At Darmstadt’s Summer Courses, New Music Transitions in Real Time

by Assaf Shelleg

The Darmstadt summer courses, one of the storied and contentious hubs of contemporary music since 1946, is transitioning in high decibels while rebranding itself silently.

Amid Germany’s sweltering summer heat, young composers and musicians rush from classes to workshops, from concerts of very recent works to lectures on machine subjectivity, the non-binary future of music, and 3D sonic objects. Add to that the off-the-grid yet monitored “open space” venue, where meetings offer everything from improvised concerts to “psychoanalysis for musicians,” and you will get a sense of what music and contemporaneity could mean.

Thomas Schäfer, artistic director since 2009, assured me that modernist staples like works by Karlheinz Stockhausen, Brian Ferneyhough, and Brice Pauset will endure. Yet Schäfer’s curation hints at a bolder shift evident throughout the different concerts: a non-hierarchical space wherein score-based composers, sound artists, electronic music composers, DJs, and improvisers become equal members of the republic of Darmstadt—and by metonymy of the contemporary music to come.

The maze that is Darmstadt is impossible to exhaust with events overlapping relentlessly, but during my week there I could sample some of the captivating transitions that were signaled already in the 2023 edition, as chronicled by Seth Colter Walls.

These transitions spotlight George Aperghis and Clara Iannotta, lesser-known outside the narrow niche of new music circles but priest-like figures for global students grappling with modernism’s rapid obsolescence—including artists in their early forties like Iannotta.

Florentin Ginot perfoming in Darmstadt © Kristof Lemp / IMD

That pace was on display in the first week of the courses, and particularly at the Sunday morning concert on July 20. Double bassist Florentin Ginot, a faculty tutor, performed three solo works: Aperghis’ 2018 Obstinate, Iannotta’s 2023-25 a blur of fur and bone (ii), and an improvisation for double bass with pedals. Together, these works underscored the erosion of hierarchies between formal and spontaneous composition while highlighting the presence of hybrid practices and digital mediations.

Aperghis’ Obstinate evokes a transcription, spawning numerous variants of a melodic contour whose prototype remains absent. By variants, I mean those subspecies whose degree of difference is insufficient to merit a distinctive subtype; now add dozens of such indistinct variants, and they defy notions of a source or a theme. Or causality.

Aperghis, in other words, acts like an ethnographer transcribing oral musical traditions, with abundant look-alike formations that are almost indistinguishable from one another. Concatenated, these variants generate cascading imagery that flow incessantly—hence the work’s title, Obstinate. Yet Aperghis doesn’t stop there; he projects some of these developments onto the performer, assigning notated vocalities and syllables to generate more variants—some of which transform into language. The double bassist and his instrument gradually project their mutuality and render melodic origins null.

Iannotta’s a blur of fur and bone (ii) nods to her mentor Chaya Czernowin (a Darmstadt fixture since the 1990s) with its violently surreal title, but diverges by opting for electronic manipulations at the expense of form. The double bass is augmented into a bigger, hybrid whole, with each demanding gesture processed and ventriloquized electronically to produce an aura that occasionally ensnares the composer in passivity. The blur, then, is that of old craftsmanship heading toward immersive sounds, straddling the ground between notation and unscriptable actions. This is where decisions rely on the performer almost as much as the composer.

Almost. Which is why Ginot’s improvisation clinched his composer status. Switching to an amplified double bass with a set of pedals usually associated with electric guitarists, the virtuosic encore paired stunning technique with technology, reenacting the instrument as an electric guitar mutant and asserting the new status of unwritten music.

In retrospect, Ginot’s concert echoed the opening concert of July 19: Peter Ablinger’s WEISS/WEISSLICH 20 was a performance piece featuring dense cymbal rolls that preceded the audience entrance and ended abruptly long after we sat down; Inti Figgis-Vizueta’s to give you form and breadth for three percussionists simulated oral knowledge transfer through changing patterns and variants on domestic objects; and Alexander Babel’s Snare Counterpoint for four percussionists complemented the latter work, except that its repetitive motifs unfolded through discontinuities. All works were multifunctional. As such they conveyed accessibility, performability, euphony, multipurposeness, and immersive sounds, even if built from percussive pixels—and they emerged as a critique of the still dominant hierarchies in late-modern and contemporary music.

The 4tet Laboratoire concert—an ensemble of two synthesizers and two percussionists—showcased works by two young composers in their thirties for whom the endless proliferation of musical images, genres, and ecologies of sound necessitated neither order nor commitment. Simon Bahr’s The Mock-up Pop-up Medley featured ceaseless montaging of various musical leftovers—attention-garnering snippets like music for TV ads from the ‘70s, sampling soundbites from the ‘90s; kitschy music, yet without derogation; or impressive but foreseeable syncs à la Bang on a Can.

Everything kept on changing nervously and equally indifferently, like a glitchy AI playlist—uncaring if materials were citations, paraphrases, allusions, pastiches, augmentations, or fragments. There was no difference between them as far as Bahr was concerned. All were embraced with enthusiasm—and a shrug.

Impact peaked with Aya Metwalli’s Salute to the Groom, which opened with a field recording of an Arab wedding song. Metwalli drew unsystematically from this import, deconstructing its rhythms and melodies and reassembling them in an incomplete manner with some asymmetrical additives. In the process, she disregarded occasional affirmations of Arab musical stereotypes, and put together the ethnographic source very vividly, to the point of transcending clichés on cultural appropriation.

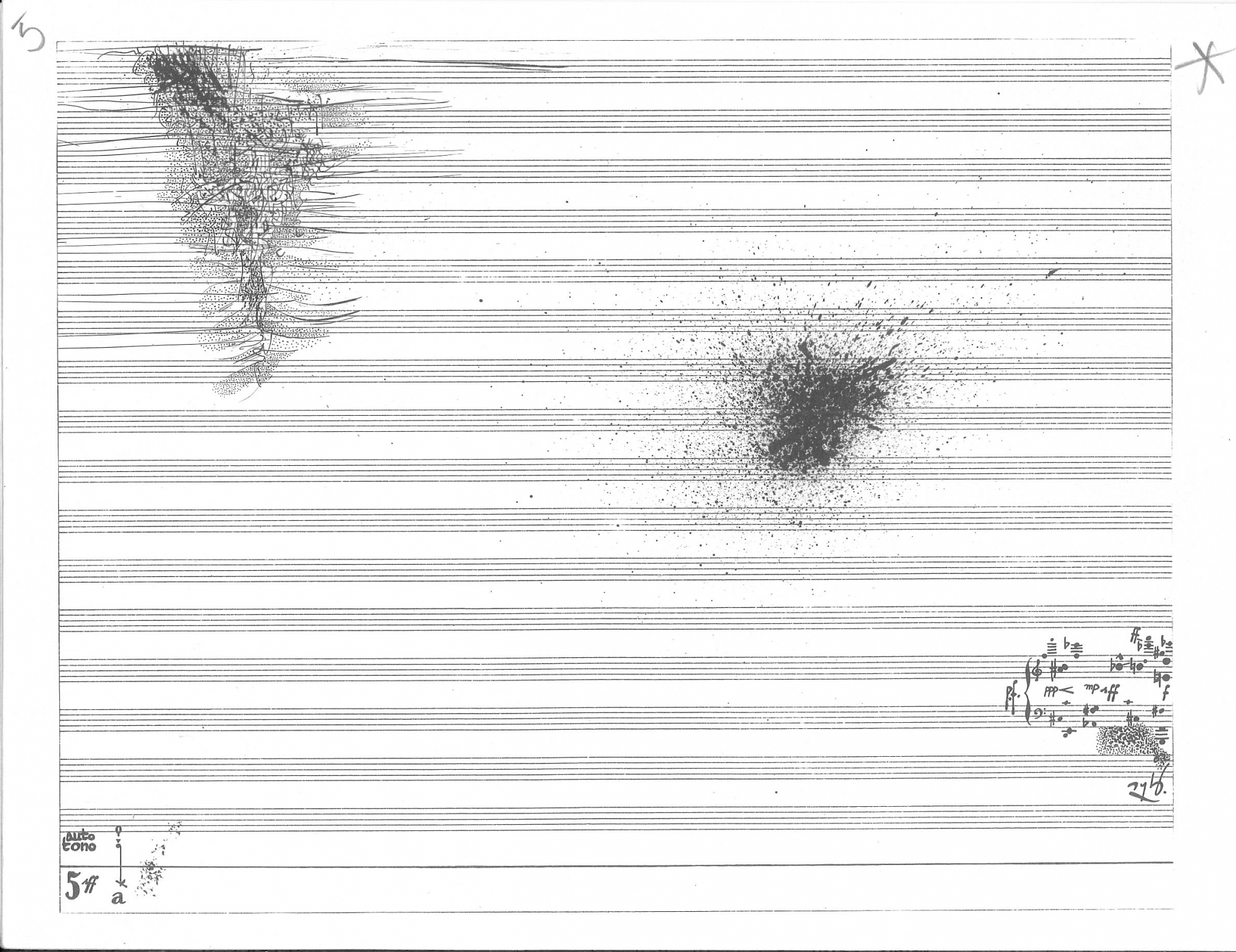

Surprise doubled when collaborative work, improvisation, relative accessibility, and oral latitudes met craftsmanship and earned near-consensus from Darmstadt’s young and old cohorts. Il Teatro Rosso, an eclectic musical film by cinematographer Huei Lin and composer Steven Kazuo Takasugi, destabilized the lines separating composition from improvisation. Working with the Montreal-based collective NO HAY BANDA, the dedicatees of the work, Takasugi cut their music into dots that were further minced into pixels. The 65-year-old Takasugi concatenated these pixels vertically and horizontally into spasmatic phrases, animating an otherwise inflexible stasis.

NO HAY BANDA performing Steven Takasugi’s Teatro Rosso in Darmstadt © Kristof Lemp / IMD

Takasugi’s composed contractions were relentlessly doubled by abundant displacements of calculated syncs and predetermined latencies with the Lin’s film, disorienting listeners in space and time through prerecorded music and the live agents. But which version is the real one? The disorientation is not just of linearity and temporality but also of truth and fiction—all while redemption is splintered by disillusionment into tiny bits of nostalgia.

Classic modernist concerts persisted, featuring pianist Nicolas Hodges and cellist Lucas Fels, who rigorously demonstrated demanding extended techniques and ineffable timbres—like the mesmerizing Two Songs Without Words for cello and piano by Wolfgang Rihm, or in Evan Johnson’s A fountain for solo piano, which spells new sonic thresholds (as he did in the 2023 edition with his dust book for solo viola d’amore). Still, despite the unrivaled mastery the Hodges-Fels duo, the concert felt somewhat museological—a minority amid the forward tilt.

Meanwhile, a talk in the non-monitored “open space” convened composers, musicologists, and musicians in a gathering promoted by word of mouth by Takasugi himself. We discussed the old Darmstadt summer courses and the lack of present-day critique, while Takasugi warned against institutionalized dissent. In what felt like a Star Wars rebel assembly we plotted change, not knowing if contemporary critique would co-opt.

Darmstadt’s momentum suggests an evolution, making the 2027 edition unmissable.

Assaf Shelleg teaches musicology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. His recent book The State of Afterness: Contemporary Music in and about Israel was published by Oxford University Press in 2025.