WHEN FATE CROWS AND NOBODY CAN HEAR IT

This text is an edited transcript of a radio production by the author for Radio Frankfurt, first published as text in German in MusikTexte 166, pp. 64–70. It has been altered for this republication and is translated by the author and Tim Rutherford-Johnson.

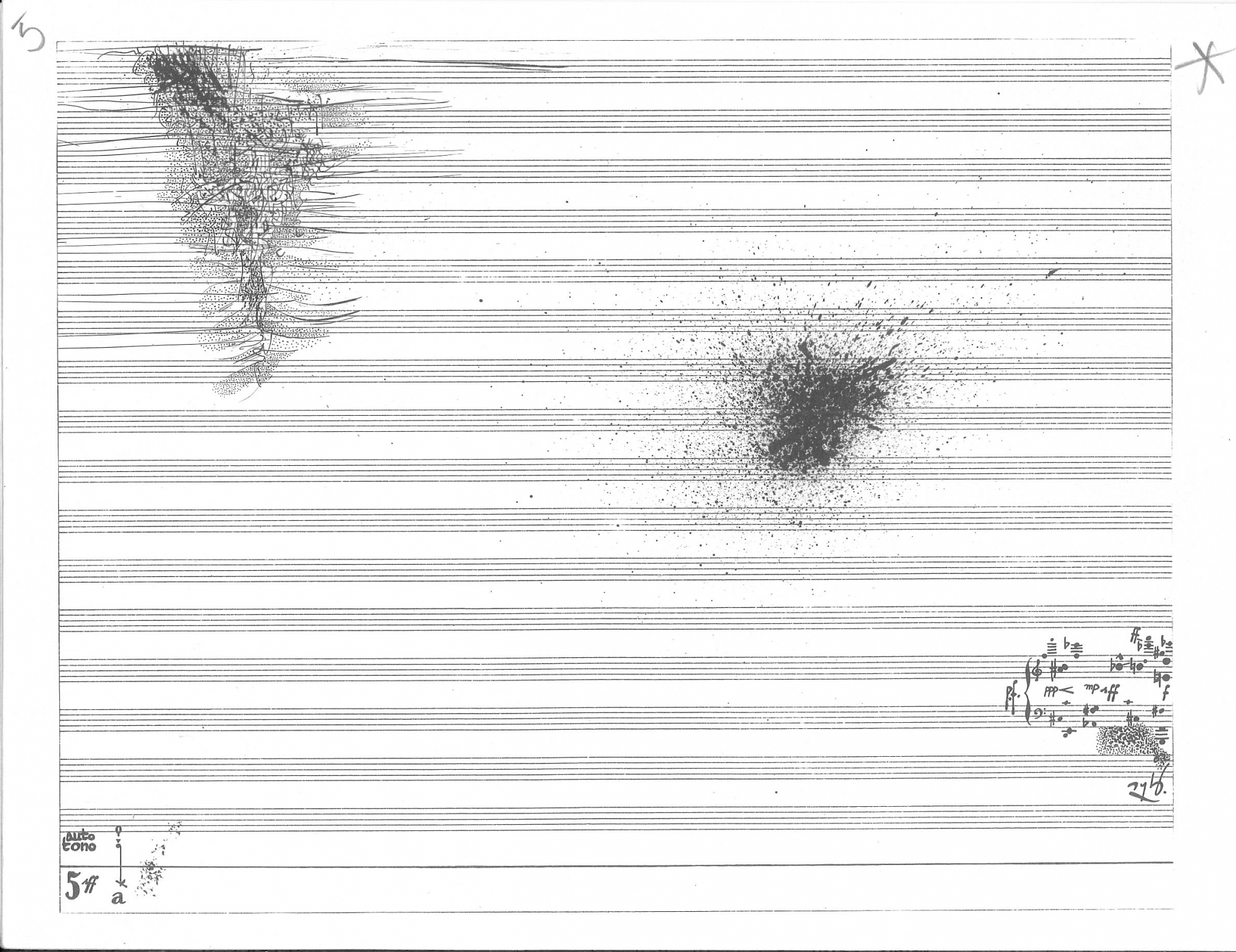

In the clamorous outburst of Beethoven’s ‘Fate Symphony’, Georg Nussbaumer hears the rooster’s ‘cock-a-doodle-doo’: another instrument for determining fate. While visiting the Beethoven House in Gneixendorf, the Viennese composer and installation and sound artist noticed that although the yard is inhabited by hundreds of roosters they do not crow at any time. When Beethoven composed his Fifth, he was already almost deaf, so he might not evenhave heard their silence. But the vain silence of the roosters could not prevent Beethoven from articulating the ‘fate’ or ‘knocking’ motive that bangs at the door in the rhythm of their crying: cock-a-doodle-doo. This is how Georg Nussbaumer’s installation Zukunftschrei(b)maschine (Future-(s)cry(ibe)-machine) presented the question at the Beethovenfest Bonn 2018. As a way to interrogate destiny and the future, the pendulum is considered another reliable measuring instrument. So it was that Nussbaumer installed a pink-painted grand piano weighing three hundred kilograms on the ceiling of the World Congress Centre in Bonn. Pulling on ropes, the audience could determine the pendulum’s movement: the faster the movement of the sounding and swinging pendulum, the more intense the knocking and crowing rhythm of the fate motif.

Real Presence

The piano is asounding and vibrating material-semiotic object,1 in which the various strands and threads of European music history meet and knot. According to Nussbaumer, it has a strange battery-like quality. Even if not all music played on the piano is heard at all times, the strings, wrapped in copper like an electric coil, are reminiscent of a storage medium, and the piano becomes the ‘battery of Central European music’. And when the grand piano swings on the silken thread on the ceiling above the heads of the audience, the referential strands of the history of this instrument resonate. Indeed, history calls the grand piano to flight: in the Baroque period, music passed first through the composer’s feather quill and then through the quill plectrums by which the strings of the harpsichord are plucked. Thus the instruments of notation as well as of sound generation, the feathers were discarded when the harpsichord became a fortepiano. But from the feathers the instrument took on the shape of a wing and from now on was also – in German at least – called a wing (‘Flügel’, referring to the instrument’s wing-like shape). Furthermore, built into the grand piano is a harp, the instrument of the weightless angels; while it also has, according to Nussbaumer,

a cow-like character: It stands like a bull on the concert podium with its stubborn stance on three legs and the double wheels that make it an even-toed ungulate. And from its snout, its teeth stare at the poor pianist. One wonders every time that someone dares to reach into the mouth of a piano. Pianists are – most of them don’t know it and perhaps also find it stupid to see it that way – animal tamers and that’s why they are well paid, of course.2

It is this ‘cowishness’ of the angelic instrument flying like a pink butterfly over the audience’s heads that Nussbaumer’s work is about. Its cow-like quality, with its floating three hundred kilos, suggests the resistance of the material against its dissolution as a conceptual reference – even if and precisely because it is not on the stage, but fluttering above our heads. The difference between materialism and conceptualism can be exemplified, with Donna Haraway, by the Protestant and Catholic interpretation of the eucharistic bread in Christianity: while to the Protestant church the host is a symbol of the body of Christ, to Catholics, according to the dogma of the ‘Real Presence’, it is in fact the true body of Christ. Haraway, the theorist of material-semiotic excess with her ‘soul indelibly marked by a Catholic formation’, highlights the ‘doctrine of the Real Presence’ when in ‘bread and wine’ she hears ‘the transubstantiated signs of the flesh’. It is a ‘corporeal join of the material and the semiotic in ways unacceptable to the secular Protestant sensibilities of the American academy and to most versions of the human science of semiotics’.3 Haraway thus pushes at the critical point of semiology: the materiality of the sign. While the rationale of sign theory depends on the detachment and exclusion of the material properties of the sign in favour of its referential and differential properties,4 the inert and sticky materiality can never be completely shaken off the sign. Whether lettering, engraving, spoken word, symbolic wine or pendulous grand piano, signs always have a concrete materiality on which their referential properties depend. On the other hand, all bodies relate to other bodies and thus have a referential character. All signs are bodies and all bodies are referential. This is Haraway’s ‘rule of truth … for those of us – practicing and lapsed Catholics and their fellow travellers – who believe that the sign and the flesh are one’.5 Haraway calls these material-semiotic unities ‘material-semiotic nodes or knots, in which diverse bodies and meanings coshape one another’.6

With the vibrating and swinging grand piano, not only do references from the entire history of music resonate, but so too do three hundred kilos of wood, copper and ivory. When Nussbaumer speaks of the ‘battery-like quality’ of the grand piano, he speaks of both the materiality of the instrument and the historical referentiality inherent in this material: ‘there has been running so much blood and sweat – at least of elephants – until someone here with us canplay a stupid sonatina’.7 The wood is mostly tropical wood, the ivory keys come from elephants and the metals are mostly mined in Africa – the continent whose shape the grand piano resembles from above. The pianist sits in Europe, touching it only with his fingertips on the northern edge, from where the inflatable boats now come.8 As an object, the piano is not only a symbol that refers to the history of music, but it is precisely what is at stake artistically, swinging, knockingand crowing above us. Nussbaumer’s work is not about revealing hidden meanings or declaring a sentiment regarding Western music’s participation and complicity in exploitation, imperialism and the killing of elephants. It would suit him rather to put a living elephant on stage and see what happens than to bother art with any of his opinions.

Media, Material and Mixed Martial Arts

Georg Nussbaumer has had to endure many attributions: composer, fine artist, installation artist, Gesamtkünstler, concept artist, multimedia artist, actionist or Fluxist. Under the previous attributions, two of these must be considered inappropriate: on the one hand Nussbaumer’s art is not conceptual in so far as conceptual art is bound to so-called ‘content aesthetics’ that ignore the specific materiality of the signifier; and on the other hand his art is not multimedia art in so far as multimedia art locates itself not in its material but in its medium.9

The difference is between the music being located within a medium as its natural and self-evident habitat, and the music encountering, challenging and responding to the demands of material. The miracle of the work of art consists precisely in maintaining the tension between material conditions and spiritual significance that is produced by artistic labour through composition – and traditionally is called its ‘form’. It is this tension that is liquidated in the concept of the medium, because instead of questioning its own precondition, in a medium, music takes its own precondition for granted. If the medium is taken as self-evident it is not itself the object of investigation and critique. The miraculous tension between material and its musical formation of its demands has been described by the recently deceased music philosopher Michel Serres through the figure of the incarnation, also taken from Catholicism (Catholicism apparently has impressed late or belated postmodernists once again searching for truth): ‘What is the incarnation? The mixing of the hard with the soft. At the birth of the Word, this soft and hard mix and even become one and the same.’10 For Serres, the mystery consists in the connection of the ‘hard’ with the ‘soft’, in the transformation of a (hard) material into (soft) music without one dissolving into the other but instead the product sustaining the character of and thus tension between both. This does not mean that music is transferred into a medium, but that it emerges from a material:

The music sounds from the instruments: lyre, viola da gamba, electric guitar; from the voices: male bass or sublime female voices; vibrating strings, oscillating columns of air: these are as hard waves as the things of the world. Emerging from this, however, the music is not reduced to it. For the acoustic sound to become music, other elements are necessary, difficult to define, but belonging to the order of the soft, namely signs preceding the sense, which make up the moving mystery of the fugue, the rap or the coloratura. … Yes, music effects an alloy between hard and soft.11

Paraphrasing Serres, the miracle is the dialectical tension of musical organization being subjected/subordinated to a material that conversely by its response to that subjection itself produces and forms the and transcends the material.12 As such, music is never identical with its precondition but is the execution of its critique through negative (trans)formative labour on it. Working within a medium doesn’t change the medium as such but executes a quantum within its given possibilities. Working on material transforms the material itself as only the artistic work on the material brings about what the material is by interpreting it.

In his elaboration of the ‘partisan concept’ of a ‘philosophy of music from aesthetic reason’, Gunnar Hindrichs draws on Hanns Eisler’s concepts of ‘stupidity in music’ and music’s ‘limited foundation’ (bornierte Grundlage13). The stupidity in music as well as its limited foundation consist in the fact that music receives its own conditions from outside, and they are not themselves its object – that is, its material. Therefore, music’s location is an enclosed paddling pool within which it can run riot, but whose narrow boundaries also constitute the limited horizon and thus limited foundation of music. ‘[Media] are – however liquefied they may present themselves – contexts of immanence.’14 The stupidity in music and its limited foundation thus consists in music’s inabilityto transcend the context of immanence that conditions it and in which it is situated. By dissolving in the medium as a paddling pool, music liquidates the vital problem of music itself. Even though Serres does not put his effort into formulating this difference, his concept of the ‘alloy between hard and soft’ is the opposite: here the problem is first posed as an alloy of the material, thus the task is only set by and at the same time, in its shaping, transformed on the material. The stupidity in the music therefore consists in a lack of self-consciousness of music by ignorance and suppression of its own objective condition. Objectivity is not neutral but carries the character of objection: the material as music’s opposite constitutes an opposition that is the negative foundation of music. This makes Hindrichs’ concept of ‘music philosophy out of aesthetic reason’ a ‘partisan concept’: ‘It is the partisan of all compositional attempts to assert the ‘New Advancing Beauty’ against the immanence of the existing,diversified and commodified music. It is a partisan concept.’15

In this framework, Nussbaumer’s ‘approach’ – with his brutal materiality– is that of a cannonball jump into the pool of media as the ‘immanence of the existing, diversified and commodified music’. Nussbaumer is not a multimedia artist, he is a mixed martial artist in full-contact combat – as, with and against Marshall McLuhan, the medium is only a message if it is at the same time itself the massage.

Among the aforementioned attributions, that of Nussbaumer as a ‘total artist’ (Gesamtkünstler) at any rate fits his work better than that of the conceptual or multimedia artist, insofar as he (like Richard Wagner) does not naturalize existing divisions of the sensible, especially not between music, text and stage design, but challenges them as objects of transformation. For him it is a ‘self-evident claim that if I am in a world that invades me through multiple senses, then I am also allowed to address it through multiple sensory channels. It would be boring for me to have to translate all this into sound, just because there is this branch of sounding music … which after all has passed its own history.’16 So, if music is indeed liquidated in the medium and thus is, as has been proclaimed many times, considered dead, this liquidation itself might be considered its state; and consequently the death of music is the state that is to be brought to experience. This requires a new artistic sensitivity for and work on the demands of and the ways of addressing the world musically, in order to be able to respond to them – in order to hear, if not the knocking of the world spirit at the door, then at least the crowing of a mute fate out of the history and the present. This reflection is an attempt to critically engage music philosophy as a partisan concept after the liquidation and death of music to grasp the possibility of its afterlife.

Liquefaction and Liquidation

Media liquefy. Serres speaks of ‘mixtures’ and the ‘alloy between hard and soft.’ Just as Nussbaumer takes his materials (a little too) seriously, we must take the terms seriously. There are literal melting processes in Nussbaumer’s work, such as in his concert installation Eine Winterreise (A Winter Journey, 2016), in which an iceberg melted on a grand piano in the Vienna Konzerthaus over a period of two weeks. The impetus for this was a project of the Vienna Association for Aesthetics and Applied Cultural Theory: ‘.akut’, which is run by the pianist Han-Gyeol Lie and the philosopher Gabriele Geml. In 2016, their event series ‘The Year Without Summer’ focused on the year 1816. Due to a volcanic eruption in Indonesia in the previous year 1815, summer never came to Europe in the following year, resulting in strange weather effects. In addition to the unusual cold, there were also mock suns, which appear in Schubert’s Winterreise – Wilhelm Müller wrote the poems that Schubert set in 1816. Nussbaumer deals with these references in his own way: he places a grand piano in the foyer of the Vienna Konzerthaus and dumps three tons of ice on it. Once again, Nussbaumer’s referential brutality has nothing of the referential lightness of conceptual representation. Not only are the works overloaded symbolically, but the symbols themselves have considerable weight: in the case of the flying piano, three hundred kilos; in the case of the iceberg, three tons.

This is not simply a conceptual joke. (Although it is that, too.) The joke paves the way for sonic subtleties. For the iceberg is also musically – to speak with Julia Kristeva – an engraving form of preparation of the piano,17 which changes through the melting process, during the two weeks in which the installation is continuously played by pianists playing accompanying figures from Schubert’s Winterreise. Under the melting ice, piano strings liberate themselves vibrantly and the instrument warps in the moisture. Nussbaumer’s ruffian gesture elicits the most subtle timbral differences from the piano. Some chords sound like hollow tapping heard from a distance, while others pass through all the transitional stages to a full – albeit out-of-tune – tone, until suddenly Schubertian motif fragments leak through the ice, so that romanticism seeps through in the most touching image. The brutalist joke thus becomes a material-semiotic knot. It’s not about ‘a representation of anything’, says Nussbaumer, ‘but what interestsme is the real’. In this way, the references to the real materialize, incorporating the various semiotic threads. Nussbaumer’s works are thus both symbolically and literally charged and loaded – as batteries and pianos – which are in both respects excessively overloaded. The iceberg materializes that which separates us cold hearted children of the present from the emotional outpourings of Romanticism. Indeed, there is something grotesque when today’s audiences melt without reservation at Schubert’s Winterreise. Nussbaumer stages the ice literally melting for us in a very real way, and so his brutality paves the way to a tender new hearing of Schubert’s figurations. Like Schubert, Nussbaumer does not know austerity and hits the keys with the same stubborn vainness. In order to reach for and repeat the Romantic gesture, the iceberg that stands as an obstacle between today and Romanticism must be put up materially and worked through. Thus, three tons of ice must be mobilized to demobilize the piano and remobilize our sensibility for what music has been or might become.

In this respect, Nussbaumer’s Winterreise forms a Janus-faced answer to Susan Buck-Morss’s Janus-faced formulation of the ‘liquidation of art as we have known it’, which warns of the loss of aesthetic experience and its critical moment in the liquidation of art, by at the same time also asking whether this loss might have already occurred and what might take its place: ‘Aesthetic experience (sensory experience) is not reducible to information. Is it old-fashioned to say so? Perhaps the era of images that are more than information is already behind us.’18 Nussbaumer’s iceberg takes both statements into account by capturing both Janus-faces – one looking to the past, one toward the future possibilities. Yes, the time of ‘art as we have known it’ is over; it has been liquidated. We can no more melt away to Schubert than we can hear Beethoven’s call to fate in the spirit of the French Revolution.19 But Nussbaumer sets against the liquidation of aesthetic experience the melting iceberg, or rather pours it out on the piano – as Schubert did, and as today only disoriented people do with their feelings. An iceberg that not only represents our icily hardened reification and our inability to melt, but it also melts for us in real terms. Through this bulkiness, however, it creates thesensitivity for a new listening to new and old sounds.

In the ‘alloys’ that are created from existing materials, we cannot simply return to the original material but must turn to something new. Serres and Nussbaumer describe such melanges similarly, though each in their own way. ‘An alloy’, Serres puts it, ‘shows and hides how one metal loses itself in another, the precious gold, for example, in the vulgar brass of small change. Take the piece in your hand and you have the gold, and you don’t; you work on the contradiction.’20 Working on contradiction means first of all sustaining the consciousness of that contradiction, which Buck-Morss articulates as the task for artists ‘to sustain the critical moment of aesthetic experience’.21 Nussbaumer describes the same as Serres in his now well known witty proverb22 of the Palatschinke (Austrian for pancake):

If I cut the pancake into pieces, I will never get to the egg again. But I will get to something else. So I can get something else out of it that is neither the original material, but is something between the pancake that is lying there rolled up with jam and the egg that was there before. In between lies a whole world of heat and reactions and colors.23

Thus it is not, and never can be, a matter of repeating history, but rather Nussbaumer lets the material of the past, as he says, ‘run through the gold-panning sieve again. If I now disassemble Wagner, I am already not disassembling a raw material, but a formed conglomerate or an amalgam, and then perhaps I am interested in something that was only a filler or binder for him, and can make something out of it again that I consider relevant for today. But of course never forgetting that none of this would work if it didn’t have that backdrop and that stage depth.’24

‘History does not repeat, but it rhymes’25

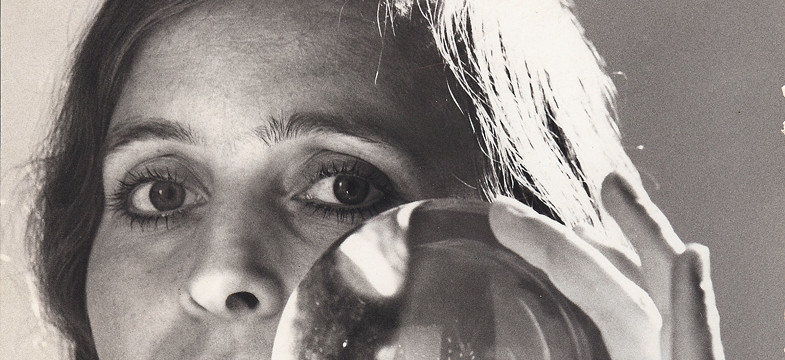

The specific form in which Nussbaumer makes history an object of critique and transformation is neither by continuing it nor by rejecting, but through a simple but witty operation: he takes the past at its literal word. In his piece Schönes Bildnis mit Mozarterwärmung (Beautiful Portrait with Mozart Warming, 2006), Tamino in Mozart’s The Magic Flute, melting in front of Pamina’s portrait, becomes a Mozartkugel melting in the mouth of the soprano Sarah Maria Sun. She places in her mouth the spherical Mozart for the twenty minutes that she sings Nussbaumer’s composition based on Tamino’s aria. During the piece, the singer is not allowed to swallow, so the chocolate Mozart drips onto her chest while she sings, ruining her beautiful dress. There are also passages from Mozart’s letters that go into the singing where the terms or concepts of ‘shit’ and ‘chocolate’ occur, but they are hard to understand; the Mozartkugel, bestseller of the commodification of the Salzburg composer, stands in the way of understanding Mozart. Once again it is obstructive and is precisely so by being a literal quotation. It is not deconstruction and deformation that characterize Nussbaumer’s work with tradition but, on the contrary, a very pedantic, exaggerated, rampant and material literalness of reference. In the question of the liquefaction of media it is also a more-than-metaphor of the possibility of a liquefied material that is not identical with its liquidation, but at the same time its realization. Thus, it becomes a material realization of the liquidation of material – which must be considered the opposite of its medialization.

For example, when he takes the common reception motifs of immersion, submergence and melting away to Wagner’s music –one of his favourite points of reference – too literally in its materialrealization.

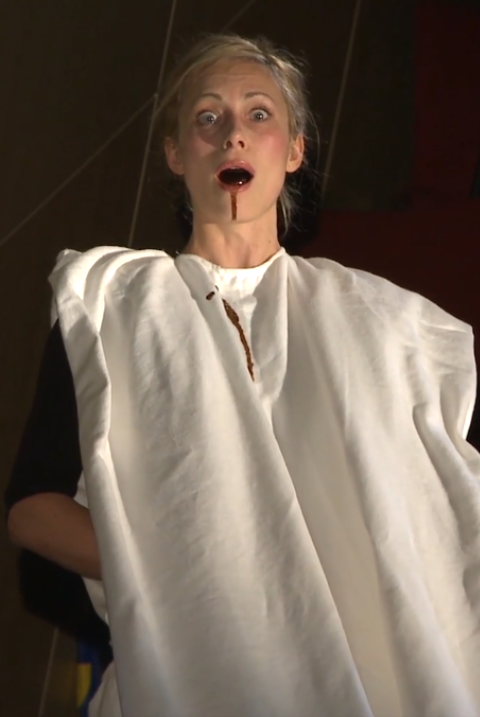

In Tristan und Apnoe (2015), the soprano – also Sarah Maria Sun in the premiere – sings the ‘Liebestod’(Love Death) from Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde extremely slowed down in the presence of an apnoea diver who seems close to drowning as a sinking Tristan. The audience watches and listens as the diver extremely slows down his pulse to hold his breath for seemingly endless durations underwater. It is uncomfortable – as if he’s suffocating. In the swimming pool opera Tristan – Schwimmen und Schweigen (Swimming and Silence, 2006), for a bathing audience, mezzo-soprano, instruments, synchronized swimmers, video and installations, the audience can not only experience the European synchronized swimming champions, the Synchron-Nixen-Mannheim, as Rhinemaidens, but can also themselves submerge in the water and thus into Wagner’s music, which is played underwater inside the pool. Nussbaumer even takes the multimedia paddling pool more seriously than this branch of the music industry takes itself.

Wagner underwater can also be experienced in the sixteen-hour installation Ringlandschaft mit Bierstrom – ein Wagner-Areal (Ringscape with Beer Stream, 2013), for ten strings, audience and beer – but without swimwear. The ‘original’ Wagner can be heard in rain barrels, but only at the price of wet hair, according to Nussbaumer, who was pleased when ‘especially dear elderly ladies stuck their heads in the water and came out again like baptized poodles but having heard Siegfried in there for a few seconds’.26 Meanwhile above the water surface, the scenic installation follows a selective score, but one that strictly follows the entire Ring, according to which, for example, whenever Wagner mentions ‘cloud’,‘fog’, or ‘haze’, fog is emitted; or whenever ‘blood’ occurs a screen is shot over seven meters by a ketchup cannon. Thus, the patterns of rhythms that emerge from Nussbaumer’s reading of a pedantic literalism would consist roughly of two hours of pause, then three ketchup bottles, then three hours of pause again. And although the first thing we might think of when we think of Wagner is rising plumes of fog, we can note here that there are two whole fogless operas in the Ring: Wagner doesn’t prescribe the fog we wish for. Instead of being true to the work, we seem to desire and beg for mystification.

Also, Wagnerian drunken ecstasy and intoxication is infused: Nussbaumer might take it out of the music but serves it back to the audience directly in liquefied form of beer. The state that arises during sixteen hours of Ringscape – premiered in the Fürstenberg brewery in Donaueschingen – is probably close to that of today’s Wagnerians in the Bayreuth swamp haze. ‘What runs through Germany? The Rhine and the beer. Period. Will do!’27 Once again Nussbaumer is too rigorous in his faithfulness to the original. These operations squeeze something new out of tradition, not by rejecting it but, on the contrary, by taking it too seriously:

So, if there is a technique, it is not to change a regulated system, but to enter it with acertain naiveté. For example, there are these doors supermarkets where you going by the bar, then you shop, and then you leave behind the checkout. If you enter the system from the wrong direction, it will beep. I take it as it is, but enter it from another entrance and automatically something happens.28

Through these approaches of the tradition on paths that are not ratified by the dominant interpretations, Nussbaumer provokes effects of history left aside without offering a new ‘dominant’ interpretation – it has all been there already. There is a way in which this responds to Benjamin’s attempt to redeem history, formulated in the third of his ‘Theses on the concept of history’ of 1940:

The chronicler who narrates events without distinguishing between major and minor ones acts in accord with the following truth: nothing that has ever happened should be regardedas lost to history. Of course only a redeemed mankind is granted the fullnessof its past – which is to say, only for a redeemed mankind has its past become citable in all its moments. Each moment it has lived becomes a citation à l’ordre du jour. And that day is Judgment Day.29

Although neither the aim of Judgment Day nor the end goal in the idea of a redeemed mankind are graspable for us as they still might have been for Benjamin, it is the means, the instrument of making the past citable, that Nussbaumer’s work shares with Benjamin’s Marxist project of redemption. In the absence of forms by which to experience history – also diagnosed by Benjamin30– it is of course not at all clear to which end that citation is a means. But more than affirming any goal of history, Nussbaumer’s art is that of working through its past.

The Jacobin Hairdresser of Music History

Thus, Nussbaumer’s assertion that music has ‘passed its own history’ does not lead him to reject what history tasked us with and drown and liquidate it in the paddling pool, but rather to sensitize us in the present to the simultaneous presence and absence of history. This does not allow us to unbrokenly and without shame pick up its thread and continue to drift in the flow of historical so-called progress. In order to gain access to the lost history, Nussbaumer interrupts its stream by streamlining it against itself. His art sets up history as aproblem by materializing it and placing it in our path as a bulky object that is at once product of, objective and obstacle to itself. It is an attempt to brush history against the grain, as Benjamin put it in his ‘Theses on the Concept of History’, the seventh of which might enlighten the question of historical materialism in the age of the death of the material:

Whoever has emerged victorious participates to this day in the triumphal procession in which the present rulers step over those who are lying prostrate. According to traditional practice, the spoils are carried along in the procession. They are called cultural treasures, and a historical materialist views them with cautious detachment. For without exception the cultural treasures he surveys have an origin which he cannot contemplate without horror. They owe their existence not only to the efforts of the great minds and talents who have created them, but also to the anonymous toil of their contemporaries. There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism. And just as such a document is not free of barbarism, barbarism taints also the manner in which it was transmitted from one owner to another. A historical materialist therefore dissociates himself from it as far as possible. He regards it as his task to brush history against the grain.31

The sectional domestication of art in the media is therefore not only a symptom of its ‘limited foundation’ and of ‘stupidity in music’, but is also playful subordination under the dominant tradition, the tradition of dominance. For Nussbaumer, the phrase of the ‘brushing against the grain’ of history makes him

think of the hairdresser’s profession, because the kind of composing, which uncritically submits to and runs on the ticket of the rail track of historical progress, is basically like trying to simply snip different hairstyles on the same head over and over again. And you can do that, but it will never be anything other than a hairstyle. This head will never become another person who could be able to say something reasonable and new. That’s why I would say that sometimes it’s okay to change the head.32

Nussbaumer, who himself wears a shaven head, also sees the attraction of cutting an orchestra’s hairstyle. But maybe sometimes it is necessary to do more: to scare music history by cutting its head off with the guillotine and holding it in front of itself.

Notes

[1] See Donna Haraway, When Species Meet (Minneapolis, 2008).

[2] Georg Nussbaumer in conversation with the author, 3 September 2019.

[3] Donna Haraway, The Companion Species Manifesto (Chicago, 2003), pp. 15–16.

[4] Ferdinand de Saussure, Cours de linguistique générale (Paris, 1971 [1916]), pp. 97ff.

[5] Haraway 2003, p. 17.

[6] Haraway 2008, p. 4.

[7] Georg Nussbaumer in conversationwith the author, 5 September 2018, published as: ‘Feige Kunst ist unerträglich’, in Bernhard Günther, Jim Igor Kallenberg (eds.), Wien Modern 31: Sicherheit, Festival programme (Vienna, 2018), p. 165.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Gunnar Hindrichs, ‘Musikphilosophie aus ästhetischer Vernunft’ (Philosophy of Music through Aesthetic Reason), in Wolfgang Fuhrmann, Claus-Steffen Mahnkopf (eds.), Perspektiven der Musikphilosophie (Frankfurt 2021), pp. 43–58. Translation by the author and Christoph Haffter.

[10] Michel Serres, Musik (Berlin,2015), p. 152. Translation by the author.

[11] Ibid., 157–8.

[12] See Gunnar Hindrichs, DieAutonomie des Klangs (Frankfurt, 2014), pp. 55–6. Translation by the author.

[13] As a translation of the term ‘Borniertheit’ used by Eisler, I have chosen not the usual translation of ‘narrow-mindedness’, because this would reduce the problem to a mental limitation. In fact, in the Marxist tradition that is shared by both Eisler and Hindrichs, the term has a specific character, articulating the social, political, spiritual and economic condition of human freedom within capitalism. In Marx’s Grundrisse (1857–61) the social and individual freedom are restricted by the ‘limited foundation’ (bornierte Grundlage) they have to serve in capitalism. The dynamic of freedom thus pushes to the overcoming of this limited foundation: ‘Forces of production and social relations – two different sides of the development of the social individual – appear to capital as mere means, and are merely means for it to produce on its limited foundation. In fact, however, they are the material conditions to blow this foundation sky-high.’ (Karl Marx, The Grundrisse, in The Marx-Engels Reader [New York, 1978], pp. 221–93: 285. Available at: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1857/grundrisse/ch14.htm).

[14] Hindrichs, ‘Philosophy of Music through Aesthetic Reason’.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Nussbaumer in Kallenberg 2018, p. 165.

[17] Julia Kristeva, Die Revolution der poetischen Sprache (Frankfurt, 1978). For Kristeva, the engraving is an essential function of material semiotics and explicates its origin in the work on significant materials by indicating the translation of the Greek term δημειον (sémeion): ‘distinctive feature, trace, characteristic, prognostic symptoms, proof, engraved or writ sign, imprint, hint, design’; ibid., 35. On the corporeity of compositional work, see also Ferdinand Zehentreiter, Musikästhetik(Hofheim, 2017).

[18] Susan Buck-Morss, ‘Answer to the Visual Culture Questionnaire’, October, Summer 1996, p. 30.

[19] See Leo Samama, The Meaning ofMusic (Amsterdam University Press, 2016), p. 115: ‘The entire symphony is all about war and freedom, and more generally about the positive promises that inspirited citizens in big cities after 1789. Everything would finally improve: long live the free man!’

[20] Serres, Musik, p. 156.

[21] Buck-Morss continues: ‘Our work ascritics is to recognise it.’ Buck-Morss, ‘Answer to the Visual CultureQuestionnaire’, p. 29. The liquidation of the critical moment of aesthetic experience thus expresses not just a regression of art production but also a regression of art criticism. If Georg Nussbaumer were to make the fate crow and we didn’t recognize it, it would be a failure of critique.

[22] See Lydia Goehr, Red Sea – Red Square – Red Thread (Oxford, 2022).

[23] Georg Nussbaumer in conversation with the author, 5 September 2018.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Fahim Amir, lecture series given 2015/16 at Kunstuniversität Linz (‘Geschichte wiederholt sich nicht, aber sie reimt sich’), approached temporality and historicity after their alleged end not as a ‘container filled with facts’ but as a ‘space of authoritarian and dissident praxis.’ Translation by the author.

[26] Nussbaumer in conversation with the author, 3 September 2019.

[27] Nussbaumer in conversation with the author, 3 September 2019.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Walter Benjamin, ‘Theses on the Concept of History’, Selected Writings, vol. 4 (Harvard 2003 [1940]), p.390.

[30] Walter Benjamin, ‘Experience and Poverty’, Selected Writings, vol. 2/2 (Harvard, 2005 [1933]), pp. 731–6.

[31] Benjamin, ‘Theses on the Concept of History’, pp. 391–2.

[32] Nussbaumer in conversation with the author, 3 September 2019.