time when even Die Bild-Zeitung felt compelled to mock contemporary music. And while their derision may have been misinformed, it was at least grounded in a listening experience. Today, we are seldom critiqued at all—neither from the outside nor within. It’s as if we’ve ceased to be threatening enough to provoke anyone. That, to me, is more alarming than any bad review.

And since we’ve just been reminded of the all-too-familiar gender imbalance in our field, let me conclude by pointing toward another kind of resurrection: tomorrow we’ll present Juana Zimmermann’s dissertation, a work that reconstructs the often-overlooked presence of women at Darmstadt between 1946 and 1961. Her research reveals that they were not absent—but systematically erased. It’s a vital reminder that history is not just what happened, but what we choose to acknowledge.

So yes: critique matters. History matters. But so does our ability to shape both—together.

Steven Kazuo Takasugi

Two anecdotes!

First anecdote: One year, a friend reported to me that he had a conversation with a young composer here at Darmstadt, sometime in the aughts was it? She told him, “I want to learn Complexitist style of composition.” He queried back, “Why do you want to learn that?!” She hesitated and then confessed, “Because my teacher said it wins competitions.”

Second anecdote: One year, I heard someone say something that I’ll never forget. It might have been in the teens. It was very simply stated, though one can and perhaps should analyze the motivation for such a retort. It was stated: “The concerts in the Open Space are more interesting than the concerts on the official program!”

Firstly, I don’t claim any scholarly expertise on the history and culture of the Darmstadt Courses over the decades. You can consult those experts here. What I can claim, though, as a fact is that I’ve been an avid participant at the festival since 1988. My understanding of this institution therefore is informed by personal experience. I observed the festival under the directorship of three very different directors: Friedrich Hommel (1981-1994), Solf Schaefer (1995-2009), and Thomas Schäfer (2009-current). I might very curtly characterize the very different organizational styles of the courses in this way, each with its advantages and disadvantages: Hommel: utterly chaotic, but then anything might happen; Solf Schaefer: to rectify the chaos, organized, perhaps too organized, so the question arises: “What happened to all that great spontaneity?”; and Thomas Schäfer: a balance between organization and chaos, the organization framed via the official workshops, the chaos “framed,” corralled through the Open Space classrooms.

Now, the Open Space events are not announced on the official festival program. But does this mean there’s an implied hierarchy of importance given to the different event spaces at Darmstadt? Then Open Space, as a possible grassroots, subversive, outsider institution within an institution, is subject to a second-class status, which is quickly noted by all the young, aspiring musicians here: the system is rigged, how do I play the game, how do I become official, in other word, as our first anecdotes uncandidly reveals, “How do I win competitions?” to further my career back home. But my second anecdote, that the events in the Open Space are more interesting than the events on the official program, begs the question, is another scenario possible?

One last short anecdote: Two of us, Martin and I, were for a stint board members of the Eiler Foundation. The Eiler Foundation financially donated to IMD and supported the Staubach Prize for composers here at the festival. When that was terminated, the question was asked of the board to recommend how the monies should be spent. We agreed that it should go to the Open Space project, specifically to remedy any lack of outdated equipment in these spaces. Although this too was eventually terminated, the idea was spawned, that the Open Space institution…if supported from outsiders…with smart planning and strategic financing, could acquire something more than a second-class status. And this planning…might I say scheming…could subsequently sustain a community of like-minded individuals over the gap between festivals…a nice byproduct of collaborative effort.

Thus, in the spirit of the tradition of critical thinking and social analysis and organization, I suggest that Jim’s article is this generation’s “call to arms,” and that a society grow from this moment, inspired by the past, to lift Open Space as an institution within an institution, legitimate, respected, alternative in the best sense of that word, and vibrantly critical, and directed and determined by the participants themselves as Jim writes! [Holding up the book.] This, my friends, is a manifesto. When my dear friend Claus-Steffen Mahnkopf publicized his and Mark Andre’s “Dekonstruktivistisches Manifest” in 2002 at the Munich Biennale, Brian Ferneyhough quickly knocked in down saying, this was not the time for manifestos. A call to arms is a manifesto and we need one more than ever today, in these times.

It would make sense that such a society be comprised of musicologists and music journalists, writers of critical thinking on music, but that composers and interpreters be just as essential. Open Space was designed with Hommel’s creative chaos in mind, that anyone coming in for a few days during the two weeks could create an event. Few have understood this opportunity to the fullest extent…until now, say with Visite Critique, its discussion groups of concert criticism and review. Who here knows about Visite Critique in the second week here?

This might be extended to include debate panels such as the Darmstadt Forum that Ash Fure and I set up a decade ago, but also other opportunities to voice constructive critical opinions on our activities, both spoken, written, but also creatively imagined in say concerts and installations. One that has been suggested by Elaine involves films by Mauricio Kagel, Alfred Feussner, and Ursula Burghardt, utilizes television reports, and gathers a mountain heap of outdated technological equipment alongside the reading of musicologically excavated texts and correspondences. This is really exciting to me! Needless to say, this society and its activities would require realistic backing (need-based travel and hotel subsidies for guests, some equipment but really not much, installation objects and their storage and delivery, guest speaker honoraria perhaps, website support). It’s quite doable with a two-year gap between festivals.

A call to arms is a call to action. That is what an activism best achieves aside from talk. What do you all think? Any joiners?

Thank you.

(photo: IMD and Kristof Lemp)

Elaine Fitz Gibbon:

Thank you all for sharing these thoughts, this rich material. I now have the daunting task of responding in some capacity to your four voices! I hope to offer some thoughts on what I think are many moments of overlap, and a few questions as fodder for further discussion. Throughout these four presentations, I believe we can trace a golden thread of a few, perhaps obvious, key terms: institution, institutionality, and their strange histories. Institutions, unsurprisingly, for where are we, of course, but sitting in the (borrowed) classroom of one of the perhaps most internationally well-known contemporary music festivals, a position that this institution has held for what sometimes feels like its nearly 80-year existence. Its reputation precedes itself.

Yet, Patrick, Martin, Steve, and Jim all have spoken to the strange distortions that this reputation has caused in attempts to articulate the Ferienkurse’s historical—and perhaps more significantly for the topic at hand today—contemporary significance. In his remarks, and his brochure/essay, Jim portrays for us a kind of golden age: a time in the hazy, distant past (70-odd years) when public, and fierce, intellectuals like Adorno participated in the institution without feeling the need to be beholden to a curated image or self-perception. This well-rehearsed story is one with which we might feel intimately acquainted: a bedtime story, a legend, a myth. Martin cautions us, however, to look more closely at the chain of telephone lines that passed that story down, and what got obfuscated—purposefully or otherwise—along the way. The work of Moya Henderson, Christina Kubisch and Davide Mosconi at the 1974 Ferienkurse asks us to reconsider those traditions, and lines of critical influence, which have been written out of the typical Darmstadt-School-focused narrative of this institution’s history. Yet a (relatively) easy glance through the archives—located not too far down the road from here, attests to the presence of this work, these individuals, and the vocal critique uttered by composers, journalists, and musicologists – as well as publishers, I’m sure – from ca. 1968 through the mid-1970s.

And as Patrick points out, the ideologies that drive the preservation of certain narratives—be they critical or not, be they articulated in the yellowing pages of bureaucratic correspondence or in the whispered conversations between friends on the steps of the concert hall—are inescapable. Beware the siren call of those arguments that would suggest otherwise!

We hear a different side of institutional history in Steve’s opening anecdotes of a kind of whisper network at the festival, which caution us archivally fevered historians to not put our entire trust in those official documents. They continue, after all, to be curated by the capital-I institution itself, das Internationale Musikinstitut Darmstadt (IMD), unlike many other festivals whose papers are deposited in local, city archives. And Steve likewise reminds us of the pressures of financial instability and anxiety that drive composers (and one might add performers, music journalists, festival organizers, and music historians…) to admit to desperate acts of self-preservation—particularly as populist politicians, in gleeful spectacle, pick and gnaw at the long emaciated carcass of public arts funding, something with which obviously we are confronted more existentially today than back in the aughts of Steve’s anecdote.

Through these different perspectives I hear a desire to lend an ear, and voice, to different histories—which, as Jim’s text latently suggests, I think, might point to brighter futures. I hear in these critiques, and in a groundswell of recent musicological attention to the weird—and in fact emotionally fraught—narratives that we were fed about the history(ies) of modernism, and therefore Darmstadt, during the strange decades of the 1980s, 1990s and early 2000s, a desire to free ourselves from the blunt instrument of caricature that has been used to write those narratives.

So I have a few questions to start off our discussion:

What is at stake in thinking about the Darmstadt School today? Why does it matter? Why should we care today?

Each of you is active in different capacities in new music, as composers, academic music historians, as publishers, journalists, dramaturgs, and teachers etc., and for many of you, you wear not just one, but many of these hats. So I am curious to hear how you view the role of “critique” in your everyday professional lives, be that here at Darmstadt, or elsewhere.

- How do you define (for yourself individually) the practice of critique?

- What does critique mean or look like to you?

And similarly, how do you view the role—and practice—of history (big or little H) in your own work? (in concrete terms)

- Who gets to participate in writing its histories?

- And where does historical knowledge figure in a practical sense?

What is the relationship between critique and the writing of history?

- Who, historically, has participated in the practice of critique? And who gets to wear the hat of “critic”?

- Has that changed over time?

What does hope look like at Darmstadt? Why have—or, according to Jim, not have—hope?

- Where, in what, and in whom do we find hope?

- And what, materially, does or might that practice look like?

Martin Iddon:

Perhaps I’ll start, given the fact that I’ve written a book that focuses on the history of the Darmstadt School! I can reflect on why I wrote my first book in the first place. And the reason was because of the history that had been handed to me. Things like reading yet another analysis of Structures that tells me, “this is what all the pieces are like.” And then going and looking at them and realizing that they’re not! I mean, aurally, Structures and Kreuzspiel are very different. If I hear Kreuzspiel I hear Milt Jackson, I hear the Modern Jazz Quartet, and I do not hear that in the Boulez. And so part of me was just going, I just don’t think that this history is true. I don’t think that the thing that I’ve been given by the previous generation is true. And in some ways, given that I started off as a sort of father-murdering musicologist, then I absolutely deserve to be cited in Jim’s text occasionally, in a way in which Jim overturns a whole bunch of the things that I said as well. And that is also a really important part of history writing. And speaks to the ways in which this history can be rewritten, and that comes to the second point.

My wariness of institutionalization is that we think with certainty that this is what Darmstadt is. But I’ve been coming to Darmstadt long enough to know that Darmstadt has been many different things. Maybe not as long as Steven, but my Darmstadt, as a young composer, is the one that has studio concerts at the end. That begins with everyone fighting violently, composers fighting violently, over performers, because if you don’t get them by day two, you’re not going to get a gig in a studio concert, and you’re not going to win Kranichstein, and all of those things.

And I’ve seen that shift radically. And yet, there’s still a bit of me that goes: that’s still my Darmstadt. So that sense that it changes really quite radically, and of course most people come through relatively briefly. So you will come and have your Darmstadt, particularly if you come here, like me, three times, then you’ll think: “That’s Darmstadt. That’s what it was.” And it was, but it was also a lot of other things as well. That’s why I mentioned people like Mosconi, Henderson, and Kubisch – and I could have talked about many others – because, from my point of view, the institution has been so many things that we can make decisions about which one of these histories we want to matter to us. And that’s partly to do with what Jim was saying as well, that this history has been so fraught and has meant so much, that you can go back and say, no, look, these things did happen, these are the things that now I think matter. And the sense, that force that says that history is given to us, can be leveraged against itself, because we can be wrong and we can take interesting, cool, useful things out of the past. In many ways I think that’s the reason why many of us write history, because you want to go into the past and find cool stuff.

[Addendum to the transcript by the editors: Martin Iddon: „… and cool new music. I see Michael [Rebhahn] sitting here, remembering his text I hereby resign from New Music, which…“ – Jim Igor Kallenberg: „…which he didn’t…“ – Martin Iddon: „…oh no – none of us does. But that was the point I want to address.“]

That’s the power of rewriting history: to extract meaningful, interesting, useful things from the past.

That’s why I care about writing history. It’s an opportunity to excavate the cool stuff from the past, and it’s nothing much more than that. And I come here, still, so I get to hear some cool stuff that I wouldn’t get to hear elsewhere, otherwise. And the past is full of it, too. And I’m interested in the music because I want to hear these things that I don’t yet know.

Jim Igor Kallenberg:

So why is the “Darmstadt School” as a historical object important to think through in the present? For me, it’s really to get rid of history, it is necessary, unfortunately, to deal with it, and to work through it. I don’t know if there are any English-speaking good Marxists in the room? But there’s this quote from Marx, where he says: “The specter of all previous generations weighs on the brains of the living.” And I think that this is the problem with the Darmstadt School. I think, how we see the past really limits the possibilities we see in the present. And if we reduce the Darmstadt School to a positive, single compositional style, then Darmstadt becomes history. So we can’t ever experience Darmstadt as something alive and present that we are to shape. But we will see it and experience it as an historical object that we have to live up to, or that we have to follow, or legitimize our activity through. And this is what I think happens, in both ways. In either saying, there was a Darmstadt School and it did this and this, giving it a positive content, and also in the opposite way, saying, No, there never was such a thing, also thereby giving it this positive content, but rejecting it, and rejecting any authority then to really experience, deal with critically, and so on, new music. So I think that working through the way that we see history is in fact a way that we see the present, and I think that this is something to be worked through. Because, why should we even see possibilities in the present and learn from the past or work through the past? This is an educational space. But the question is, what do you learn here? I’ve talked to a lot of composers, and what do you learn here? You go to two sessions; you write it on your CV; you do everything to get a performance or a prize, etc. to have an audience here, to have a platform here. I don’t know if it’s true to the children who learn here, to tell them what is told about the history of the Darmstadt school. And I think that this is the only duty, of why we have to deal with this stuff of the past, which I would like to be free of.

Patrick Becker:

I’d like to add two things: First, that the idea that we need to deal with the history of the “school” is important, but the history itself is already what has been written about it. So we are not directly dealing with historical musicological sources, but with the decisions people made about how to interpret those sources. So of course we have a great deal of secondary literature that tells the history of the Darmstadt School. It doesn’t need to be that institutionalized and that academic, it can also be, for example, anecdotes; it doesn’t have to be written down, it can be passed down orally. But there is a decision based on facts, so to say, which are also not neutral, on the histories that are told. There are already several histories of Darmstadt written by authors, interpreting the same sources in a different way. And I would say that we can try to work through those not really neutral facts, those stories, by looking at the music of the 1950s, looking at the documents from the 1950s, and coming to our own conclusions. And this should also happen aesthetically, to evaluate what kind of music was played there, both in the score and in the sounds that resulted, which we can hear thanks to all of these recordings in the archive.

The reason why we need to engage with this history–or engage with the past, to use another word–is because it still matters. Otherwise we wouldn’t be sitting here. If we would have forgotten about it, no one would come here, and we wouldn’t be sitting here, and you, Jim, wouldn’t have written this book.

The other thing that I find very interesting, which I don’t think we’ve talked about thus far, and which occurred to me while reading, is: the book is called “What Was the Darmstadt School”. When did it end? When did it die? If it wasn’t serialism, then when did that stop? Why do we assume it’s in the past? Why do we not think that it is part of our present? If it is part of our present, then the question would be: What is the Darmstadt School? And that’s the call to action, because we can decide that.

Steven Kazuo Takasugi:

From a composer’s point of view, why is the past, why is a critical compositional past so important? It’s very, very simple: I want to be challenged. I don’t want my art work to be self-satisfied and complacent. That claim is a very strong one, but I think it’s a very important one. I come from a culture that doesn’t like so much criticism — especially in music and in art. Well, maybe less so in art, but particularly in music. It’s again like I said this morning, “I liked your piece, and we’ll end it with that.” But we’re so hungry, I’ve seen many young composers throughout the decades who are hungry for criticism. They don’t just want the, “Oh, I liked your piece.” They want some vigorous kinds of things to think about. And what is that, when you’re a composer? It’s really awareness. Self-awareness. Why? I think that when we create, we want it to be really good. How does cool music appear in the world? Probably usually because someone has tried to make it good. And so, I think criticism, or critical thinking, will really help us – cognitively, physically, emotionally, expressively, intellectually – expand our horizons and get us out of our comfort zone. And that’s just such a challenge. And so the Darmstadt School, this critical tradition that we’re using the Darmstadt School as – and there are other traditions as well, but this one is particularly strong, I think for many of us, is inspiration to remind us that some of our predecessors did really hard, arduous thinking and examination. And I think that’s really inspiring. They raised the bar very high. And so for us, I think that that’s not a challenge we want to evade and find another way around, but maybe go through that critique, and also critique the critique. Critique ourselves. So I always say: Self-criticism is the best kind of criticism. And I think the Darmstadt School really provides a way that music can do that. So that’s why I think it’s important.

Open discussion:

Seth Brodsky:

I’m very glad, I’m dying here with thoughts. I’m very, very, very appreciative to you for creating this, for prying open space. I’m sorry that I showed up a couple minutes late, so I didn’t hear the beginning of the account of why this wasn’t officially scheduled, but that’s wild, that’s kind of crazy, but I’m enjoying this Streisand effect.

There is a bigger question: why critique? Nobody actually answered that question. There was “New music in order to stay new music” – it is a beautiful formulation, that Martin had – “has to critique itself.” Critique is necessary for new music to remain new music. The question is just: why does there need to be new music?

The specific thing I wanted to hear more about is not just history, but historicity, because in some ways it felt like after 2001, after 9/11 history is rushing back. We are at the end of a period of about two to three decades, of what people generally have conceded as a kind of end of history. And history comes rushing back. But in fact, there is a lot of incredible decomposition that we are seeing world over happening now, in which critique is completely besides the point. We are talking about the obscenity of raw power and the dismantling wholesale of institutions, an understanding of a part of the right that if you dismantle the institution, then critique doesn’t matter.

With all of this, we’re foisted back into some terrible new version of postmodernism. And I’m with Fredric Jamerson here, the problem of postmodernism was that we were losing the concept of history, we’re losing the capacity to even think historically. And only thinking historically provides the ground for the kinds of attachments to the objects of the past that allow us to critique in the first place.

In some sense I think that Jim is saying that: we have to be attached to the past to fight it. And what we see now is that, and yes one symptom of it may be a kind of careerism, that says “I don’t know what the past is – Everything I’ve learned, I’ve learned from Score Follower from YouTube – It’s a weird canon, it might have also fallen out of a plane into a field”. So, there is that sense of lack of history, but also with historicity comes attachment. And you’ve all spoken in wonderful ways about your attachment, it’s a libidinal thing, it’s an erotic thing, an unerotic thing, also maybe a neurotic thing. Can you talk more about this?

Martin Iddon:

I’ve got a very small answer, and I’ve got a larger answer, and it might be the same answer. I think it was Steven, who talked about what he actually learned here. I had earlier talked about the cynicism of this. I had maybe three composition lessons here, that had been entirely lifechanging. And those things have been a product of critique, proper critique, the sort where you’ve got a lesson and you’re terrified, because you know what’s going to happen. And those lessons, when it’s done with love and in my case, it always was, were completely brilliant – hosed down and then forced to look into the mirror about what I’ve done. That critique on a personal level of what whoever I might be as a composer and yet I am committed to that thing. There is that personal thing

The bigger answer is, new music doesn’t have to exist, new music didn’t used to exist. It is really easy to imagine a world that doesn’t have new music in it, that’s straight forward, speak to most people you know. [Interjection: It doesn’t exist] We don’t exist. Which is to say, the reason for this critique is, because I do think that critique is the very basis of what this music is as distinct from other musics. That dialectical motor combined with the idea that we remain new music by destroying ourselves is what we do, therefore without that we can’t have new music. The sole commitment is that I remain profoundly in love with new music. And I presume that everyone who is involved in new music is at some level involved because at some point in your life you have heard a thing and went “Holy hell, I didn’t know music could do that.” In my composition teaching as well, I will just tell you a lot of stuff, because I really hope that somewhere in here you will hear a thing and you will go “Oh, that changes things”. It’s a gamble, absolutely. My big answer is critique because I believe in the gamble.

The other version of that is that critique is under threat in all sorts of ways and it seems to me that it produces the thing that I love profoundly, so I want to keep defending it.

Seth Brodsky:

That’s very helpful to me, because one of the things it articulates is the distinction between a critique that faces outward – which of course any can, and something can double as out. But this is a critique for the sake of an existential situation. That’s very different than survival instinct, but more like a survival desire or survival drive. Survival instinct is careerism. So, I think there’s a very interesting articulation here.

Martin Iddon:

I think maintaining the word love that we don’t tend to talk about very much, because it’s embarrassing in all sorts of ways, is still the important word.

Steven Kazuo Takasugi:

Especially the “I didn’t know music could do that.” That’s actually what really inspires me. So, I think it’s exactly the exclamation that “I didn’t know music could do that.”

Martin Iddon:

But I also don’t want to make new music special. It’s just that I know lots of people who have had that experience to it. But if you have that experience listening to Pantera or Taylor Swift, then terrific. I just want you to have that experience. But this seems to do one that those other things don’t do.

Audience:

I think you need a more expansive understanding of critique as an opening to all the different ways music can be. The problem here is that it’s a little bit navel-gazing with the way you’ve got it constructed. So, for example, think about: “Thank you for that beautiful concert last night.” I would draw in Han Bennink and Sengyo Kumizo and juxtapose them to have a conversation about the extent to which composed performance is something that’s part of the practice of beautification that lasts 40 years. The way in which the beauty of the flat is something that’s inherent in classical Japanese music and that orientation to an expansive understanding of music in the world is the way to deal with the crisis that you’re articulating. I mean, critique for Adorno in 1950 is imagining a world that just does not exist anymore.

Why you would critique, what your goal was in critique in that period, it’s just not where we are now. So, for example, one thing to give critique, I’d say I think sedation is more the issue now than, um, individual crisis. I’ve seen many pieces that in a sense they’re referencing expressionism, and I think that has nothing to do with what happens when somebody is on their phone all the time. It just doesn’t. Yet that’s the cultural problem. One piece of this is a much more expansive canon, a constant expansion of the canon to that which is not part of new music and see how it can allow music to be different. Not asking to do the same, but just to recognize what’s in there. And the other part of this is to recognize that history reflects a self that has changed undeniably and to ask the question of how is this self different now?

I’m completely devoted to working art. I mean, I do this on David Tudor all the time. This is very important, right? There’s no question about that. But it needs to be in a dialectical relationship with the world and the present and right now, the way you’ve got it narrated kind of erases that a little bit or attenuates that. I think the real issue is that that needs to be brought forward more.

Jim Igor Kallenberg:

Both of you raised that we didn’t say what critique is or that it’s underdetermined. I really determined it, and I said it’s what is necessary because artworks aren’t clear anymore in what they mean and what kind of experience they invite us to. So, they must and can be interrogated. That is critique. It’s in the ways they can transform our experience and even our capacities of experience. That’s also what you both said, that is interesting in new music. When you hear something, listen to something that you wouldn’t know, you can just be disturbed.

Like you, I don’t think that this is reduced to new music. I think probably the capacities to do that transformative experience, or even transformation of the ways we can essentially experience the world, that maybe even the bigger, more industrialised genres of music today can do that better. Because I agree with you [probably Patrick Becker], you said “This is not an industry. Look at Darmstadt, look at the tables we sit at. This is an industry?” No, of course it’s not. But I said in my opening statement that the situation is even more restricted. We are a state-protected pity craftship. Really! Because this is much more narrow-minded than whatever economically well-situated industry in the realm of music.

It is not only new music who can provide this experience and which needs criticism, but it is really the raison d’être of new music. So, if new music cannot do this, then really it’s just some people wanting a job because they can’t get a job in another field. If it’s not for that experience that both of you [Steven Kazuo Takasugi and Martin Iddon] agree to.

Audience:

Duchamp made the point, he said, „Well look, as an artist, you’re basically immediately you have no control over how your work will be understood.“

Jim Igor Kallenberg:

Of course, you transform experience with pieces. With art you can transform experience, and if you get rid of this, then don’t do art.

Max Erwin:

I just want to build on what Seth was saying. He was asking, “why critique?”, I’m interested in “where critique?”. It got papered over, but I think Jim and Patrick had a radical disagreement there about the position of Darmstadt. It sounds like Patrick was more or less advancing an idea of an autonomous art, an art that is separate from the culture industry. And Jim said, “No, no, no, this is the loneliest shittiest alley of the culture industry.” [Interjection Jim Igor Kallenberg: The pitiest department of culture industry is here, not an exclusion of it.] It seems like the thing underlying that is this idea of autonomy. So, when we’re in this position, where is the critique coming from? Is it necessarily always already within this ecosystem and a kind of echo chamber, or can we have a voice from outside of new music critiquing new music? Is that even possible?

Patrick Becker:

I would say it’s completely within the ecosystem and that’s a bad thing. I think the days were better when media like Die Bild would critique contemporary music because they would do so not for institutional reasons, but for aesthetic. And now there is no aesthetic critique any longer, especially not from the outside. From the inside, this is something else. But even then, it’s more about the institutions and so on and so on. Where is the critique in words and writing – I know nothing was better in the past – but of the level of the past? It’s very sad that Die Bild doesn’t attack us every day. They should. But maybe it’s our fault because they don’t perceive us as a threat.

Max Erwin:

But that’s across music though. I mean music reviewing. Pitchfork just got bought by Condé Nast, no one’s even reviewing pretty mainstream pop music.

Patrick Becker:

The critique of Die Bild Zeitung essentially said, „Oh my God, you can’t listen to this. It sounds like someone having a stroke and playing a synthesizer.“ At least they build it on their listening experience, not on discursive power and people being excluded and so on. Which is extremely important. It was wrong back then not to talk about it, and it’s wrong today not to talk about the aesthetic side.

Jim Igor Kallenberg:

You [Max Erwin] made it a controversy and said that… [Interjection Patrick Becker: We go outside then; Laughter] we have an opposite point. I think it’s not necessary to be part of the institution or not part of the institution. What I say is this institution was founded with ideas that should be the organized self-criticism of music history. The organized self-criticism of the people who produce and reflect music history. And this changed. It’s not anymore.

So, what is the place for criticism? Academy is organized, the industry is organized, promotion is organized. Criticism must be organized! If it exists and where it exists is the question of the self-organization of the people who want to deal with new music on the terms of free aesthetic experience instead of terms of promotion, jobs, marketing et cetera. You need both. You also need a job, of course. Me too. But you can engage in activities that aren’t about that, and you can also engage in activities that are about that. I think you should just separate it and organize it, but I’m really not here to give hope to anyone. I did it for 10 years. It seems very impossible to me in my experience.

Audience:

Paradoxical maybe. It feels paradoxical. We have this kind of critical thinking and the music through critique, and by in turn doing the musical critique, it becomes the norm in the institution. It’s like a constant cycle of this nostalgia.

Jim Igor Kallenberg:

It’s not, it’s not. It’s a question of the independent organization of people that are interested in the music on its own ground on the experience it produces instead of being interested in a job. And sometimes it’s hard because you can’t say what you want to say if someone’s in the room who… I know!

Audience:

So you don’t think it’s paradoxical at all?

Jim Igor Kallenberg:

It’s a contradiction, but you have to either organize it or you just run on the train with your career being pushed forward, hopefully.

Wieland Hoban:

I just have three observations. The first one is the main point as it relates to the actual text under discussion. And that’s, obviously, the title is what was the Darmstadt school. But what’s implicit in the entire text as a premise is that, whatever Darmstadt is now, is inadequate compared to it. And that in the old, there is something that’s been lost that we need to somehow recover or reinvent and reconnect with.

And because of that – even though the framing is, whether this was the Darmstadt school or not, however one might view it – I think the now remains kind of underdetermined because it’s kind of taken for granted. Okay, things have kind of gone to shit now. I don’t have to argue that point. That’s my feeling, that you kind of evaded the task of backing that up and that I feel that there’s a kind of imbalance without some kind of specificity because you get very specific about some of the old things. But then you don’t really mention anything that’s happened in the last 20 years, other than generally saying, there’s been an act of this and it’s sort of degenerated into that, but there’s no real specificity.

Slightly less fundamental observations, Steven, what you said about giving a bit of an institutional boost to the alternative program. My instinctive thought there – I don’t know if you will share it – is that this kind of risks turning the alternative into the institutionalized part. Like the footnote that encroaches on the main text, which happens quite often in the text [Interjection Jim Igor Kallenberg: Which happened here, I admit].

And then just finally, a small observation on what Patrick Becker said about the question of, when does the was end? Where does the present begin? What is the cutoff point for the past tense? And in my view, the cutoff point comes because nowadays, we no longer think in schools in the same way that we used to. So, the very concept of the Darmstadt school, there’s a historicity to this way of thinking and that nowadays people don’t think, „Is there a Darmstadt school?“ I don’t know if anybody would ask that question nowadays just because it seems outdated, an outdated thing, outdated way to think.

Patrick Becker:

Me, because I also thought about this when I read your [Jim Igor Kallenberg’s] text. I think this is something very historical musicology like, coming from the sources. I think we have to come up with a notion of school in the concrete case of Darmstadt, because you also go through some literature and different concepts of schools and music history. I think it’s a top-down approach, which is not the right way to do it.

I would say that we have to really understand what was the Darmstadt school – not school, but Darmstadt is the focus because there’s something very precise. I’m not saying that we would reach a result with it, but I think this more or less everyday understanding of school probably does not apply, also a more scholarly approach of school does not necessarily apply. And one of the reasons why there are so many of those texts on the Darmstadt school is because they try to find out what it is.

You also mentioned it in the text, they’re always in quotation marks and I think your argument is they’re in quotation marks, because they try to avoid the problem of this term. And I think the quotation marks raise the point that this is super problematic because we don’t really know what it was.

Jim Igor Kallenberg:

So, people should not talk about it. If it’s so problematic and it’s really nothing, why don’t people stop talking about it? My first two quotes in the book are for you, Martin, because two texts of his really just make the reason to write it in an academic way.

The first is something that is also true with your [Wieland Hoban?] question about the present. I avoid a lot of stuff. Most of all what I avoid is music. Martin Iddon really worked through the whole thing analytically. He really showed in musical analysis that there is no ground for a positive programmatic serialism style of compositions. This essay doesn’t even touch what should be the object of critique – music. This is avoided. The present is avoided too for other reasons, because it is a study of its own.

What I only do – and this is also where I object to what you [Patrick Becker] said about top-down – only let speak the voices of the people who thought they could constitute a Darmstadt school. It was an idea of them, not even a reality of them maybe. Maybe they didn’t even succeed constituting a Darmstadt school or building that institution or that context that they wanted to build, but it was an idea.

And that is the idea that is repressed in the present, and this is the only reason why I wrote this to remind us that there was an idea that is repressed today, more it is not.

Steven Kazuo Takasugi:

You’re absolutely right. That which is outside somehow slides right back into it, but that’s just as seemingly natural process of the aging process, right? So, a forum like this is about being aware, critiquing whether or not we’re becoming mainstream or institutionalized, and that claim of being subversive, or radical, or outsider, or marginalized needs to be constantly reassessed in discussions and debates.

Otherwise, what else is there to do? I mean, either stay at home, don’t do anything. See, that’s the alternative. Oh, let’s just not do anything. That’s my problem, that stay at home. Let’s not talk about anything. We’ll just go along.

This is an attempt, and the danger is that this critique will slide back into real life. We need to constantly be aware of that possibility and for people to come in and offer their criticisms, as well as fresh perspectives.

Assaf Shelleg:

Jim, the more I hear you, the more this meeting feels like a rebels’ gathering in Star Wars. Still, I want to breifly talk about two things in regard to critique and call to action. To begin with, we agree Darmstadt is a monolith, it’s not a school, but there is a sense of centricity here that I think should be avoided. This top-down approach isn’t useful here because if we keep reverting to the ’50s and ’60s, we would be ending up with the same figures.

And in fact, if you look at the curation in Darmstadt over the last two to three meetings, you’ll notice that composers talk about their work, while musicologists discuss the classicists, so to speak—Berio, Maderna, Stockhausen, and company. Nothing in between. Martin [Iddon] and I were trying to counter that here with a variant of public humanities, public musicology. We were rejected, politely but brutally. [Interjection Martin Iddon: It was very polite] Yeah, but in a passive-aggressive manner.

So instead of this top-down approach, I’m thinking about the music that we’ve been hearing here for some years; and I see a young cohort of composers for whom the difference between a citation, a paraphrase, a meme, a translation, a simulation, or a sampling is simply nonexistent—as is the difference between truth and falsity. And Indeed, truth has become a genre over the last years.

So, maybe the other approach, instead of continuously and obsessively centering Darmstadt of the ’50s, even tough we keep saying it’s not a school, would be to diffuse this monolith by working low and slow: by looking at speficic compositions and composers, moving from one object to another. And if all this is thick enough, we’ll have enough to write about, without zooming out to generalities. And on that note, I want to call here to people to use the Partisan Notes platform and write something for us—whether it’s 1,500 words or 15,000 words. Just do it.

Jim Igor Kallenberg:

I totally agree. Get rid of the history and deal with the art really and your experience with it. Thank you.

Leonie Reineke:

I don’t want this to be the last remark. I just want to share an observation in order to make sure that it doesn’t remain invisible. I have recognized that the number of the male people on the panel, very much equates the number of the male people in the audience and also the number of people speaking here. I didn’t want to judge or something, but I just wonder why that still is or again or… yeah, having discussed that topic critique, your critique.

Patrick Becker:

Thanks, Leonie, for raising the point. It could have been one less, but here we are. I would say that, just to avoid the impression that we are trying to create a male autocratic state of criticism in Darmstadt, as an alternative, what I can offer from the side of the publishing house is to come tomorrow at 2:00 PM to the wonderful book presentation of Juana Zimmermann’s dissertation, which is in German. But the topic is still relevant because it deals with all the women who were in Darmstadt from 1946 to ’61. A period noteworthy for allegedly not having any women composers there despite that there are 454 people in all the participant cards. And this dissertation is actually dealing with those women, presenting many of them in detail and also having a full database that will be available in the archive of the IMD to raise the awareness of this effect. I mean, from the panel programming and us sitting here, I totally get that, and it’s very good that you raised this point. We don’t want to let this go unmentioned.

Jim Igor Kallenberg:

I just object to my position being framed as male.

[This remark has provoked some confusion in the aftermath of the discussion. Here is a comment by Jim Igor Kallenberg: „I want to make clear that in my objection to my position being framed as male I did not refer to my gender but to the position I articulate. I think it doesn’t push a male agenda and I think it can be engaged by anyone regardless of their sexuality.“]

Martin Iddon:

And in terms of institutionalisation, this is why I wouldn’t want to get rid of history, because the history is what tells us that this is exactly what’s happened and what continues to happen. And I did put Maya Henderson there for a gentle Darmstadt reason, which is at the point at which she won Kranichstein, that was the first and only time in the history of the prize when the prize-winners had been gender balanced. [Interjection: In 1974] In the second year of awarding. It has not happened since.