Partisan Critique @ 2025 Darmstadt Summer Courses

For the 2025 Darmstadt Summer Courses, Partisan Notes organized daily discussion sessions during the second festival week. We discussed our experiences of the concerts, reflected on current developments of contemporary music and exchanged ideas about the role and relevance of music criticism. This event was realized in collaboration with the Frankfurt Society for New Music (FGNM).

The following texts emerged out of the discussions: In the first essay, Christian Gregori presents and discusses three pieces from the Open Space, while in the second, Lucian Spohr critically engages with IONOS by Maia Urstad and Jean Baudrillard’s concept of hyperreality.

Three ways of avoiding simple notes

Three pieces from Basel composers – Christian Gregori

This year’s Open Space set itself apart with an energy that felt sharper and riskier than the official program, trying to challenge the official program and attract attention towards the young generation. While the institutional lectures and concerts avoided controversy, the younger composers used their platform to frame their works with ambitious, even combative, presentations.

We invited inoto our Visite Critique sessions three composers from Basel to discuss their own works with us: Dakota Wayne, Raphaël Belfiore and Carmel Curiel.

All are very different in their musical approach, but seem to articulate a shared problem for present-day composing, something that Wayne and Belfiore also spoke about in their lectures in the open space, which can be read on their new website Post-Music Post. The problem being that you cannot simply compose a note. Each composition responds differently – by pushing performance and immediacy into confrontation, by embedding the work in an elaborate conceptual framework or through painstaking manipulation of the instrument.

Dakota Wayne – „C 📹 👋🎹🌊🎼🎤H“ for piano, electronics and video

Question: What lies between the notes C and H on the piano?

- The technical answer would be: six whole-steps – or 12 half-steps.

- The hopeful answer would be: a room for self-expression.

- The pessimistic answer: a cage.

Unintended, but fitting for the piece, the pianist (Oleksandra Katsalap) did not enter the stage from the side but has been crouching behind the piano, clearly visible for everyone to see, for the last two pieces already. She finally comes out wearing a helmet – maybe also burdened by it – modified by a microphone, flashlight and smartphone, that streams her view onto a screen behind her. As soon as she sits at the piano and turns on the flashlight, waves appear behind her on the screen. Not the clean calming waves of a pretentious yoga-session, but CGI waves, that are at the same time over and underproduced – they are glossy and shiny, a bit trashy, but you can still see the piano through them, as if they are not strong enough to drown out the room. It immediately sets the expectation the following will be as tongue-in-cheek, as ironic as these waves, but at the same time they root this piece deeply in our current times, referencing social media filters.

The piece starts out with a dialogue – in a way as many great traditional pieces, so much that dialogue itself as a musical topos seems to be ‘verbraucht’ [used up], as Adorno would have said, reserved only to the ever-hopeful neo-romantics. This dialogue is in no way ‘verbraucht’, the two hands of the pianist mimicking mouths with little eyes drawn on them let out grotesque and neurotic screeches and cries – visible only through the waves on the projected screen as a dense counterpoint where the hands dash over the keys. Both hands talking with the same voice while disagreeing before slamming their faces – by which I mean the hands of the pianist – with a grand gesture into the keys. Alas, no real sound comes out, as the whole piano seems to be damped from the inside. Only the mechanical crash and its modulated reverb that seems dictated, pushed onto the tried but failed grand statement from the outside.

The crashing slowly turns into swaying, matching the projected waves, all while producing the Guerro-like, wave riding sounds of sliding up and down the keys, the pianist leaning her body all the way in until she nearly falls. But the glissandi aren’t as smooth as the waves. Sometimes the fingers get stuck, a note rings out, almost as if accidentally left undampened.

Then the pianist transcends the boundary of the highest e of the piano and turns her head further all the way until she sees the projection of herself while the video feedback is turning into an endless mirror. It is here – a point she came to by sheer accident of falling over the border of the instrument – where she realises her own situation, where the hyper-produced mediality through self-reflection turns to immediacy. Her only reaction – a naïve and helpless one, but also the only reaction until now in which poesis was possible – is to mimic a butterfly with her hands, releasing it into freedom.

From here on things grow disturbed. Determined for expression that couldn’t realise itself between the keys, she turns to pen and paper but falls into drawing a note, circling over and over and over and then all the way back over and over again until the pen breaks, which still doesn’t hinder her from trying to continue drawing. She doesn’t care for its dysfunctionality, but the note she is trying to composer is itself alone on the blank paper. This pessimism also reflects itself in the screeching sound the broken pen makes on the sheet of paper.

Frustrated she throws away the drawing only to resort to her last possible way for expression – banging her head on the keys. Hard. Loud. Without stopping. It’s just crashing sounds from here on, the camera flies towards the keys, and the resulting sound drowns out in reverb. The force, the will of these dramatic gestures is buried under waves and waves of reverb. Here, in the reverb, sound finally comes to the forefront, after being subsumed under visual theatre until now. The reverb starts to feedback and surrounds the room. It seems like a release, but the immediacy of media, that has been the token of ironic attacks until now, is mirrored here in an immersive and immediate soundscape.

It is not a surprise that the pianist’s last act is one of complete helplessness – ending the piece by falling off the piano, while behind her on the screen a glossy red note drowns in the sea.

This piece, in combination with the lecture held by Dakota Wayne the week before, tries to be a critique of a push towards immediacy by institutions. The illusion of immediacy is kept alive only by the mediation as immersion. For Wayne immersion should act as an aesthetic category next to others, not as a way out for new music problems. In his text and also in his piece, Wayne presents to us a problem of modern-day composing, “the undead quality of aesthetic value today”, all while neither deciding for “media-affirming musical contents, nor negatively as media-negating musical contents.”

This explains the tightly constructed interplay of sound and visuality in C📹👋🎹🌊🎼🎤H. But I find myself questioning one intrinsic tension of the piece. Trying to display a musical problem, the music itself seems to play little part of the composition. Whenever actions are thought musically – dialogue, grand gestures, glissandi – the visuality overwhelms any sound produced. Our eyes are drawn apart between pianist and screen, where the action takes place, but our ears are not needed to understand the piece. Music appears less as sound and more as a semantical placeholder for this construed problem, in a way making the need for music redundant. I feel there lies a true pessimism of this piece: fighting not towards music, but for the sake of fighting.

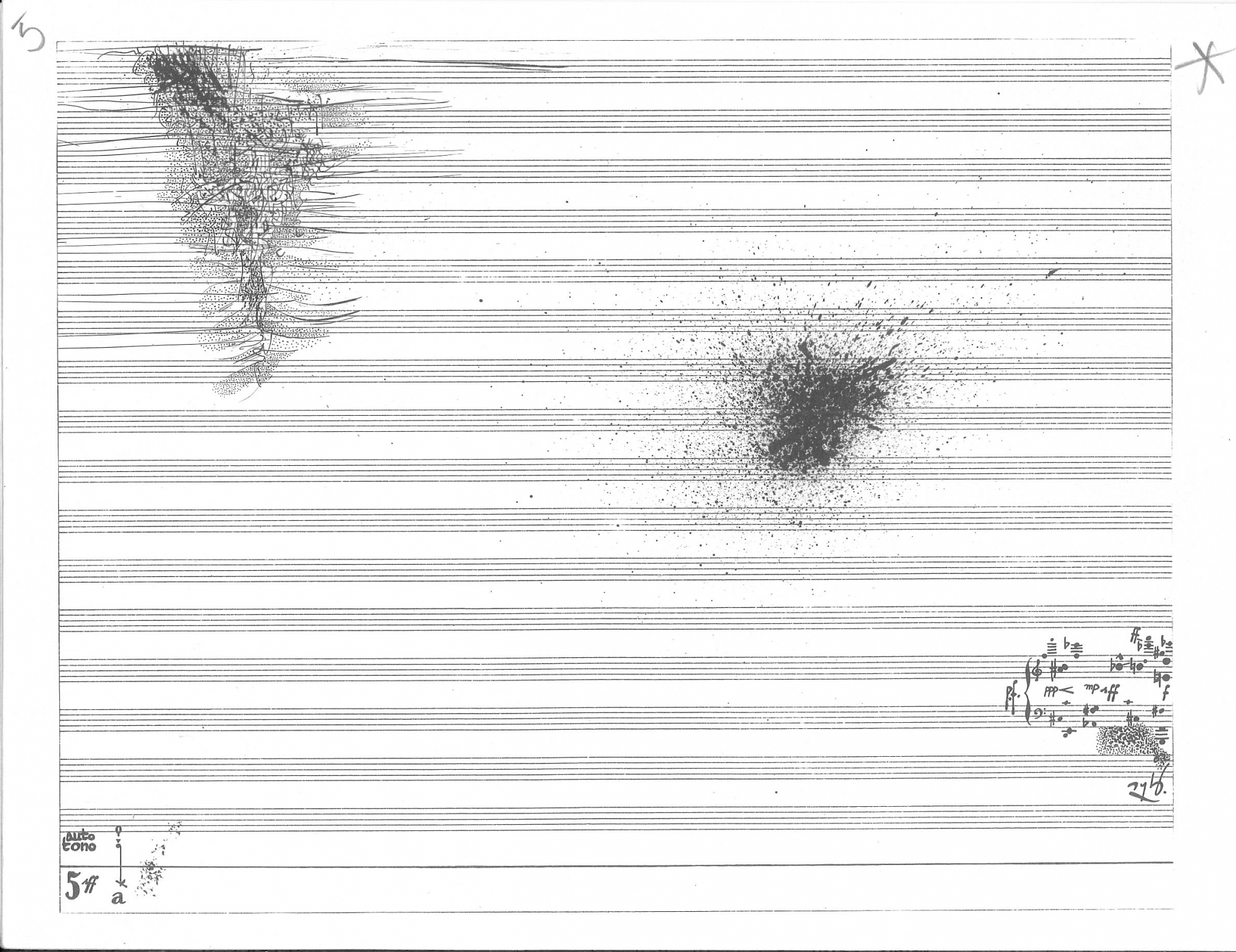

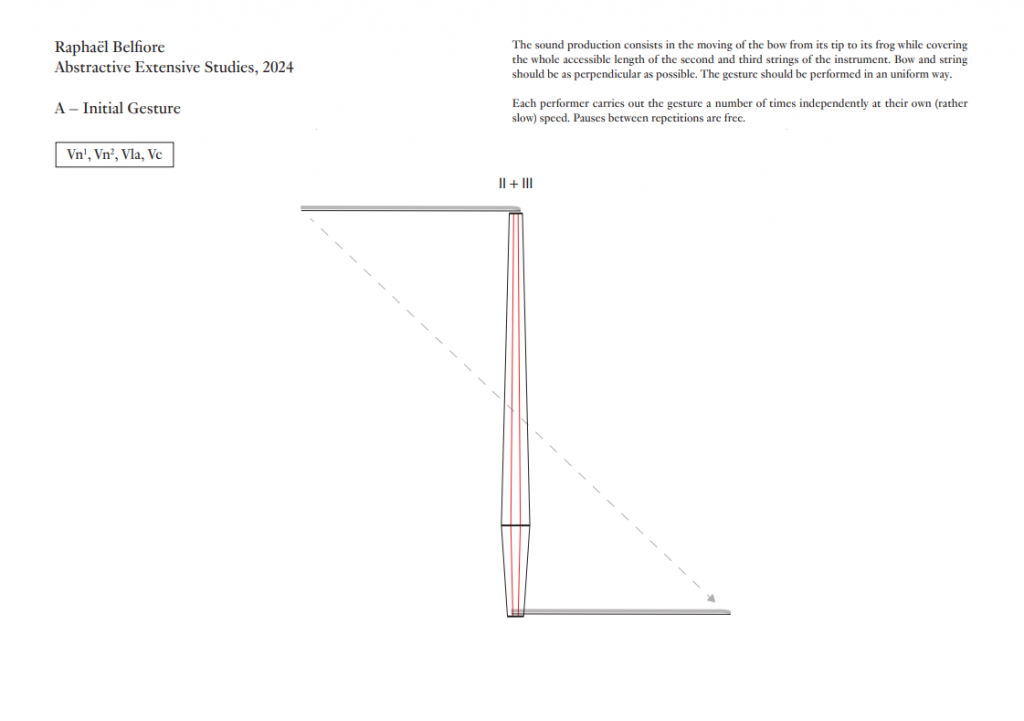

Raphaël Belfiore – „Abstractive extensive studies“ for String Quartet

What happens to music if it is abstracted to such a level that music becomes only an accidental output of a composition? To put it bluntly, this is what I believed happened in “Abstractive Extensive Studies” by Raphaël Belfiore. (You can listen to an audio of the piece here)

It is a pure body-gesture that this piece takes as a starting point. Violins and viola are placed in the lap, the left hand merely concerned with holding the instrument while the right hand pushes down the bow to the bottom left, over the bridge, towards the tailpiece. The unbothered open tuned strings produce sounds that shift with differing pressure and seem to occur by accident yet bound together by this pure gesture. Everything that happens along the way is contained in this field of possibility, a complex class of events presented by this starting gesture. This simple gesture is the basis of the whole composition, it is the Urpflanze from which the composition grows as Belfiore says “through various levels of abstraction and concreteness”.

While the first movement features synchronized downward strokes, they slowly go out of sync in the second movement before reaching an opposition in which the violins only gesture above the bridge, while viola and cello play below. From then on, the gesture grows shorter and more rigid before reaching a halt in the fourth movement where the gestures reduce to impulses, by this point so fragmented that the textural sound turns pointillistic. The field of possibility has narrowed down to only a single point – different for each instrument – reaching a dead end where it stagnates and then stops.

There is something frustrating about the experience of the piece. One feels trapped in this linear perspective. There is a dedicated logic to it, which becomes clear halfway through the piece. But as soon as the logic is figured out, one awaits a switch that never happens. This makes the piece both anxious and yet completely sober.

Although the logic of the piece seems simple, there is a complex concept behind it, drawing on the physics and metaphysics of the English mathematician-philosopher Alfred North Whitehead. In Whitehead’s theory space and time are ideal abstractions that contradict lived experience. To approximate space and time one must form classes of events that converge towards those ideal abstractions. This is where Belfiore draws the name “Abstractive extensions”.

This concept is combined with Belfiore’s distinction between horizontal and vertical musical thinking, as explained in his lecture. Whereas horizontal thinking describes musical history as a history of redefinitions and negations– the sequenced novelty for novelty’s sake of twentieth century avantgarde-music – vertical thinking tries to approach music extra-musically, by thinking through music rather than about music – which is what Belfiore attempts when he adapts Whitehead’s thinking through music. When talking about verticality, Belfiore puts the thought first: An incursion of thought in general is only secondly thought through music, concretises there in a musical work. But it is general thought that is the true innovator of music, not musical thought.

Taking this vertical thinking radically would mean a rejection of aesthetic categories that are purely musical, and that have developed horizontally in avantgarde music through the negation of the former. Because if broken down to it’s basic movement, thinking horizontally means thinking through and with musical history. To think radically vertical would mean going before horizontality, before music history, rediscovering “the experience of such a musical work [as] comparable to that of a mathematical or philosophical concretization.” Rediscovering music before its own history.

In the discussion of the piece with the composer and a member of the string quartet an interesting problem arose concerning the realisation process of such a vertically conceived concept. While comparing two different performances of this piece Belfiore was asked why he didn’t write down specific instructions such as piano, if he wanted them. A quick look at the score shows that it is as abstract as its concept, seeking to be true to its vertical approach by rejecting conventional notation. But then, if thought radically, rejecting horizontality means rejecting notions such as piano. This itself is not a problem, but then questions follow up: must one also reject the notion of a successful performance? Do we have to question the coherence of work identity? Maybe rejecting horizontality outright would cost too much.

Carmel Curiel – “For now, time is a duration of a thought” for extended piano and electronics

Carmel Curiel’s piano piece “For now, time is a duration of a thought” starts with a visual experience as well. The dimly lit grand piano is prepared with additional strings stretched between the lid and the strings, laden with wooden beads of various sizes, held in place by small wooden paper clips. Before the piece starts this is already a sight to behold. The strings, beads and clips are mirrored in the black lid over a reflection of the inside of the piano, like stars in the night sky.

Then the pianist (Raphaëlle Proust) reaches into this construction and releases a wooden bead that visibly slides down onto the g’-string and lets out a semi-muted ring, not touching the keyboard, which will remain closed for the entire piece. What will happen now becomes very clear. It is Chekhov’s gun: we expect that all those beads hanging in the strings – 149 beads in total – will come crashing down into the piano. We see the whole length of the piece laid out in those beads and with every release we see the progress towards the end.

After a few seconds of the g ringing out it is repeated before being joined by a B-flat in the lower register and a d’’ in the higher register. A faint tonality shimmers with this inverted g minor chord that is followed in the first minutes by small thirds. At other times we hear a chromatic downward motion in the bass voice acting as pedal notes for the melodies on top to feel anchored and connected. This tonality is noticeable but fleeting, as the notes are always disconnected through the action of letting go of a new bead and the occasionally removing the held paper clips in a small bucket.

These sparse melodies grow more varied until you start to mistrust some of the notes as they seem to appear out of thin air. The suspicion is correct: there is a hidden speaker under the piano which plays a prerecorded tape which consists of samples from a similarly constructed piano. At first there is no audible difference between tape and live-performance – only when you can’t correlate an action by the pianist and the sound you can recognise the tape.

Over time you notice through the reflection on the lid how the beads are slowly piling up inside the piano and this takes a toll on the strings, which are already muted by the strings attached to them. Sometimes strings become fully muted, while at other times the balls bounce off each other and a small rattling sound appears. The electronics grow more complex, trying to play in unison with the pianist and even growing to a faint waltz rhythm that the pianist can’t keep up with.

It is here that a few beads remain in the web of strings. But the pianist knows again how to mess with our expectations, catching a bead midfall. Even after none of the beads are left and they lie piled up in the piano, she manages to find a string under the piano that falls towards the pedal and a final string that leads far away from the piano to a window across the room. During these last two unexpected beads the electronics fade out in melodies that faintly recall that small waltz moment.

Time – as indicated by the title – occupies a central position in this piece. On the microlevel the piano sound is not the result of simply playing on the keys – where time is somehow hidden by the instantaneity of the mechanics – but by releasing the beads and watching them fall onto the keyboard. The only action by the pianist is the release of the paper clip while the consequences unfold before us into sound. You see the linearity of time when the bead falls – an anticipation before the sound – while the sound itself is beyond the control of the pianist.

On the macrolevel there is this situation of Chekhov’s gun, where you see the coming events before the piece has started and simultaneously you watch the beads slowly pile up inside the piano, materialising its own history. Every note played becomes a hindrance for future notes, it muddles the sound of the string for the next beads to come, the consequence being that the end of the piece is almost purely electronic, while the second-to-last bead can only fall outside of the piano. (On a different note: the composer explained that the number of beads was limited by the weight she put on the lid of the piano – any more notes and the lid might not have been able to bear the weight.) The limitations for the pianist are so great that the electronics are needed and only there it is possible for a waltz to appear.

One could burden the piece with theoretical baggage, viewing it as a story of music history where every composition slowly fills the piano with the baggage of its own past – as Johannes Kreidler does in his film 20:21 Rhythms of History when he places a CGI-piano in a hall where it has been playing for a while, and accordingly the hall is trashed with notes lying all around, choking the piano to death. There is some truth to this reading as the piece clearly deals with time and therefore history. The faint shimmering of tonality that can never fully develop, even when trying to play a waltz also places this piece into a relationship with music history. The present state of this history makes it impossible to simply play the piano with its keys – as Chopin could. One apparently needs to construct a web of strings on top of this very constructed instrument – a process which takes several hours of preparation – just to write for and play it.

But it also works as a more lightly reading, as a poetical investigation of letting go as both falling and letting something unfold without intervening.

Musical Simulation and Hyperreality

Reflection on Baudrillard and IONOS – Music in the Ether by Maia Urstad – Lucian Spohr

(german version below)

In the following reflection, I aim to elaborate on certain aspects of the concert installation IONOS – Music in the Ether by Maia Urstad, composed for two performers (percussion, voice) and amateur radio operator, and to synthesize these with Jean Baudrillard’s order of simulacra as well as his concept of hyperreality. This is not intended as a critique in the usual sense, but rather as a critical engagement – an attempt to approach a phenomenon objectified in this work.

The sound of radio communication and its semantic connotations

The sound of radio communication, familiar to us from films or computer games and, for some, from professional daily life, is often inevitably associated with an experience of terror. Generally, it recalls catastrophes, whether human-induced or non-human-induced. Three scenarios in which radio communication plays a central role may serve as examples: wars, natural disasters, accidents.

The sound of radio communication is therefore negatively connoted. Few – I am thinking here of infants – can experience it in its mere sonicity; this would require the state of the pre-social. Others may associate it with an amusing activity, the contact with strangers, or as a technical means, for example in coordinating a landing approach. Most often, the medium of radio communication appears as one serving communication in the context of actual or imminent violence – thus also in Urstad’s concert installation.

On the work itself

At the beginning, we hear very quiet, atmospheric synthesizer sounds through the loudspeakers arranged across the three rooms. The spatial-acoustic possibilities of the location are explored, as these sounds appear more perceptiblehere, less there, with dynamics shifting from room to room. The synthesizer sound encompasses the sound of radio communication, which gradually enters, encompasses the static noise arising at the moment of pressing the “communication button” of the radio apparatus, as well as the very softly spoken, thereby de-semanticized radio messages – presumably common codes.

The singer expresses herself for the first time with whistled tones, tonally corresponding to the atmospheric sounds, while the percussionist joins with gentle, rain-imitating sounds. A musical dialogue, which will constitute one of the fundamental principles of the work, is already indicated here, and becomes explicit in the responding sounds of the interacting media – for instance, when suddenly a sample of a raindrop sounds and is immediately reproduced vocally by the singer.

The synthesizer sound clearly asserts the primacy of the composition. It appropriates the “foreign” sounds, absorbs them, and refuses musical dialogue – thus assuming a special position, it remains static, in the Kantian sense a priori. The work exercises these principles (dialogue and refusal) for approximately 40 minutes, during which the sonic and structural predictability of the determined events and forms is disrupted by chance, an irritation – when suddenly at the “end of the line” of the radio operator a voice is heard, the radio operator actually contacts someone who presumably does not assume to be part of a musical work. Indeterminacy opens a liberating moment: the coherent overall sound is broken apart, particularized; something pulls the receiving subject out of the sonically spherical, melancholically appearing sounds of the digital playback and the cries of pain or mourning of the singer, which are simultaneously exhibited, through the percussively produced gentle sounds, as a romantically-nostalgically idealized, completely leveled nature – as part of it, and thus as part of this natural, naive process within digital primacy.

With the persistence, or modified repetition, of the compositional relativization of culturally produced terror, this increasingly presents itself as “normality.” What at the beginning of the work appeared as a violent experience (the cries of pain or mourning of the singer) loses its effect through the normalization caused by repetition; this suffering appears ephemeral and insignificant.

Precisely in the moment of chance, however, the work reveals its underlying ideology. We recognize the actual discrepancy between the “natural,” supposedly justified course of things, and culturally produced terror. The naive, uninvolved voice from nowhere – perhaps an experience of fascination – enables this comparison, provides a glimpse of the apparent “outside” of the composition, and frees us, at least momentarily, from the prior indoctrination – musically and narratively, this constitutes the climax of the work.

The predictable shifts in dynamics and use of the individual rooms, as well as the sonic spectrum anticipated in the opening minutes (full bass; high-frequency cries of pain; cautious percussive elements; soft, spherical sounds), culminate in an expected macrostructure, as the composition gradually dissipates into near silence. Throughout much of the work, its narrative character mostly fails to achieve the intended goal of a tension-rich dramaturgy; the composition remains too fixed in horizontal banality. From the temporal sequence of sound events, little tension arises; a musical turn or a break with the compositional principles is entirely omitted, although precisely after the climax such a rupture could have occurred. An unpredictable eruption in the treatment of verticality, the sonic design, which might have added dramatic tension to this rather pretentious temporal-dramaturgical approach through contradiction, also does not occur – especially since the work, precisely in its predictability, attempts to conceal its own ideology, which, as has been shown, threatens to unmask itself through even the smallest calculated irritation – perhaps through the moment of fascination. Why provoke this?

On the spatial procedure of the work

The tripartition of the venue does not appear arbitrary in view of Edmund Husserl’s three modes of givenness[1] – immediate (immediately given), mediated (mediately given), and merely intended without intuitive content (merely intended). Thus, in one room, percussively imitated sounds of nature present themselves: rustle, rain, or the sound of a woodpecker; in another, vocally produced sounds of culture: speech, singing, cries of lamentation or pain; and in the third, the sound that itself generates hyperreality: the noise-like sound of radio communication, representing an interface between the real and the hyperreal. Furthermore, the atmospherically fluctuating synthesizer sound and the playback samples (for example, the raindrop sample) carried into each room by loudspeakers must also be understood as sounds that generate hyperreality, as they arise from the binary system of code, an immaterial sphere, and at the same time appear either as total abstraction or as an exact duplication of the real, without actual reference to it.

Although we encounter a compositional tripartition, the different sound types are heard as a coherent, homogeneous mass, mediated by the synthesizer sound. This simultaneously raises the question to what extent the first two modes of givenness, in the case of such a work, still allow the real to appear in consciousness, or whether they can only appear in the third mode.

Simulation and Hyperreality

Remarkable is the work-immanent striving for the simulation of the subjective experience of the real, which implies that it is given only in semblance. Thus, in the synthesizer sound, which fills all rooms equally, appropriates the “foreign” sounds, mediates them within itself, and surrounds us homogeneously, we perceive only seemingly the real (the sounds of nature and culture).

We must therefore confront the question of the real and simulation in relation to this work, pursuing whether, in the state of hyperreality, it is still possible to experience the “outside,” the real, and whether the semblance of the subjective experience of the real – the first two modes of givenness, which we find simulatively in the work – are not in fact only semblance-residues of themselves in the hyperreal, and thus are given to consciousness only in the third mode. The thesis is as follows: the alienation from the real has, in this work, progressed so far that the first two modes of givenness can only be simulated in the hyperreal (the exact duplication of the real, which, contrary to mere simulation, stands in no relationship to the real); the first two modes have become altogether obsolete. In short: Baudrillard’s concept of hyperreality and his order of simulacra are objectified in Urstad’s work.

Baudrillard states:

„The end of the spectacle brings with it the collapse of reality into hyperrealism, the meticulous reduplication of the real, […]. Through reproduction from one medium into another the real becomes volatile, it becomes the allegory of death, but it also draws strength from its own destruction, becoming the real for its own sake, a fetishism of the lost object, which is no longer the object representation, but the ecstasy of denegation and its own ritual extermination: the hyperreal.”[2]

Following this thesis, it can be deduced in application to the concert installation: reality dissolves in the duplication of the real in the medium, the musical work, and becomes hyperreality (the real plurality of the first two modes of givenness becomes a plurality existing in empty intention). This is alienated from the real, no longer an object of representation. The term “fetishization” – as understood by Adorno following Marx – expresses complete alienation from an original: neither does the medium, the musical work, stand as a first-order simulacrum, imitation, nor as a second-order simulacrum, production, in any relation to an original, the real (the real is accordingly neither immediately nor mediately perceivable); as a third-order simulacrum, it is purely self-referential (the real can be given exclusively in the mode of empty intention).

In the work, this can be exemplified by the appropriation of purely acoustic sounds, which are mediated by the primacy of the composition, the digital playback, the a priori (the real plurality of first- and second-order simulacra becomes a simulatory/hyperreal plurality). The sounds of the digital playback are those that, as third-order simulacra, arising from the binary system of code, stand in no connection to the real and at the same time, by mediating the purely acoustic sounds, indicate that the work itself generates hyperreality. Likewise, the contact of the media (percussionist, singer) with each other, the compositional principle of imitation and production mediated in the hyperreal, objectifies precisely this self-referentiality of the simulation. Every sound is already based on the a priori code and can only be experienced through it. The hyperreality produced by the concert installation stands in no connection to the real, but “becomes the real itself,” whereby it can appear in all modes of givenness in consciousness.[3]

The real appears to us only simulatively, in semblance-residues, as first-order simulacrum, seemingly originarily or non-originarily given, in the percussive imitation of nature; as second-order simulacrum, seemingly originarily or non-originarily given, in the singer’s production, shaping and distortion; in the sound of the digital playback, as third-order simulacrum, as empty intention, in hyperreality.

At this point, it should be noted that Baudrillard’s order of simulacra and his concept of hyperreality cannot be applied exclusively to Urstad’s work, although this work, due to its sound/sign generation – through the digital playback third-order simulacra arise, the re-/produced, seemingly acoustic sounds (the raindrop), or also the re-/produced synthesizer sound – and the spatial structure, which exposes precisely this differentiated sound/sign generation and the impossibility of escape, is particularly suitable to illustrate the theory. Furthermore, the perspective on hyperreality allows us to understand what exactly the already described climax of the work lets us experience when Baudrillard argues:

„today reality itself is hyperrealist.“[4], further: „So art is everythere, since artifice lies at the heart of reality. So art is dead, since not only is its critical transcendence dead, but reality itself, entirely impregnated by an aesthetic that holds onto its very structurality, has become inseperable from ist image.“[4]

The composition requires that we move through the rooms, as we can also, in a sense, “move” in the hyperreality it simultaneously generates, in order to experience it in all its facets. A subjective experience of the real is simulated within hyperreality, when first- and second-order simulacra (seemingly immediately and mediately given), the sounds of nature and culture, appear encoded, metonymically replaced. The code, however, no longer refers to the real, only to the hyperreal, since the “outside” of the hyperreal exists merely simulatively within the “inside,” thus the code, the metonymic replacement, already refers to the established hyperreal system. The only simulatively generated subjective experience of the real (in Husserl’s sense of the real as immediately or mediately given) is not possible in the state of hyperreality, since the hyperreality is already preorganized. It is therefore only a play of the signs themselves, a programmed calculus. As exactly that, a play of the signs themselves, the liberating moment – possibly an experience of fascination – must be interpreted, when the “outside,” the simulated real, appears through apparent chance, apparent naivety, as part of the fully structured and organized hyperreality, through the work.

That the critical transcendence as an immanent principle of art is dead does not necessarily exclude that it can be simulatively restored with comparable effectiveness, albeit now as an immanent principle of hyperreality, not of art. The experience of fascination, the experience of negativity as the possibility of a new beginning, re-determination – so Christoph Menke might express it – would then also remain in its technically, hyperreal produced form. Baudrillard also notes: „Today, where the real and the imaginary are intermixed in one and the same operational totality, aesthetic fascination reigns supreme:”[6]. Does it – the aesthetic fascination – allow us to penetrate the integral ideological formation of the work, when culturally produced violence, which within the autonomous simulation, the hyperreality, undergoes the process of naturalization, is opposed by a reflexive instance through the simulated real with critical potential? If thats the case, we must surrender ourselves to it in the will of desubjectification.

[1] In this reflection, a conceptual juxtaposition is made between Edmund Husserl’s modes of givenness and Baudrillard’s order of simulacra, as both models illustrate a gradual decline in reference to the real, and this juxtaposition provides the opportunity to analyze a reality mediated through givenness/signs.

Husserl distinguishes that X is given to consciousness immediately, originary; mediated through modes such as memory, imagination, or expectation, non-originary; or merely intended, without intuitive content, as empty intention. Baudrillard describes that signs initially still refer to the real (first order), then are mediated within a system via series or codes (second order), and finally generate hyperreality without any reference to the real (third order).

Computer-generated or manipulated sounds must be understood as third-order simulacra, referring only to the code itself, totally abstracting or exactly duplicating the real.

[2] Jean Baudrillard: Symbolic Exchange and Death. With an Introduction by Mike Gane. Translated by Iain Hamilton Grant. London 1993, p. 97 f.

[3] A paradox becomes evident here, as in the state of hyperreality the real can appear to consciousness exclusively in the third mode of giveness, whereas the hyperreal itself can appear to consciousness across all three modes of givenness.

[4] Baudrillard: Symbolic Exchange and Death., p. 82.

[5] Ibid., p. 83.

[6] Ibid.

Musikalische Simulation und Hyperrealität

In folgender Reflexion möchte ich einzelne Aspekte der Konzertinstallation IONOS – Music in the Ether von Maia Urstad für zwei Performerinnen (Perkussion; Stimme) und Amateurfunker herausarbeiten und diese mit Jean Baudrillards Ordnung der Simulakren sowie seinem Konzept der Hyperrealität zur Synthese führen. Es soll hierbei nicht um eine Kritik im gewöhnlichen Sinn gehen, eher um eine kritische Auseinandersetzung, einen Versuch der Annäherung an ein im vorliegenden Werk objektiviertes Phänomen.

Der Klang des Funks und dessen semantischen Konnotationen

Der Klang des Funks, wir kennen ihn aus Filmen oder Computerspielen, manche vielleicht aus dem Arbeitsalltag, ist oftmals unweigerlich mit einer Wahrnehmung des Schreckens verbunden. So erinnert er uns im Allgemeinen an Katastrophen, menschlich, wie nicht menschlich induzierte. Genannt seien hier zur Exemplifizierung drei Szenarien, in denen der Funk eine zentrale Rolle einnimmt: Kriege, Naturkatastrophen, Unfälle.

Der Klang des Funks ist somit negativ konnotiert. Wenige – ich denke hierbei an Säuglinge – können ihn in seiner bloßen Klanglichkeit erfahren, bedarf es hierfür des Zustands des Vorsozialen; oder ihn lediglich mit einer erheiternden Aktivität, der Kontaktaufnahme mit Unbekannten; oder als Mittel, beispielsweise für die Koordination eines Landeanflugs, assoziieren. Meistens erscheint uns das Medium Funk als eines, welches der Kommunikation im Kontext geschehener oder bevorstehender Gewalt dient – so auch in Urstads Konzertinstallation.

Zum Werk selbst

Zu Beginn hören wir durch eine digitale Zuspielung sehr leise, atmosphärische Synthesizer-Klänge durch die in jedem der drei bespielten Räume angeordneten Lautsprecher. Die räumlich-klanglichen Möglichkeiten der Lokalität selbst werden ausgelotet, wenn diese mal hier, mal dort präsenter erscheinen, in der Dynamik durchaus von Raum zu Raum variieren. Der Synthesizer-Klang umschließt den Klang des Funks, der sich allmählich hinzufügt, umschließt das Rauschen, welches im Moment der Betätigung der „Kommunikationstaste“ der Funk-Apparatur entsteht; oder auch die sehr leise gesprochenen, dadurch entsemantisierten Funksprüche – vermutlich sind es gängige Codes.

Die Sängerin äußert sich erstmals während der Konzertinstallation mit gepfiffenen, den atmosphärischen Klängen tonal entsprechenden Tönen, die Perkussionistin steigt mit sanften, Regen imitierenden Klängen in das musikalische Geschehen mit ein. Ein musikalischer Dialog, der eines der Grundprinzipien des Werks darstellen wird, deutet sich hier bereits an und findet sich explizit in den aufeinander reagierenden Klängen der miteinander in Kontakt tretenden Medien wieder, wenn plötzlich ein Sample eines Regentropfens ertönt und dieses sogleich von der Sängerin vokal reproduziert wird.

Der Synthesizer-Klang stellt merklich das Primat der Komposition dar. Er macht sich die ihm „fremden“ Klänge zu eigen, nimmt sie in sich auf und verweigert sich dem musikalischen Dialog – wodurch er eine gewisse Sonderstellung einnimmt – er ist statisch, im Kant’schen Sinne das Apriorische. Das Werk wird diese Prinzipien (Dialog und Verweigerung) ca. 40 Minuten lang durchexerzieren, wobei sich der klanglichen und strukturellen Erwartbarkeit der determinierten Ereignisse und Formen der Zufall, eine Irritation entgegenstellt, wenn plötzlich am „Ende der Leitung“ des Funkers eine Stimme zu hören ist, der Funker tatsächlich in Kontakt zu jemandem tritt, der vermutlich nicht davon ausgeht, Teil eines musikalischen Werks zu sein. Die Indeterminiertheit eröffnet ein befreiendes Moment, der kohärente Gesamtklang wird aufgebrochen, partikularisiert sich, irgendetwas entreißt das rezipierende Subjekt aus den sphärisch, melancholisch anmutenden Klängen der digitalen Zuspielung und den Schmerzens- oder Trauerschreien der Sängerin, die gleichzeitig durch die perkussiv erzeugten, sanften Klänge einer romantisch-nostalgisch verklärten, vollends nivellierten Natur, als Teil eben dieser und somit als Teil eben dieses natürlichen, unbedarften Prozesses innerhalb des digitalen Primats ausgestellt werden.

Mit dem Andauern, beziehungsweise der modifizierten Repetition der kompositorisch vollzogenen Relativierung des kulturell produzierten Schreckens, erschien uns zuvor eben dies mehr und mehr als „Normalität“. Was sich zu Beginn des Werks noch als gewaltvolle Erfahrung darstellte (die Schmerzens- oder Trauerschreie der Sängerin), verlor all seine Wirkkraft in der durch Repetition bewirkten Normalisierung; ephemer und unbedeutend erschien uns dieses Leid.

Gerade in dem Moment des Zufalls, entlarvt das Werk jedoch seine zugrunde liegende Ideologie. Wir erkennen die eigentliche Diskrepanz zwischen dem „natürlichen“, dadurch gerechtfertigten Gang der Dinge und dem kulturell produzierten Schrecken. Die naive, unbeteiligte Stimme aus dem Nichts – vielleicht ist es die Erfahrung der Faszination, die damit einhergeht – ermöglicht uns diesen Abgleich, gibt uns Sicht auf das scheinbare „Außerhalb“ der Komposition und befreit uns zumindest für einen Augenblick von der vorangegangenen Indoktrination – musikalisch und narrativ ist das der Höhepunkt des Werks.

Der erwartbaren changierenden Dynamik und Bespielung der einzelnen Räume sowie dem sich bereits in den ersten Minuten antizipierenden Klangspektrum (volle Bässe; hochfrequente Schmerzensschreie; vorsichtige perkussive Elemente; weiche, sphärische Klänge), wird sich auch eine erwartbare Großform anschließen, wenn die Komposition sich zum Ende hin wieder im fast Unhörbaren verflüchtigt. In vielen Momenten scheint der narrative Charakter des Werks das angestrebte Ziel einer spannungsreichen Dramaturgie nicht herstellen zu können, zu sehr verbleibt die Komposition in horizontaler Banalität verhaftet. So ergibt sich aus dem zeitlichen Ablauf der Klangereignisse wenig Spannung, auf eine musikalische Wendung oder einen Bruch mit den kompositorischen Prinzipien verzichtet das Werk ganz, wobei gerade dieser nach dem dargelegten Höhepunkt hätte eintreten können. Ein unvorhersehbarer Ausbruch aus dem Umgang mit der Vertikalen, der klanglichen Gestaltung, der diesem recht prätentiösen zeitlich-dramaturgischen Umgang gegebenenfalls eine Dramatik durch den Widerspruch hätte zufügen können, tritt ebenfalls nicht ein, zumal das Werk gerade in der Erwartbarkeit die eigene Ideologie zu verschleiern versucht, die durch – so hat sich gezeigt – die kleinste, wenn auch kalkulierte Irritation – vielleicht das Moment der Faszination – sich selbst zu entlarven droht. Wozu das herausfordern?

Zur räumlichen Verfahrensweise des Werks

Die Dreiteilung des Schauplatzes der Konzertinstallation erscheint uns angesichts der drei Weisen der Gegebenheit[1] nach Edmund Husserl – unmittelbar (originär gegeben), vermittelt (nicht-originär gegeben) und bloß intendiert, ohne anschaulichen Gehalt (als leere Intention) – nicht arbiträr. So präsentieren sich uns in einem Raum perkussiv imitierte Klänge der bloßen Natur: Rauschen, Regen, oder auch der Klang eines Holz-bearbeitenden Vogels, in einem anderen der vokal produzierte Klang der Kultur: Sprache, Gesang und Klage-/Schmerzensschreie und in einem letzten der Klang, der selbst Hyperrealität erzeugt: der geräuschartige Klang des Funks, wobei dieser eine Schnittstelle zwischen dem Realen und dem Hyperrealen darstellt. Außerdem sind da noch der atmosphärisch fluktuierende Synthesizer-Klang sowie der Klang der abgespielten Samples (beispielsweise das Sample des Regentropfens) der digitalen Zuspielung, die durch Lautsprecher in jeden der drei Räume getragen werden. Auch diese müssen als Klänge verstanden werden, die selbst Hyperrealität erzeugen, da sie einerseits dem binären System des Codes, einer immateriellen Sphäre, entstammen und andererseits entweder als totale Abstraktion oder als exakte Verdopplung des Realen, ohne tatsächlichen Verweis auf eben dieses, erscheinen.

Wenngleich wir eine kompositorische Dreiteilung vorfinden, hören wir die differenten Klangtypen doch in ihrer Kohärenz als homogene Masse, einer im Synthesizer-Klang vermittelten Masse, was zugleich die Frage aufwirft, inwiefern die ersten beiden Weisen der Gegebenheit, im Fall eines solchen Werks, das Reale im Bewusstsein erscheinen lassen, beziehungsweise ob dieses nicht ausschließlich in der dritten Weise erscheint.

Simulation und Hyperrealität:

Bemerkenswert ist das werkimmanente Streben der Herstellung einer Simulation der subjektiven Erfahrung des Realen, was zugleich impliziert, dass dieses im Schein gegeben ist. So erscheint uns im Synthesizer-Klang, der alle Räume gleichermaßen einnimmt, sich die ihm „fremden“ Klänge aneignet, diese in sich vermittelt und uns homogen umgibt, lediglich vermeintlich das Reale (die Klänge der Natur und Kultur).

Wir müssen uns in Bezug auf das vorliegende Werk der Frage des Realen und der Simulation stellen, dem nachgehen, ob es im Zustand der Hyperrealität noch möglich ist, das „Außerhalb“, das Reale zu erfahren und, ob der Schein der subjektiven Erfahrung des Realen, die ersten beiden Weisen der Gegebenheit, welche wir im Werk simulativ vorfinden, nicht eigentlich als Schein-Residuen ihrer selbst im Hyperrealen und somit lediglich der dritten Weise dem Bewusstsein gegeben sind. Die These lautet wie folgt: Die Entfremdung vom Realen ist im Fall dieses Werks so weit vorangeschritten, dass die ersten beiden Weisen der Gegebenheit ausschließlich im Hyperrealen (der exakten Verdopplung des Realen die entgegen der bloßen Simulation in keiner Beziehung mehr zum Realen steht) simuliert werden können; die ersten beiden Weisen überhaupt obsolet geworden sind, kurz: dass sich Baudrillards Konzept der Hyperrealität sowie seine Ordnung der Simulakren, in Urstads Werk objektiviert vorfinden lässt.

So heißt es bei Baudrillard:

„Die Realität geht im Hyperrealismus unter, in der exakten Verdoppelung des Realen,[…] und von Medium zu Medium verflüchtigt sich das Reale, es wird zur Allegorie des Todes, aber noch in seiner Zerstörung bestätigt und überhöht es sich: es wird zum Realen schlechthin, Fetischismus des verlorenen Objekts – nicht mehr Objekt der Repräsentation, sondern ekstatische Verleugnung und rituelle Austreibung seiner selbst: hyperreal.“[2]

Folgen wir dieser These, so lässt sich daraus in Anwendung auf die Konzertinstallation Folgendes deduzieren: Die Realität löst sich in der Verdopplung des Realen im Medium, dem musikalischen Werk auf, wird zur Hyperrealität (die reale Pluralität der ersten beiden Weisen der Gegebenheit wird zu einer Pluralität die in der leeren Intention existiert). Diese ist entfremdet vom Realen, kein Objekt der Repräsentation mehr. Der Begriff „Fetischisierung“ – wie auch Adorno ihn nach Marx begreift – drückt die vollkommene Entfremdung von einem Ursprünglichen aus: weder steht das Medium, das musikalische Werk, als Simulakrum erster Ordnung, der Imitation; noch als Simulakrum zweiter Ordnung, der Produktion, in irgendeinem Zusammenhang mit einem Ursprünglichen, dem Realen (das Reale ist dementsprechend weder unmittelbar, noch vermittelt erfahrbar, es ist dem Bewusstsein weder originär, noch nicht-originär gegeben); es ist, als Simulakrum dritter Ordnung, rein selbstreferentiell (das Reale ist ausschließlich in der Weise der leeren Intention gegeben).

Im Werk lässt sich dies anhand der Aneignung der rein akustischen Klänge exemplifizieren, die im Primat der Komposition, den digitalen Zuspielungen, dem Apriorischen, verzehrt werden (die reale Pluralität der Simulakren erster und zweiter Ordnung wird zu einer simulativen/hyperreellen Pluralität). Die Klänge der digitalen Zuspielung sind es, die als Simulakren dritter Ordnung, dem binären System des Codes entstammend, in keiner Verbindung mehr zum Realen stehen und zugleich dadurch, dass sie die rein akustischen Klänge in sich vermitteln, darauf verweisen, dass das Werk selbst eine Hyperrealität erzeugt. Auch vergegenständlicht das In-Kontakt-Treten der Medien untereinander (Perkussionistin, Sängerin), das kompositorische Prinzip der im Hyperrealen vermittelten Imitation und Produktion, eben diese Selbstreferentialität der Simulation. Ein jeder Klang basiert bereits auf dem apriorischen Code, kann nur durch diesen überhaupt entstehen und erfahren werden. Die von der Konzertinstallation erzeugte Hyperrealität steht in keiner Verbindung mehr zum Realen, sondern „wird zum Realen schlechthin“; wodurch sie wiederum in allen Weisen der Gegebenheit im Bewusstsein erscheinen kann.[3]

Das Reale erscheint uns nur mehr simulativ, in Schein-Residuen, als Simulakrum erster Ordnung, scheinbar originär oder nicht-originär gegeben, der perkussiven Imitation der Natur; als Simulakrum zweiter Ordnung, scheinbar originär oder nicht-originär gegeben, der sängerischen Produktion, der Gestaltung und Verzerrung; im Klang der digitalen Zuspielung, dem Simulakrum dritter Ordnung, als leere Intention, in der Hyperrealität.

An dieser Stelle soll angemerkt sein, dass Baudrillards Ordnung der Simulakren sowie sein Konzept der Hyperrealität nicht exklusiv auf Urstads Werk angewendet werden kann, wenngleich sich dieses auf Grund der Klang-/Zeichengenese – durch die digitale Zuspielung entstehen Simulakren dritter Ordnung, die re-/produzierten, scheinbar akustischen Klänge (der Regentropfen), oder auch der re-/produzierte Synthesizer-Klang – und der räumlichen Struktur, die eben diese differente Klang-/Zeichengenese sowie die Unmöglichkeit, sich dem zu entziehen ausstellt, besonders eignet, um die Theorie zu verdeutlichen. Auch ermöglicht der Blick auf das Konzept der Hyperrealität uns, zu verstehen, was genau der oben erläuterte Höhepunkt des Werks uns erfahren lässt, wenn es bei Baudrillard heißt:

„Die Realität selbst ist heute hyperrealistisch“[4], weiter: „Kunst ist daher überall, denn das Künstliche steht im Zentrum der Realität. Die Kunst ist daher tot, nicht nur, weil ihre kritische Transzendenz tot ist, sondern, weil die Realität selbst – vollständig von einer Ästhetik geprägt, die von ihrer eigenen Strukturalität abhängt – mit ihrem eigenen Bild verschmolzen ist.“[5]

Die Komposition fordert ein, dass wir uns durch die Räume bewegen, wie wir uns auch in der Hyperrealität, die sie zugleich erzeugt, gewissermaßen „bewegen“ können, um sie in all ihren Facetten zu erfahren. Eine subjektive Erfahrung des Realen wird innerhalb der Hyperrealität simuliert, wenn die Simulakren erster und zweiter Ordnung (scheinbar originär und nicht-originär gegeben), die Klänge der Natur und Kultur, codiert, metonymisch ersetzt erscheinen. Der Code verweist jedoch nicht mehr auf das Reale, ausschließlich auf das Hyperreale, da das „Außerhalb“ bloß simulativ im „Innerhalb“ besteht, somit der Code, die metonymische Ersetzung, bereits auf das etablierte, hyperreelle System verweist. Die leidglich simulativ hergestellte subjektive Erfahrung des Realen (im Sinne Husserls als unmittelbares oder vermitteltes erscheinen des Realen) ist im Zustand der Hyperrealität nicht möglich, da die diese bereits vororganisiert ist. Die subjektive Erfahrung des Realen ist demnach in diesem Zustand nur mehr ein Spiel der Zeichen selbst, ein programmiertes Kalkül. Als eben das, ein Spiel der Zeichen selbst, muss demnach auch das befreiende Moment – möglicherweise eine Faszinationserfahrung – gedeutet werden, wenn das „Außerhalb“, das simulierte Reale durch den scheinbaren Zufall, die scheinbare Naivität, als Teil der vollends strukturierten und organisierten Hyperrealität, durch das Werk erscheint.

Dass die kritische Transzendenz als kunstimmanentes Prinzip tot ist, schließt gegebenenfalls nicht aus, dass diese nicht simulativ mit einer vergleichbaren Wirkmächtigkeit wieder-/hergestellt werden kann, wenn auch jetzt als immanentes Prinzip der Hyperrealität, nicht der Kunst. Die Faszinationserfahrung, die Erfahrung der Negativität als Möglichkeit des Neu-Anfangens, Neu-Bestimmens – so würde Christoph Menke es vielleicht ausdrücken – bliebe dann auch in ihrer technisch, hyperreell produzierten Form bestehen. So bemerkt auch Baudrillard: „Heute, wo das Reale und das Imaginäre zu einer gemeinsamen Totalität verschmolzen sind, herrscht die ästhetische Faszination überall.“[6] Ermöglicht sie – die ästhetische Faszination – uns das Durchdringen der integralen ideologischen Durchbildung des Werks, wenn der kulturell produzierten Gewalt, die innerhalb der autonomen Simulation, der Hyperrealität, den Prozess der Naturalisierung durchläuft, als reflexive Instanz durch das simulierte Reale ein kritisches Potenzial gegenübergestellt wird? Falls das zutrifft, gilt es diese zu bejahen, sich ihr im Wollen der Desubjektivierung hinzugeben.

[1] In dieser Reflexion wird eine konzeptuelle Gegenüberstellung zwischen Edmund Husserls Weisen der Gegebenheit und Baudrillards Ordnung der Simulakren vorgenommen, da beide Modelle eine graduelle Abnahme des Bezugs zum Realen veranschaulichen und sich durch eben diese Gegenüberstellung die Möglichkeit der Analyse einer durch Gegebenheiten/Zeichen vermittelten Realität ergibt.

Husserl unterscheidet, dass X dem Bewusstsein unmittelbar, originär gegeben ist; durch Modi wie Erinnerung, Vorstellung oder Erwartung vermittelt, nicht-originär gegeben ist; oder bloß intendiert, ohne anschaulichen Gehalt, als leere Intention gegeben ist. Baudrillard beschreibt, dass Zeichen zunächst noch auf das Reale verweisen (erste Ordnung), dann innerhalb eines Systems über Serien oder Codes vermittelt werden (zweite Ordnung) und schließlich ohne Verweis auf das Reale eine Hyperrealität erzeugen (dritte Ordnung).

Als Simulakren dritter Ordnung müssen auch computergenerierte/manipulierte Klänge verstanden werden, die als bloßer Code nur noch auf diesen verweisen, das Reale total abstrahieren oder exakt verdoppeln.

[2] Jean Baudrillard: Der symbolische Tausch und der Tod. Mit einem Essay von Gerd Bergfleth. Übersetztz v. Gerd Bergfleth, Gabriele Ricke, Ronald Voullié. München 1982, S. 113 f.

[3] Es zeigt sich hieran eine Paradoxie, wenn im Zustand der Hyperrealität das Reale dem Bewusstsein ausschließlich in der dritten Weise der Gegebenheit erscheinen kann, wohingegen das Hyperreale selbst dem Bewusstsein über alle drei Weisen der Gegebenheit erscheinen kann.

[4] Baudrillard: Der symbolische Tausch und der Tod., S. 116.

[5] Ebd., S. 119 f.

[6] Ebd., S. 118.