Visite Critique Donaueschingen: Alexander Khubeev

The following text was written in the context of the visite critique during the Next Generation workshop at the Donaueschinger Musiktage 2025.

Having the courage to open the abyss

On Garmonbozia by Alexander Khubeev

A text by Christian Gregori

Approaching a circular stand of twelve sycamore trees surrounding a puddle of thick black substance, we see a father who has just now murdered his daughter, while we listen to an electroacoustic soundscape filled with detuned intervals and muffled screams. It is the beginning of the scene of David Lynch’s cult series Twin Peaks where the concept of “Garmonbozia” will be introduced as materialised human suffering in the form of creamed corn that the evil spirits harvest off the town of Twin Peaks by assaulting and torturing them without them knowing. In typical Lynchian fashion – drawing from his dreams and not fully being conscious of the implications of these – the idea of Garmonbozia is abruptly introduced and never completely explained.

But one would be wrong to categorise this concept of Lynch merely as a nightmarish écriture automatique – the unconscious writing technique of the surrealists. Even if drawn from the unconscious, Twin Peaks is no collage of phantasmagorial dreams. The terror that lies in the dark woods and otherworldy places fascinates us until we slowly understand the phantasmagorial as an authentic scene. Lynch reshapes what he draws from his unconscious into crooked societal study, just as when Walter Benjamin says that the surrealist sphere of images is “the world of universal and integral actualities” (Der Sürrealismus. Die letzte Momentaufnahme der europäischen Intelligenz, 1929)

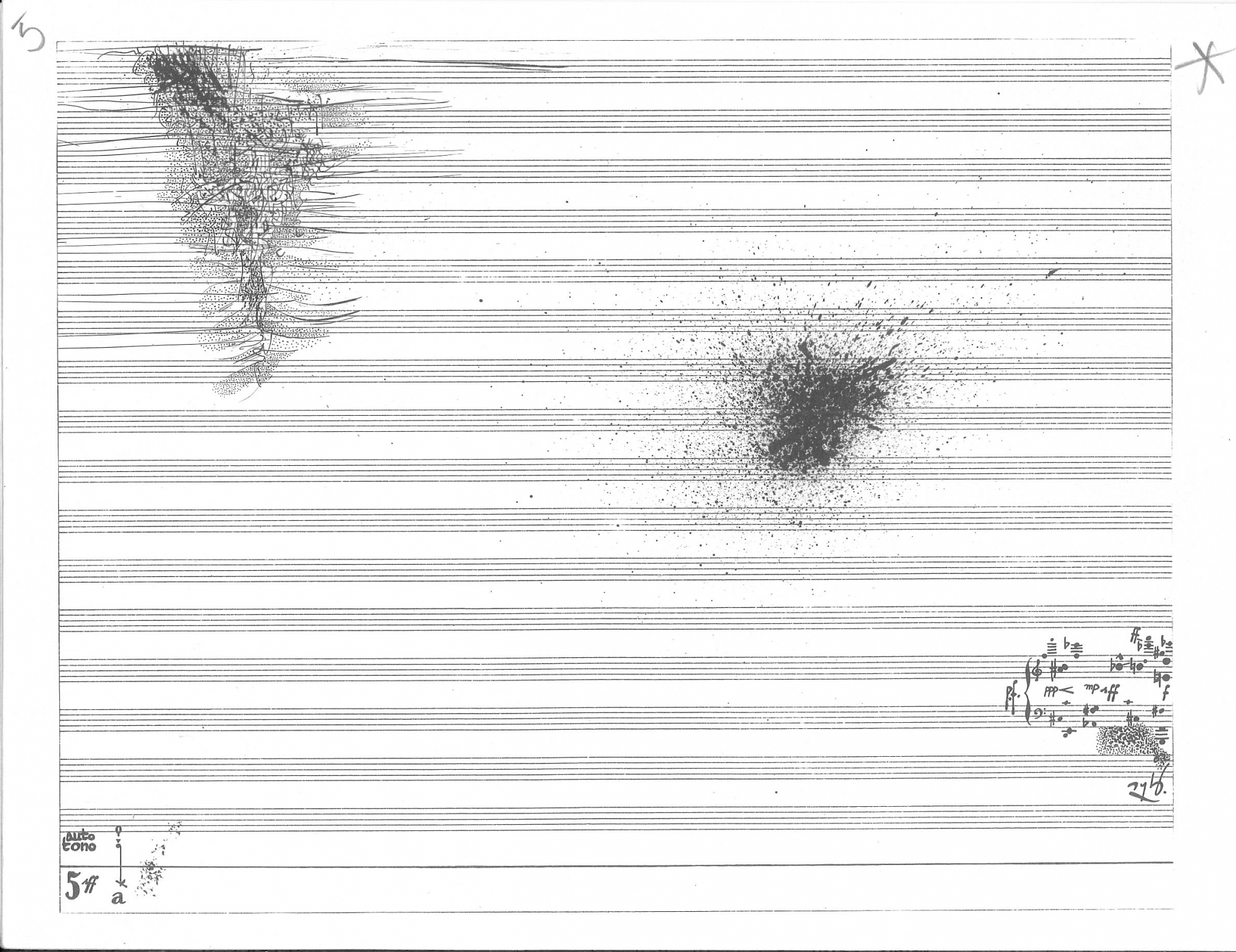

Alexander Khubeev’s ensemble piece Garmonbozia is no programmatic music, insofar as it does not trace any action of Twin Peaks, but it seeks to capture its surreal and terrorising aesthetic quality. The inflicted terror is perceptible even before the first note is played: all instruments are in some way maimed with styrofoam wedged under the strings of the string instruments while the harp is cluttered with papers that snake between the string. Behind them, the woodwinds and brass section have replaced their mouthpieces with boar and bear hunting calls, and the piano is muted with patafix. These mutilations are hidden and will shortly reveal themselves in sound.

Even seventy years after the introduction of prepared instruments, they can still evoke the sense of a violation of the ‘natural’ body of the instrument even though a natural violin is as technically produced and artificial as the styrofoam that blocks its ‘natural’ expression. The prepared sound is perceived as the not-real sound, but, as with surrealist paintings, the longer we listen, the more it asserts itself as more authentic as the ‘natural’, as sur-real, the absolute reality.

Khubeev proceeds to shape two contrasting soundscapes from the sound mass of the ensemble, whose interplay will define the piece with ebbing waves of crescendo and quiet static sections. Soundscape is meant quite literally: as the sonical equivalent of landscape painting of the surreal tradition, like Max Ernst, with its looming terror and disgustingly reshaped nature. The starting crescendo section is dominated by the string section that continuously plays downward-glissandi on the styrofoam-muted strings. They don’t act as a unit – pitches, lengths and rhythmic starting points of the glissandi are disconnected – but they all share a descending motion. Due to the preparation, the resulting collective sound is fluctuating white-noise like but cohesive. The unique movement of every instrument is subsumed by the preparation into a singular soundscape – the mutilation of the preparation kills the ability of the string instruments to display their uniqueness.

This procedure applies to all other instrumental sections as well: both the woodwinds and brass section merge into one mass of multiphonics shaped by the hunting calls while both the harp and piano turn to percussive instruments due to the muting of the preparation. It becomes especially apparent when the harp tries to play cascading arpeggios, but the result is just the ever-same buzzing.

Formally these crescendo sections are superseded by quiet static sections that are dominated by deep brass and texture-focussed percussion. These quiet sections are not at all the opposite of the crescendo section. The dissonant terror of the screeching seagulls remains as an imprint on the space of the static, a shadow looming over to supposed calmness. Here, a clear relation to Lynch’s treatment of the apparent calm in Twin Peaks can be seen. The most horrifying shots of the series are the unmoving frames: pointing up the staircase onto a buzzing ceiling fan, or the traffic light stuck on red on the pitch-black road next to the threatening forest. These scenes are almost always connected to the static buzzing of electricity, that seems to be in connection with the evil spirits and Garmonbozia.

The piece as a whole is a succession of these two contrasting, but similar sections, varied insofar as the treatment of the instruments gradually changes: glissandi are shifted upwards and then into unstructured chaos while the static at times displays pulses, marching rhythms or cluster-like shimmering in the deepest register. After a few iterations of this ebbing up and down, we come to an end with what seems like a figurative and complex violin solo over a decrescendo-ing soundscape. But nothing seemed to have changed. Even after 15 minutes of trying very hard to deal with these mutilations, the styrofoam hinders the pitches to ring through, the violin is able just to produce buzzing dissonant final notes.

Garmonbozia is formally a rather simple piece, recreating the known formula of contemporary music’s wave-like sections, contrary to its seemingly chaotic nature. Chaos could also mean no-structure, no-form or no-relation. But Khubeev seems strongly in control of this chaos, leading it through its wave-like form, directing to an end. It is chaos not as loss of direction but as directional energy.

One question arises, though, from the basic presumption of preparation, the trauma of mutilation and the chaos. The soundscapes themselves work as metaphors and concretise through their preparation how the past, in form of a mutilating preparation of the ‘healthy’ bodies of the instruments, intrudes on the present and deforms all attempts to break out of it. But it treats terror, trauma and chaos as something cohesive. At no point the sections seem to embrace their chaos and threaten the continuation of time. It is trauma contained in the formulaic waves. It is tame, never threatening its own formulaicness. It sees the border of its own chaos and respects it. In surrealist paintings, we feel a threat to our ability to comprehend: it seems that not we are determining art but that art radically redetermines us. The border that keeps us out of the chaos is transcended. An abyss opens and draws us in until we lose ourselves.

True terror and trauma would let the ensemble crumble and enjoy its own opening up to the abyss, opening us up to the joy of de-subjectification. In Garmonbozia the ensemble seems to enjoy its soundscape too much to take this next step into the abyss, where it would threaten its own cohesiveness and thus threaten the audience’s ability to determine it.

But does it have any other choice? Is it possible, in our current time, to find a form of articulation for our trauma that does not reify and curb it into linear waves instead of letting it keep its free chaotic un-form? It is possible to free ourselves from the preparation that make us unable to break out of the ever-same dissonant soundscape?

What would that form that breaks out look like? Would it be a dynamic explosion? Silence? A cadence? Fading out? They all seem kitsch. We would receive it as equally formulaic. Not only are we, mutilated by preparation, unable to express, but we are also unable to give form to something formless. All form seems formulaic and in vain. The simple form shows us just that inability to be formless. We as humans might need to learn first how to have the courage to open up to the abyss before a piece can do it for us.